Gastroenterology (“GI”) practices have been going through a period of consolidation since 2016 when the most recent wave of GI-focused physician practice management (“PPM”) companies started acquiring practices. Currently, there are several large private equity-backed PPM companies operating in the space, and we continue to observe interest in a variety of transaction types and structures. The GI space is attractive for many reasons, including the presence of ancillary services, favorable demographic trends, and recent changes to colorectal cancer screening recommendations. In addition to these industry tailwinds, operators face challenges related to provider shortages, inflation, and complicated relationships with hospitals. This article discusses the outlook for GI practices and related ancillary services, and analyzes transaction activity and industry valuations.

![]() TRANSACTION ACTIVITY AND VALUATIONS

TRANSACTION ACTIVITY AND VALUATIONS

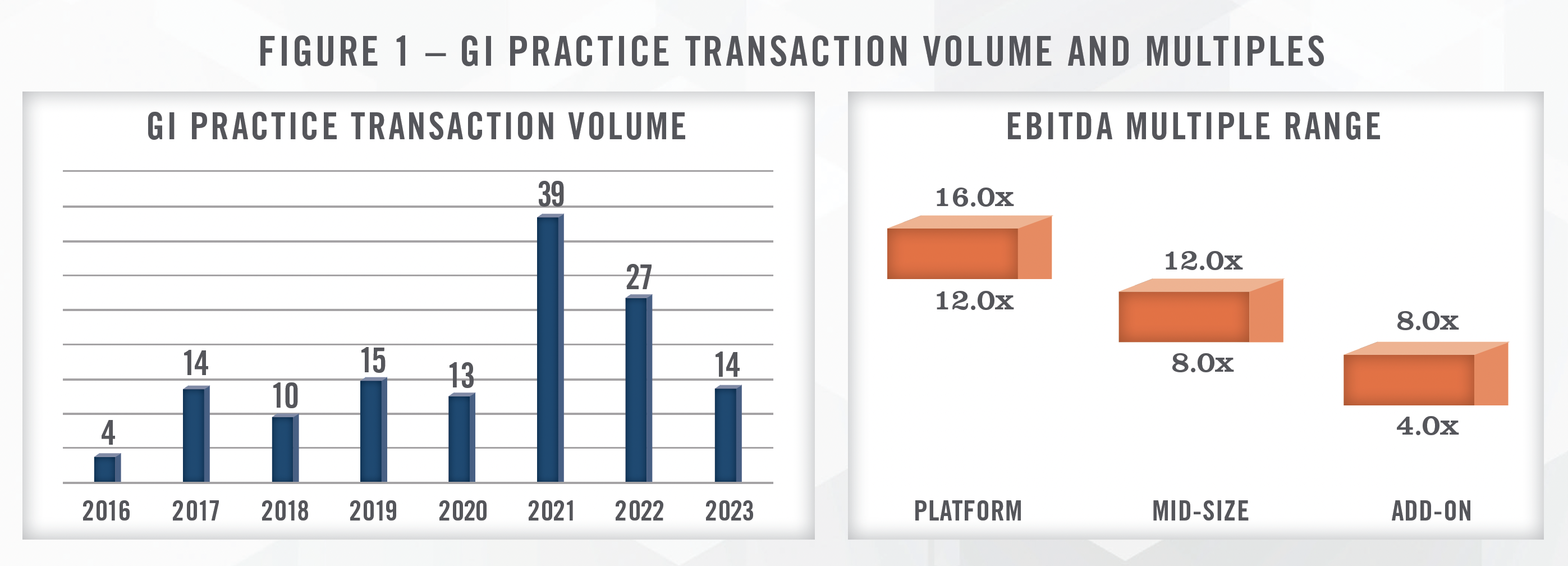

Gastroenterology has been one of the more active specialties for PPM transaction activity in recent years, with several large platforms driving most of the deal volume. The current wave of PPM activity in the GI space started in 2016 when Audax Partners recapitalized Gastro Health. Since that time, there have been more than 130 GI practice acquisitions, with the large GI focused PPMs involved in the majority of those transactions.[1]

As illustrated in Figure 1, transaction volume peaked in 2021, which was an extremely robust year for healthcare M&A. As interest rates started rising in 2022, recession fears creeped in and valuations for healthcare transactions returned to more typical levels. As a result, healthcare M&A, including GI practice transaction volume, has slowed down, although high quality assets continue to transact. The largest platforms in the space account for as much as 90 percent of the transaction volume.[2]

As with all PPM transactions, there is a wide range of valuation multiples paid for GI practices. The valuation multiple depends on a variety of factors, including the size of the practice, location, deployment of technology including high functioning EMR, online booking, referral management, patient engagement, and the presence of ancillaries such as an ambulatory surgical center (“ASC”), diagnostic imaging, weight loss, pathology, infusion, disease management, and anesthesia. We observe midsized GI practice transactions with EBITDA multiples ranging from the high single digits to low double digits. Larger platform acquisition multiples are typically in the mid-teens range, such as the OMERS acquisition of Gastro Health from Audax in 2021 for approximately 16x EBITDA. Smaller tuck-in acquisitions are typically in the mid-single digits range, while GI-focused ambulatory surgery centers have recently transacted in the range of 7x to 9x EBITDA.

“We are currently seeing 10x to 13x EBITDA for practices and 8x to 9x EBITDA for GI focused surgery centers.”

– Large GI PPM Operator

![]() GI PPM PLATFORMS

GI PPM PLATFORMS

There are several large platforms operating in the GI space, including the five largest depicted in Figure 2. Many of the large platforms have transacted in recent years, and our work in the space suggests that there are unlikely to be many additional platforms formed. OMERS acquired Gastro Health from Audax in 2021 with an implied enterprise value of $950 million (approximately 16x EBITDA). GI Alliance is majority owned by physicians, and recently bought out minority investor Waud Capital with financing from Apollo. Kohlberg & Company acquired United Digestive from Frazier Healthcare Partners in March of 2023. In addition to these five organizations that specialize in GI practice operations and related ancillaries, Physicians Endoscopy (“PEGI”) operates an ASC-focused GI strategy that enables physicians to remain independent while investing in GI-specific ambulatory surgery centers. PEGI was originally acquired by Kelso & Company private equity in 2016, and more recently sold to SCA Health (part of UnitedHealth Group subsidiary, Optum) in June of 2022. CRH Medical specializes in providing anesthesia services for GI ASCs and office-based surgery settings and is owned by WELL Health (WELL.TO). At the time of its acquisition by WELL Health, CRH Medical had completed 31 anesthesia acquisitions and provided anesthesia services to 69 ASCs.[3] Based on data from Irving Levin, the median revenue multiple for these acquisitions was 1.5x and the median EBITDA multiple was 3.5x. Most of these transactions involved smaller practices with less than $10 million in revenue.[4] Smaller platforms operating in the space include Gastro Care Partners, Gastro MD, Digestive Capital Care, Allied Digestive Health, and Pinnacle GI Partners.

We note that the number of platforms operating in the GI field is considerably less than other specialties such as ophthalmology and dermatology. Gastroenterology is different from these other specialties in several respects, not the least of which is that GI physicians frequently practice at hospitals in an inpatient setting in addition to their clinical work. This can lead to unique transaction structures and sometimes complicated relationships with hospitals. In addition, several of the platforms have elected to concentrate on gaining scale in a smaller number of regional geographic markets, as opposed to having a national footprint.

![]() TRANSACTION STRUCTURE

TRANSACTION STRUCTURE

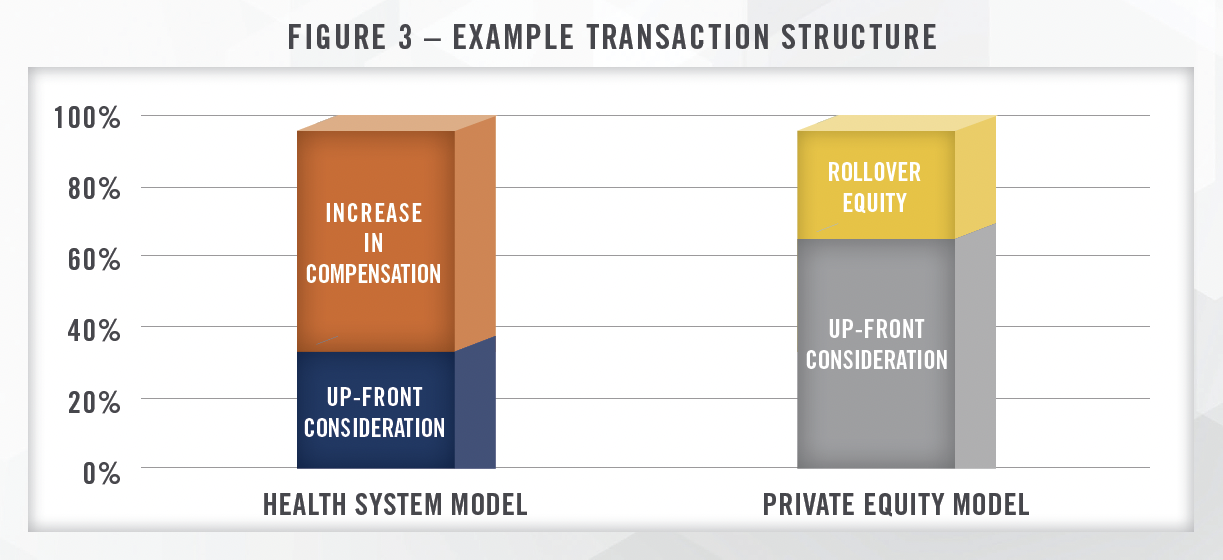

While every practice transaction has unique aspects, there are key fundamental differences between acquisitions by hospitals versus private equity firms. Hospital acquisitions typically are heavily focused on post-transaction compensation, representing a significant portion of the overall value conveyed to the seller. Figure 3 illustrates an example of how value could be allocated for a practice acquired by a hospital, whereby a material portion of the value achieved by the seller is in the form of higher compensation post-transaction. In this example, one-third of the overall value of the transaction would be transferred at closing, with the remaining two-thirds earned over the initial employment term. The amount conveyed through increases in compensation will depend, in large part, on how much compensation the sellers were generating pre-transaction. Given that compensation paid by hospitals and health systems to physicians must be consistent with fair market value, successful GI groups with highly compensated physicians may not be able to realize large pay increases and may require higher upfront purchase consideration.

The private equity model is different from the hospital/health system model in that the sellers typically receive larger consideration upfront, with the remaining consideration rolled over into equity in the platform organization. The amount of rollover equity typically ranges from 20 percent to 40 percent of the total purchase consideration, with recent transactions we have worked on ranging from 30 to 35 percent. In addition, since physician practices typically distribute all available earnings to the owners, EBITDA must be “created” through a reduction in total cash compensation for the sellers (known as a “scrape”). Many private equity transactions are structured such that a large component of the purchase consideration is related to the sale of personal goodwill by the selling physicians.[5] This can have tax implications for the sellers, and we are frequently engaged to value personal goodwill in connection with physician practices selling to private equity platforms.

While many GI practice acquisitions have this structure, we have observed certain unique structures in the space as well. Unlike certain other PPM specialties, which may focus primarily or exclusively on outpatient care, many GI physicians have a substantial portion of their practice in the hospital inpatient setting. Some GI practices are even exclusively hospital based, and many gastroenterologists are employed by hospitals. Particularly for employed physicians, transaction structures tend to be focused on the sale of personal goodwill, since employees do not own any other tangible assets associated with the provision of their medical services. We observe similar “acqui-hire” transaction structures in other specialties, including cardiology and orthopedics, wherein platforms acquire and employ groups of physicians that are embedded within health systems. As discussed earlier, many PPM transactions involve the same acquisition of personal goodwill in addition to other corporate assets, and we are frequently engaged to value personal goodwill in connection with these transactions. For additional detail on these valuations, see our recent article “Personal Goodwill: A Common Multi-Million Dollar Component in Physician Practice Transactions.”

In addition to transactions that are exclusively predicated on personal goodwill sales, we have observed PPM strategies focused on buying the office-based surgery (“OBS”) service line of GI practices. Under these transactions, PPMs acquire the assets associated with the practice’s OBS, and then enter into noncompete arrangements with the practice’s physicians. These strategies often benefit from the site of service differentials between the ASC and OBS, as well as increased case volumes due to certain industry tailwinds. We note that there are different regulatory and accreditation requirements from state to state, as well as different commercial payor reimbursement plans for OBSs. Based on these different dynamics, we observe OBS service lines being more prevalent in certain states compared to others.

![]() ANCILLARY SERVICES

ANCILLARY SERVICES

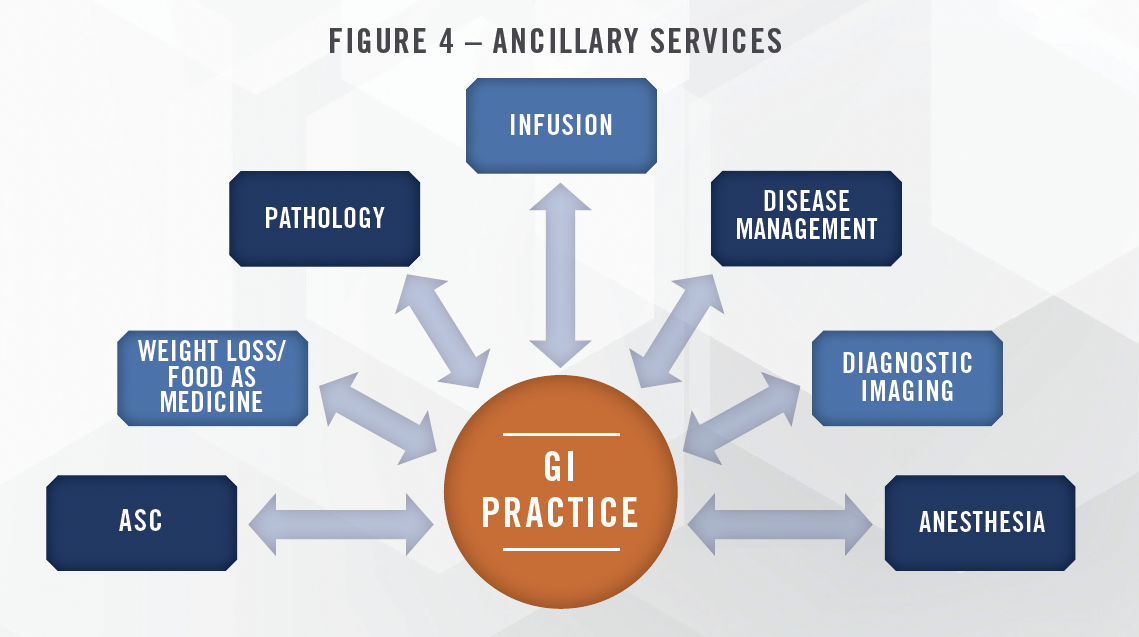

Investor interest in the GI space is driven in part by the presence of ancillary services that can be added or expanded as a practice grows. These ancillary services help drive profitability of a platform, which enables income repair for the physicians post-transaction, and helps a platform reduce the effective multiple paid in practice acquisitions. In our experience, income repair for the physicians is one of the most important aspects of ensuring successful PPM transactions. Figure 4 outlines the various ancillary services that may be provided in conjunction with GI practices.

Many procedures performed by gastroenterologists, including colonoscopies and endoscopies, can be performed in the ambulatory surgery center setting. When billed in the ASC setting, the physician receives a professional fee for the surgical services, and the ASC receives a facility fee. The facility fee revenue can be profitable, and gastroenterologists frequently own equity interests in the ASCs in which they perform cases (whether multi-specialty or single specialty GI-focused centers). As discussed in further detail herein, recent reimbursement trends for the most common GI procedures performed in an ASC have been positive, with the FY2024 proposed rule from CMS including increases of 7 percent to 9 percent, depending on the procedure. Large enough GI practices are able to support single-specialty GI surgery centers that increase the profitability of the platform. Within multi-specialty ASCs, gastroenterology procedures represent a high volume, lower reimbursement procedure that can help keep operating rooms full. In our ASC Survey, we ask multi-specialty centers to rank the desirability of various specialties. While GI usually ranks lower than the highest reimbursing procedures, like orthopedic, spine, and cardiology, it is above the median desirability and ranks higher than many other lower reimbursing specialties. We expect GI ASC volumes to increase in the coming years driven by a number of factors, including the aging population and recent recommendations to lower the age for colorectal cancer screenings.

GI practices can also bring anesthesia services in-house (typically through ownership of a related entity). Billing and collecting for the anesthesia provided to patients undergoing procedures at the practice (in either an office-based setting or ASC) represents a significant revenue opportunity for GI practices. We note that the ability to staff anesthesiologists or certified registered nurse anesthetists (“CRNAs”) represents a significant headwind for the industry and has been pressuring margins in recent years. We continue to see interest in bringing this service in-house to secure reliable coverage and capture the economic benefits associated with providing anesthesia.

Many GI practices offer infusion therapy to patients that suffer from severe or chronic diseases. Certain types of cancers, infections, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and inflammatory bowel disease are examples of diseases that are commonly treated with outpatient infusion services. In addition to infusion services, large GI practices can offer pathology services, which typically involve testing the biopsy samples taken during the procedures. We have observed arrangements wherein the practice bills globally for the pathology services, or bills the technical or professional component only. The ability to provide infusion and/or pathology services can help drive profitability for large practices, but requires investments in space, equipment, staffing, and technology. PPMs provide access to the capital needed to invest in these services, as well as the scale necessary to support profitable service lines. We have also worked with smaller practices that outsource the management of their pathology service line (or other ancillary service line) to management companies that focus exclusively on those ancillary services.

While value-based care (“VBC”) models have yet to gain substantial traction in the GI space, market participants have indicated that certain wellness programs have been well received with payors, and longer-term there are opportunities for GI groups to participate in VBC models that focus on weight loss and disease management, among others. Some market participants also expect that as primary care consolidates, these entities will create narrow networks and need GI groups with scale to refer to, which could benefit the larger GI platforms. As mentioned earlier, several of the larger platforms have focused on gaining density in geographic markets in order to be able to provide these services and participate in value-based care arrangements. Given the prevalence of chronic disease caused by obesity, we believe there are substantial opportunities for GI practices to participate in certain valuebased care models, and we expect the PPMs to push more heavily into this space in the coming years. We note that some digital digestive health startups, including Vivante Health, which raised capital from a group of investors including venture capital funds and Intermountain Health, have raised capital recently, pointing toward continued interest in the space.

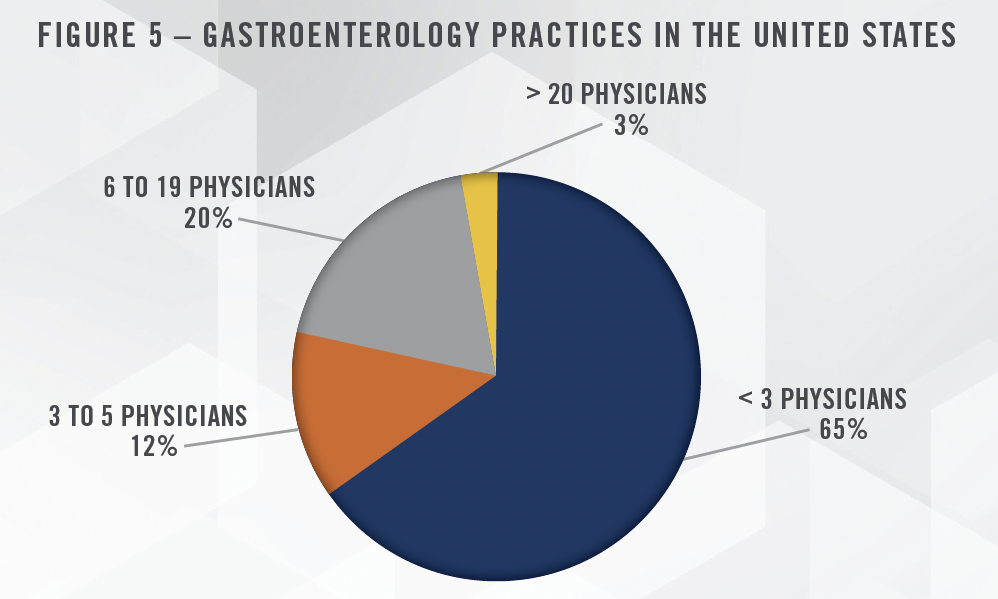

We expect the large GI platforms to continue to consolidate practices, but do not expect many new platforms to form. Approximately 10 percent of GI physicians are currently part of a private equitybacked platform[6], and there is still significant runway for further consolidation. There are approximately 2,100 gastroenterology physician practices in the United States, and the majority of these are small (less than 3 physicians) practices. Given the large number of smaller, independent practices, there remains significant opportunity for further consolidation by the large PPMs. Figure 5 illustrates the size breakout of GI practices in the United States.

![]() INDUSTRY OVERVIEW

INDUSTRY OVERVIEW

The gastroenterology practice industry has numerous tailwinds supporting growth and further consolidation. The aging population and changing guidelines for colorectal cancer screening both represent significant drivers of demand for GI services. The proposed reduction in the 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule conversion factor may result in a reduction to reimbursement for professional GI services if finalized, but proposed increases to facility fees at surgical facilities can help offset such reduction if physicians maintain equity ownership in the facilities where they perform procedures. Longer term, there is a shortage of providers that will impact the ability of the industry to meet the increasing demand, and will make it difficult for practices and platform companies to hire new physicians.

![]() DEMOGRAPHICS

DEMOGRAPHICS

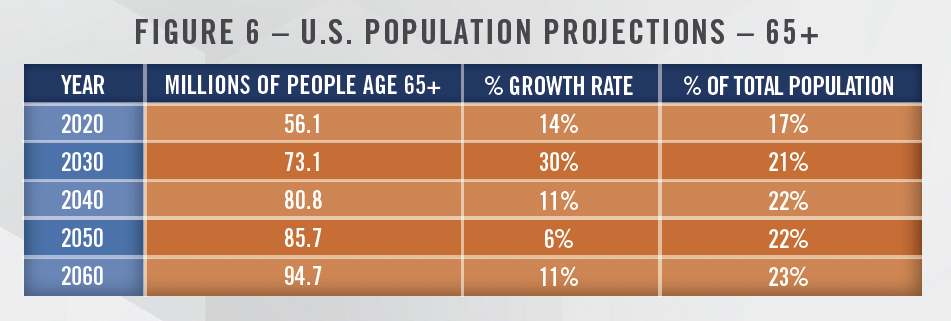

As previously mentioned, the aging population is expected to drive increased demand for healthcare services, with GI services expected to experience a disproportionate increase in demand. Based on population projections from the Census Bureau, the percentage of the population aged 65 and older is expected to increase from 17 percent to 21 percent by 2030, and 23 percent by 2060.[7] As a result, there will be approximately 40 million more Americans over the age of 65. Figure 6 presents demographic projections for the United States.

As the population ages, there is an increased need for common GI procedures, including colonoscopies. In addition, the recommended age for colorectal cancer screenings was recently lowered from 50 to 45, which should lead to millions more screenings. Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death in both men and women, and incidence of these cancers in individuals below the age of 50 has been rising in recent years.[8] As a result, the number of GI screening procedures has increased significantly.

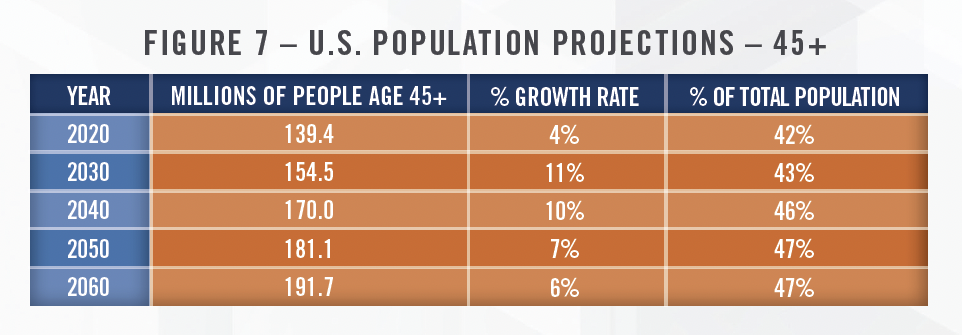

The updated recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force not only increase awareness for people under the age of 50, but likely will make it easier for them to receive a cancer screening without any out-of-pocket cost due to provisions in the Affordable Care Act. This could lead to as many as 15 million[9] additional individuals becoming eligible to receive a cancer screening at no out-of-pocket cost, which should help drive significant growth for GI practices and related surgery centers. Figure 7 presents Census Bureau projections of the population aged 45 and above.

“It is worth noting that GI case growth has been particularly strong so far this year. We see evidence of both deferred care and also expansion of care for the under 50-year-old patient population from recent guideline changes, which we believe should be a source of ongoing and expanding demand over time.”

– Tenet Healthcare Corporation, earnings call with investors on July 31, 2023

![]() REIMBURSEMENT

REIMBURSEMENT

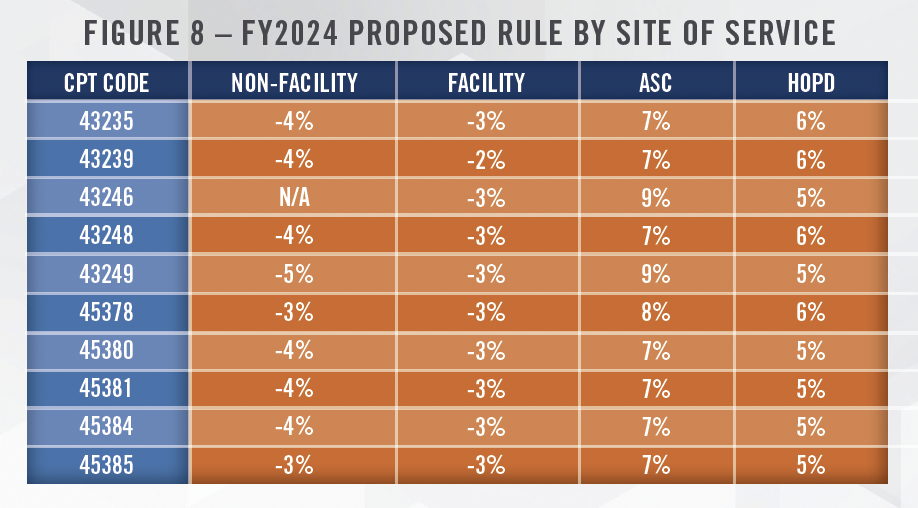

The FY2024 proposed rule from CMS includes reimbursement cuts for gastroenterologists, primarily due to the 3.34 percent reduction in the RVU conversion factor. Figure 8 presents the resulting reimbursement changes under the 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for both facility and nonfacility billing under the proposed rule. As illustrated in Figure 8, physicians performing the top 10 most common GI CPT codes (excluding Evaluation and Management CPT Codes) will experience a reduction in reimbursement from Medicare ranging from 3 percent to 5 percent. Figure 8 also presents the changes in reimbursement for ambulatory surgery centers and hospital outpatient departments. Under the proposed rule, facility fees at ambulatory surgery centers will increase from 7 percent to 9 percent, depending on the CPT Code, while the corresponding increases in reimbursement in hospital outpatient departments will range from 5 percent to 6 percent. The result of these proposed rules is that physicians will receive a reduction in reimbursement for their professional services irrespective of where they perform procedures, but physicians with ownership interests in ASCs will have an offset, while those that perform procedures primarily in an office-based setting face even greater headwinds. This could lead to migration of cases to the ASC setting, which would benefit all PPMs and managers of GI-focused ASCs. It is important to note that these figures are based on the proposed rule, which may differ from the final rule that is typically released in November.

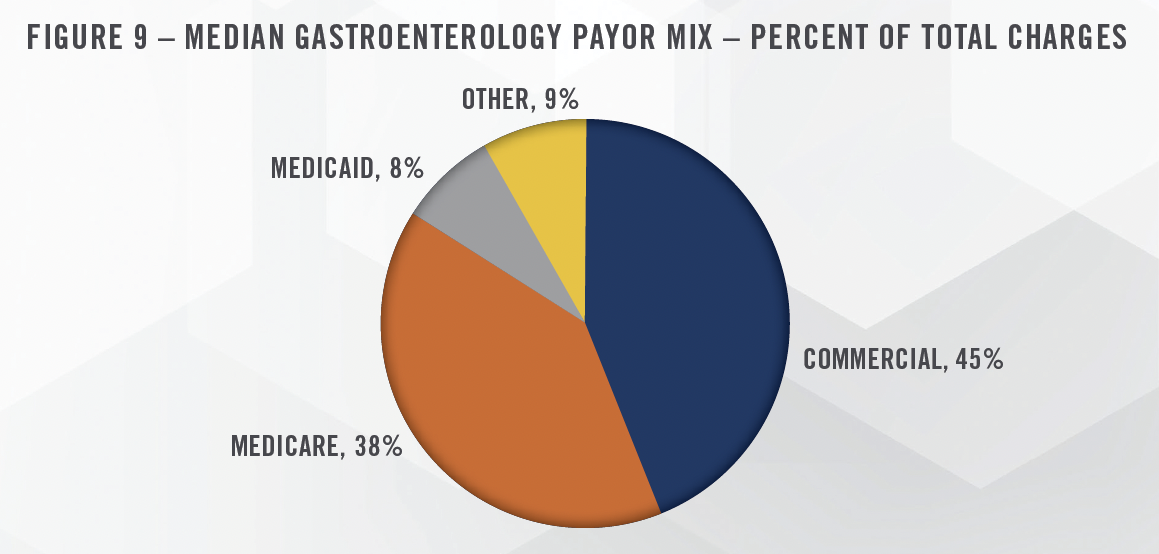

While Medicare reimbursements are certainly important for gastroenterology practices, commercial payors represent approximately 45 percent of practice charges, while Medicare is slightly under 40 percent.[10] Figure 9 presents the median payor mix for gastroenterology practices. According to data from the Urban Institute, the average commercial reimbursement within the gastroenterology space is 120 percent of Medicare.[11] While many specialties generate a higher commercial-to-Medicare percentage, commercial payors are still beneficial to GI practices. We note that the same study found that average anesthesia reimbursements from commercial payors were 330 percent of Medicare, which helps illustrate the opportunity for GI practices that provide their own anesthesia services.

![]() HOSPITAL EMPLOYMENT/CONTRACTING

HOSPITAL EMPLOYMENT/CONTRACTING

As discussed earlier in this article, many GI physicians have a portion of their practice rounding on patients in the emergency department and after admission. Many GI practices also have on-call arrangements with hospitals to cover the needs of emergent patient care. For practices with significant ancillary services and favorable payor mixes (i.e., most PPM affiliated practices), hospital work tends to be less profitable. In our experience, this can present challenges as hospitals still need physicians to round on their patients and provide surgical services. We note that certain other medical specialties, particularly in the hospitalbased physician services space, have seen significant increases in support payments paid to physician staffing companies, and some of the larger staffing companies, including Envision and American Physician Partners, are struggling financially.[12] Given the differences between GI practices and hospital-based physician staffing companies, we do not expect these issues to arise among the GI PPMs. Nevertheless, providing call coverage and providing services under hospital contracts remain an important element of many GI practices, and navigating these relationships represents an ongoing challenge for some practices.

![]() PROVIDER SHORTAGES

PROVIDER SHORTAGES

According to data from CMS, there are more than 14,000 physicians specializing in gastroenterology that are actively involved in patient care in the United States. The Health Resources and Services Administration projects a shortage of more than 1,600 gastroenterologists by 2025[13], with the American Association of Medical Colleges projecting similar shortages relative to demand.[14] The shortage of GI physicians relative to demand is driven by both sides of the supply and demand equation, with demand expected to increase significantly due to the industry tailwinds discussed earlier in this article.

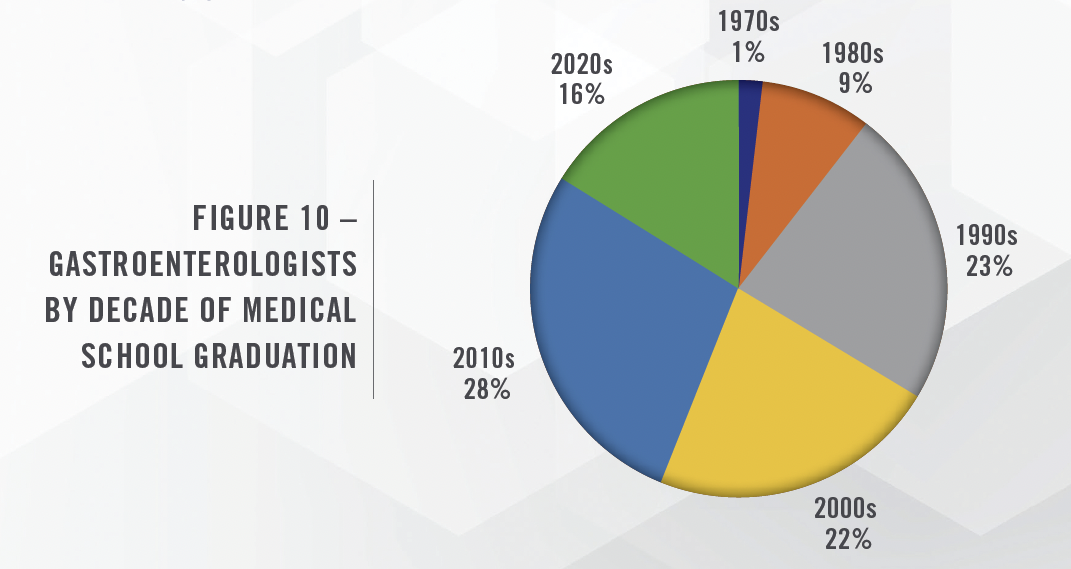

There are also industry concerns about the supply of gastroenterologists based on the current age of the population of GI physicians and the number of physicians currently in medical school. Specifically, approximately one-third of GI physicians currently practicing graduated from medical school in the 1990s or earlier. This suggests a coming wave of retirements that, when coupled with increasing demand, is expected to exacerbate the shortage of gastroenterologists as early as 2025. The projected shortage is not expected to be evenly distributed from a geographic standpoint, with the Northeast region of the United States expected to have a surplus of providers, while the rest of the country is expected to have a deficit. Figure 10 presents the population of gastroenterologists based on the decade they graduated from medical school.

The shortage of GI physicians could have numerous impacts on the industry. Compensation paid to GI physicians will likely increase due to the competition for new providers. This could hurt practice margins as physicians have more leverage to negotiate. With a lack of new providers to recruit, valuation multiples for existing practices should have a relative floor in place, assuming the providers are early or in the middle of their careers. We also expect increasing utilization of advanced practice providers, as we have seen with other PPMs, although there are significant shortages in the nursing space as well. Practices with an acute shortage may experience longer wait times for procedures which can lead to lost revenue. However, increased use of technology should make practices more efficient and reduce the administrative burden on providers.

![]() COMPENSATION TRENDS

COMPENSATION TRENDS

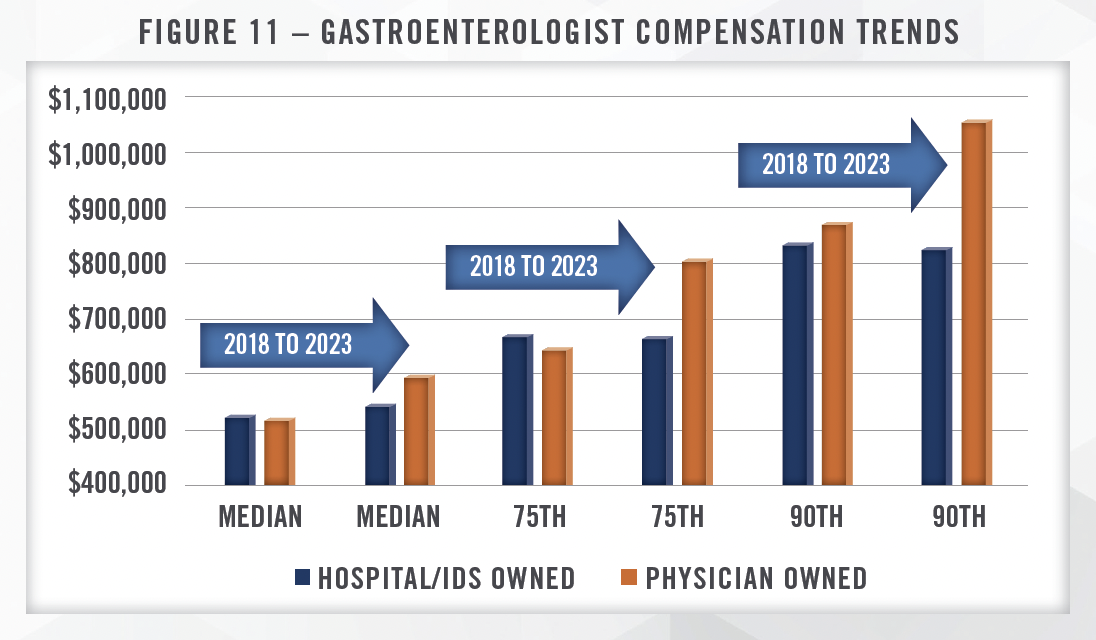

Compensation for gastroenterologists has been increasing in recent years, with diverging trends based on practice ownership. According to data from MGMA, median compensation for all gastroenterologists increased 9 percent from 2018 to 2023, but compensation for hospital owned groups only increased 4 percent, while physician owned groups increased 15 percent over the same time period. These trends are even more pronounced at the 75th and 90th percentile, with hospital owned group compensation actually declining from 2018 to 2023 at both the 75th and 90th percentiles. We note that the hospital owned category includes management services organizations (i.e., PPMs).[15] As discussed earlier, physicians typically take pay reductions as part of PPM transactions, whereas hospital acquisitions of practices often include an increase in compensation. Given the increase in PPM acquisitions over the last several years, this could be a factor driving compensation trends within the industry. As discussed earlier, income repair is a critical factor in successful PPM models, and declining cash compensation does not necessarily equal less income for physicians involved in PPMs.

![]() CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

The GI space should benefit from strong demand for services as long as there is sufficient capacity among providers to meet the growing need. We expect the large PPM platforms to continue to consolidate markets, and we see significant GI opportunities in value-based care over the long term. While the overall healthcare M&A landscape has slowed relative to the activity observed when interest rates were at or near 0 percent, we believe the GI subspecialty is poised for continued transaction activity due to the industry tailwinds and the still relatively fragmented market. Contact the experts at HealthCare Appraisers to discuss your valuation or advisory needs regarding any contemplated activity in the GI space.

![]() Read the other articles in our 2023 Trends and Outlook series:

Read the other articles in our 2023 Trends and Outlook series:

[1] LevinPro HC, Levin Associates, 2023, August, levinassociates.com. We note that the data presented has been sourced from a single transaction database and is not meant to represent total GI transaction volume but serve as a proxy for the increased transaction activity. Many GI transactions are private and may not be publicly disclosed.

[2] Ibid.

[3] CRH Medical; https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/crh-medical-announces-agreement-to-be-acquired-by-well-health-301223713.html; Accessed September 11, 2023

[4] LevinPro HC, Levin Associates, 2023, August, levinassociates.com.

[5] Employed physicians can also take a reduction in post-transaction compensation and receive upfront consideration and rollover equity.

[6] Gastroenterologyandhepatology.net; The Rise of Private Equity in Gastroenterology Practices; Accessed August 29, 2023

[7] Census.gov; https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf?utm_ source=adwords&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI0KTlzviA5gIVCoeGCh0ewgyUEAAYAyAAEgI4_fD_BwE?utm_medium=ppc; Accessed April 18, 2023

[8] JAMA Network.com; https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2779985; Accessed August 29, 2023

[9] PEGI Journal.com; https://www.pegijournal.com/how-the-new-screening-age-will-impact-the-gi-landscape/; Accessed August 29, 2023

[10] MGMA DataDive

[11] Urban.org; https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104945/commercial-health-insurance-markups-over-medicare-prices-forphysician- services-vary-widely-by-specialty.pdf; Accessed August 29, 2023

[12] Beckers.com; https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-physician-relationships/american-physician-partners-to-close.html#:~:text=It%20 is%20a%20portfolio%20company,in%20a%20statement%20to%20Bloomberg.; Accessed September 11, 2023

[13] Health Resources and Services Administration; https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/data-research/internalmedicine- subspecialty-report.pdf; Accessed April 18, 2023

[14] AAMC.org; https://www.aamc.org/media/45976/download; Accessed April 18, 2023

[15] Per the MGMA DataDive Glossary, the “Hospital/IDS Owned” category includes hospitals, integrated health systems or integrated delivery systems, management services organizations, and physician practice management companies.