![]() OVERVIEW & HISTORY

OVERVIEW & HISTORY

A Certificate of Need (“CON”) is a formal permit issued by a state department of health or other state regulatory agency and grants a company or organization the ability to provide specific healthcare services. CON programs started rolling out nationwide starting in the 1970s with the passage of Section 1122 of the Social Security Act, in response to concerns about both the potential oversaturation of the supply of healthcare, as well as the potential to incentivize unneeded hospital care. Among other objectives, CON programs encouraged building of healthcare facilities in rural areas by limiting competition and providing stable revenues and returns on investment. States also have a direct interest in the cost of healthcare services in their jurisdictions via their Medicaid programs.

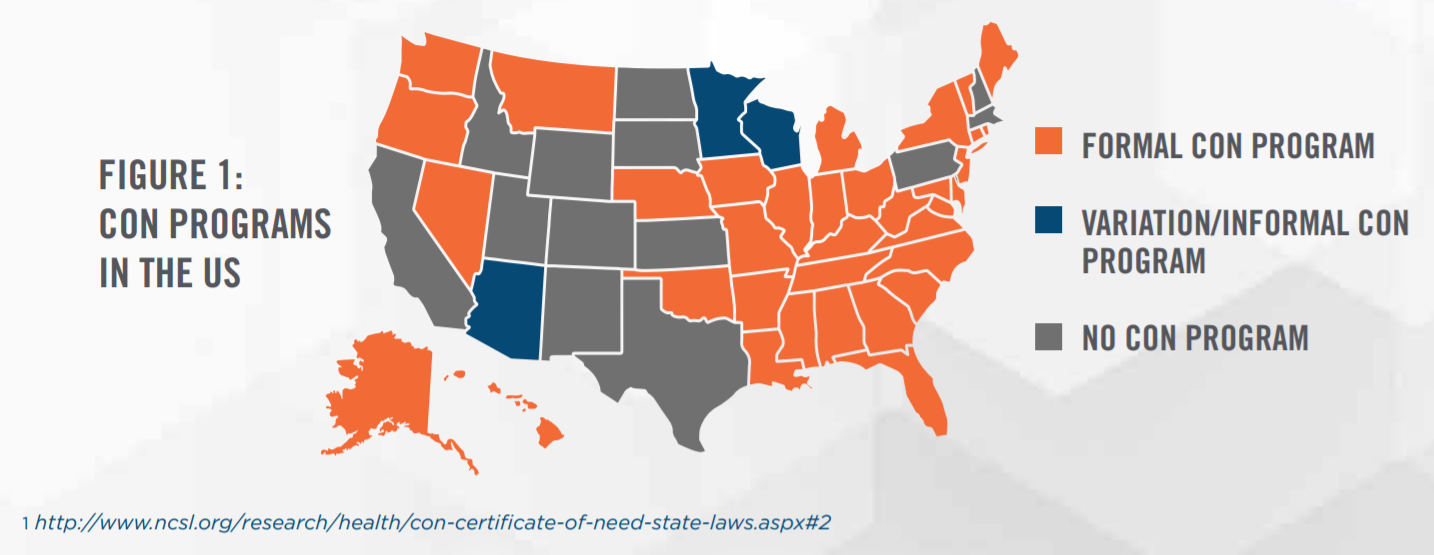

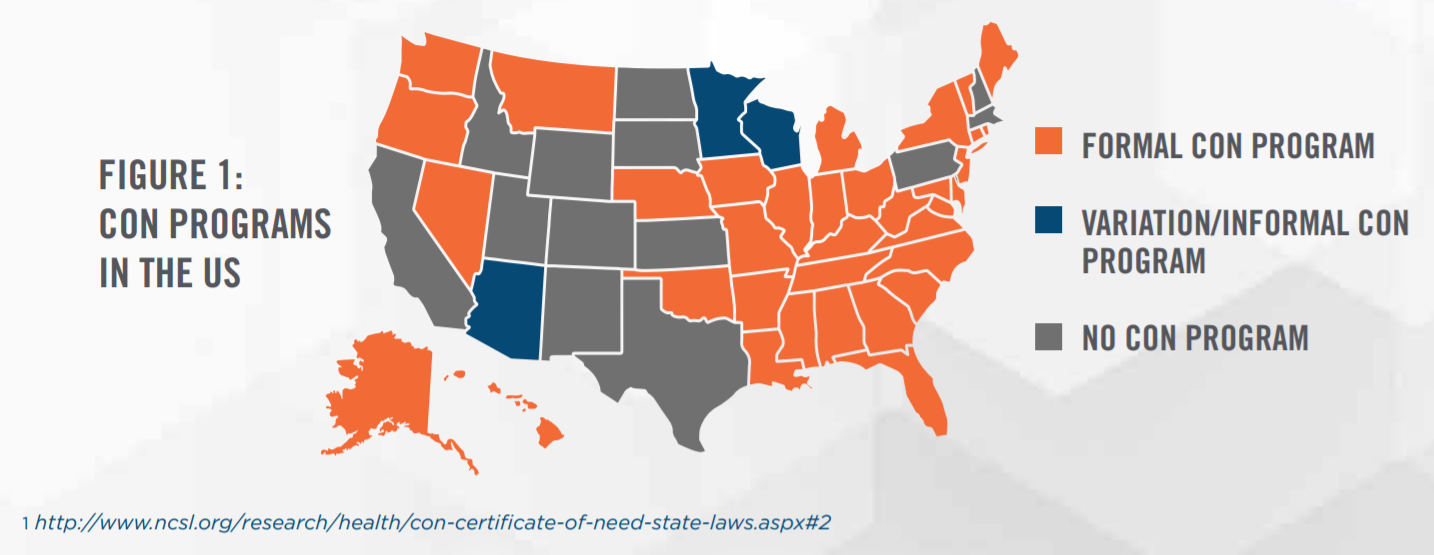

The federal government encouraged states to pass CON laws by making federal funds payable to states contingent on compliance. Every state (except Louisiana) eventually enacted laws to meet this requirement to receive federal funds. The federal mandate and accompanying funds were eliminated in 1987. However, most states still have some version of a CON program. As outlined in Figure 1, 35 states (plus the District of Columbia) have formal CON programs, while 3 other states maintain informal variations of CON programs.[1]

While most states refer to their programs as “Certificate of Need” programs, some states refer to these programs by a different name, such as Louisiana’s “Facility Need Review” and Massachusetts’s “Determination of Need.” Generally, these alternatively-named programs function similarly to CON programs. For simplicity’s sake, we refer to all such programs as CON programs in this article.

With federal incentives eliminated, states are left to their own inclinations, and CON programs vary widely. Typically, CON programs differ on a multitude of factors, including: types of facilities/services requiring a CON; expiration dates; geographic areas covered; circumstances requiring a CON; ability to transfer a few CON; and applicable moratoriums in effect. For example, Nebraska requires CONs only for nursing home, rehabilitation, and long-term care beds, while states such as Iowa utilize a CON program to regulate numerous different types of facilities and service providers and have restricted CON transferability, regardless of whether new services would be provided. Restrictions on CON transferability are observed in a spectrum: some states (albeit few) allow free transfer of the CON as a stand-alone asset; some states require the entire business (i.e., holder of the CON) to be purchased to utilize the CON; and the strictest states prohibit transfers of CONs even when ownership of the holding entity changes. Even the CON application process itself varies across states, with differing time investments and needs assessments required in the application process. When considering the value of a CON, a valuation expert may need to consider numerous possible combinations of factors that apply to a unique set of circumstances.

Currently, the political sentiment surrounding CON programs is divisive. Although some perceive CON programs as a method of limiting the costs of healthcare by documenting a bona fide “need” for healthcare facilities and avoiding situations in which the fixed costs of maintaining empty healthcare facilities inflates healthcare prices, others view these programs as an unnecessary cap on competition for facilities. In April 2017, the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission authored a joint letter to the Alaska State Legislature, which at the time was considering a bill to repeal CON statutes, regarding the anti-competitive nature of CON laws.[2] The letter concluded with a suggestion to repeal CON laws.

Proponents of CON programs counter that delivery of healthcare services typically requires substantial investments and represent critical services to their communities. The vital need for healthcare services requires that such services always be available to the community, and not be subject to the typical ebb and flow of a free market. This is most evident in select urban and rural markets. Finally, CON regulations also provide an outlet through which all stakeholders, from citizens to existing healthcare systems, can provide input.

The fact remains that these programs have survived decades after federal mandates, and we should expect such programs to exist for the foreseeable future. CON programs are not merely relics from decades past—Indiana enacted CON laws as of July 1, 2018, which will replace an existing moratorium.[3]

Possession of a CON effectively creates an economic moat, or a barrier to entry, that provides value as an intangible asset to its holder. How much value is attributable to a CON requires careful, complex analyses of the facts and circumstances regarding the business, the unique market environment surrounding the state’s applicable CON program, and the difficulty in procuring a CON through the normal application process for the subject market.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

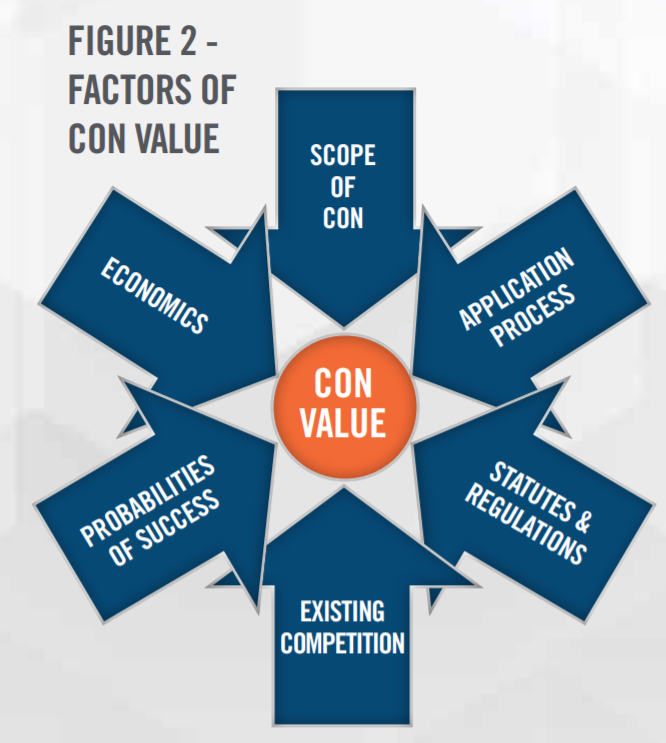

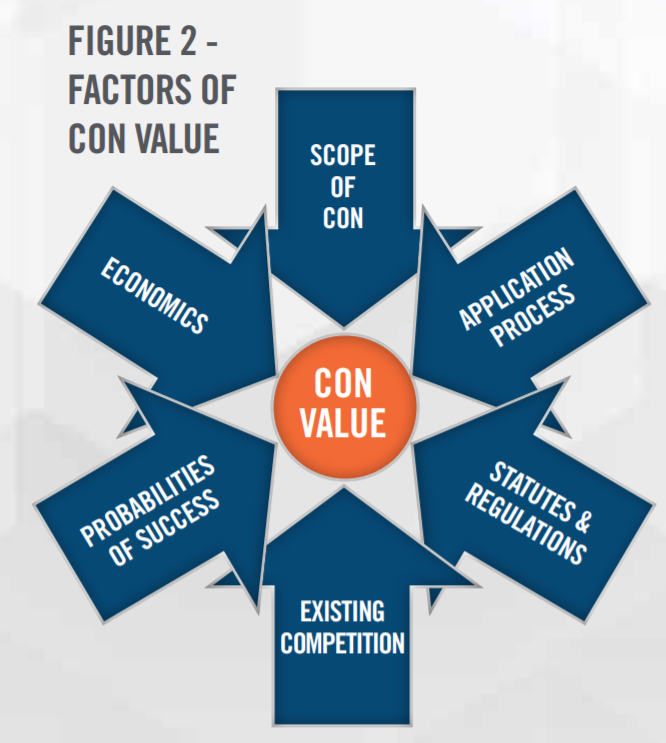

An expert must be able to determine and analyze all factors relevant to the CON itself, the market competition and business environment, the regulatory framework in place regarding the CON activity, and any political factors at hand. Example factors to examine are outlined in Figure 2.

Application Process: Although each state’s application process is unique, they generally share common characteristics of application assembly and need demonstration (specifics vary by state), lengthy review periods (typically 6-12 months), and public commenting periods. The more arduous the application process is, generally the more valuable a CON becomes. At a minimum, the application process requires the work of both high-level management and attorneys, and often other administrative staff. Consultants may be necessary for need demonstration as well. States may have additional determination processes for activities that may not require bona fide CONs, adding additional time to the endeavor.

State Statutes & Regulations: Since each state governs its own CON program, it is important to consider both the established statutes and regulations for the state in question, as well as any pertinent court cases or modifying actions by the state. Although it is important to consider requirements for CONs, it is equally important to review under what circumstances facilities do not require a CON. For example, some states may require ambulatory surgical centers (“ASCs”) to obtain a CON, except in cases where capital expenditures fall under a certain dollar-based threshold or are limited to only a small number of operating rooms. As another example, if a rehabilitation facility does not require a CON to commence a small expansion of its existing facility, the subject’s CON value will differ from a hypothetical identical CON in a state where all such facilities must obtain a new CON to expand. Succinctly put, the viable alternatives to procuring a CON will directly impact the CON’s value. A failure to fully comprehend any strategic alternatives to a desired CON could result in a value which is artificially high. One alternative is to obtain a CON from a company already possessing one. However, the transferability of a CON is not guaranteed, even in cases where an entire entity is being acquired, as mentioned earlier in this article.

Scope of CON: A CON confers the right to perform or provide certain services within a well-defined scope approved by the state. Such scope could include a particular geographic area, or particular subsets of healthcare services. For example, one state may limit an ASC’s CON to provide only Class A surgical services, while another may have no such distinction between Class A and Class C surgical services. The scope of services allowed by the CON may restrict capacity (e.g., number of licensed beds) and a CON that provides for a greater capacity is generally disproportionally more valuable, as fixed costs incurred by a CON holder can be spread over a greater number of capacity units, thereby increasing profit margin. Other common scope considerations include the specialty of medicine practiced, limits on capital expenditures amounts, limitations on ownership of the business holding the CON, and the requirement to serve a limited demographic area.

Some states will also impose unique additional conditions that must be met in order to approve the CON. These conditions may or may not directly impact the holder of the CON. One recently observed example conditionally allowed an ASC to relocate facilities via an approved CON, on the condition that the old facility no longer be used for surgical services. The value attributed to the CON might differ if the subject ASC owned versus leased the former premises. A valuation expert will carefully discern the scope of the CON and conditions for relevant factors in a valuation opinion.

Competition: The current number of market participants will generally inversely correlate to the unmet need for a particular facility or service. If there are many market participants, it is less likely that a new entrant could successfully demonstrate need for the service to obtain a new or expanded CON. Additionally, with a greater number of market participants, there is a greater probability that one of those participants would challenge the new entrant applying for a CON. Such challenges invariably invite high litigation costs and additional resources dedicated to the approval process, all without any guarantee of success. In some markets the expected probability of a CON applicant achieving approval without such a competitor’s challenge could be nearly nil. In such cases, there is scarcely any value in pursuing the application process. Therefore, the fiercer the competition in a market, the higher the value assigned to an existing CON.

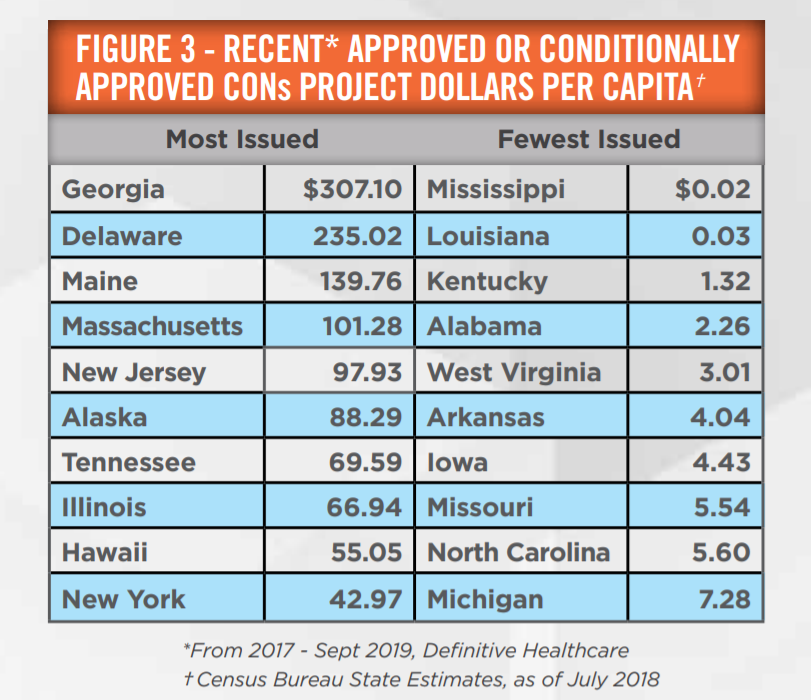

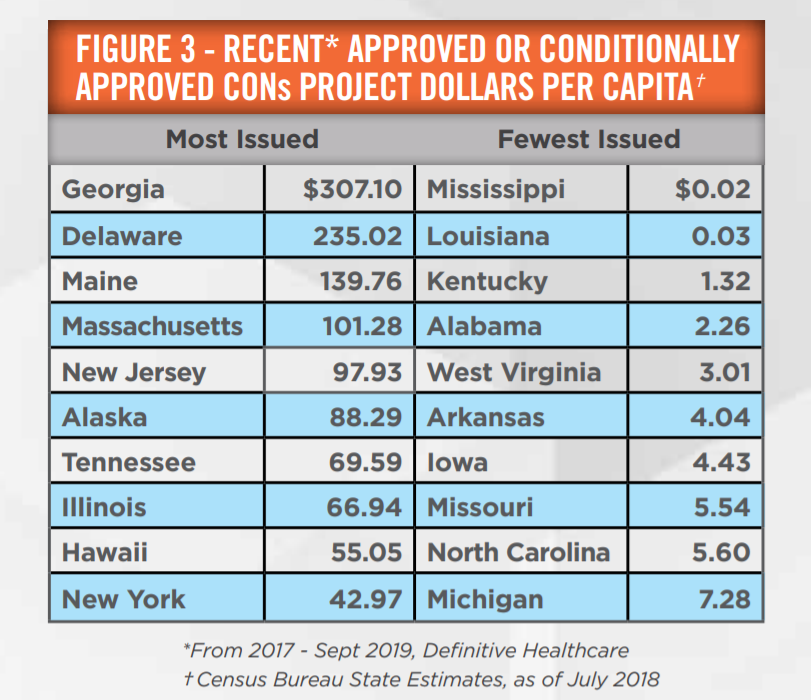

An expert will also examine the occurrence of applicable new CONs within the market. A CON program that continues to issue large numbers of CONs for a service signifies that possession of a CON does not provide much of an economic moat. The barrier to entry is easily bypassed by pursuing the state’s approval process. In recent years, states with high growth in approved CONs include Massachusetts, New York, and Georgia. States with low growth in approved CONs include Arkansas, Michigan, and Mississippi. An expert will evaluate CONs for the particular healthcare service in question. It is quite likely that, in a given state, there are different levels of competition for differing services. HealthCare Appraisers’ experts navigate these variables to evaluate the competitive environment.

Figure 3 outlines the variability in states’ approving new CONs as compared to population. These results are functions of the many factors described in this article. Different states’ statutes may call for many facilities/services to require CONs (e.g., Georgia) or relatively few (e.g., Arkansas). To further illustrate, Mississippi and Louisiana appear on the fewest issued list for different reasons. Louisiana requires few facilities to obtain CONs. In contrast, Mississippi requires a healthy pool of facilities/services to seek CON approval, yet fewer CONs are issued in Mississippi; this is due to political and competitive objections typically raised during the application process, as well as existing market saturation. To add further complexity, some states maintain differing levels of approval, such as Georgia’s “Letter of Non-Reviewability” provision, which outlines criteria which must be met in order to forego the full, traditional CON approval. One observable trend is that states with low CON approval tend to be located in the Southeast region of the US. This may shed insight as to why approximately half of distressed hospital sales have occurred in this region—the relatively low likelihood of a new CON approval helps drive the value proposition of CONs and the ultimate acquisition of these distressed businesses.

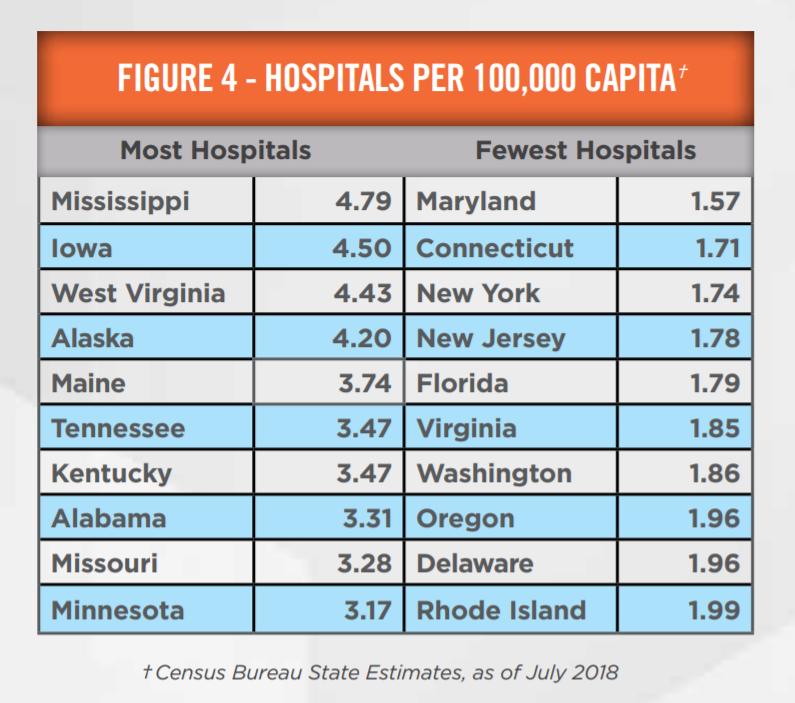

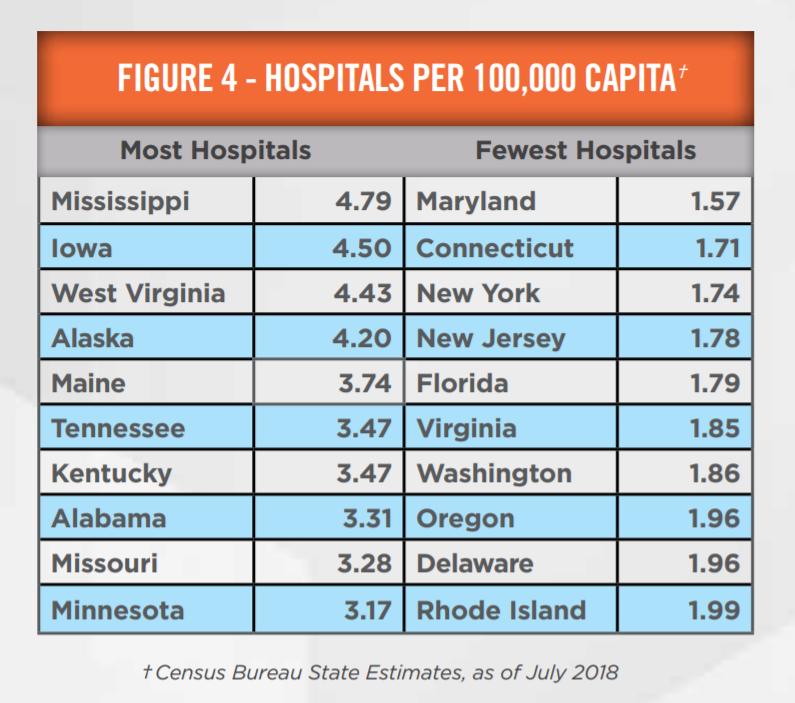

Figure 4 demonstrates the market saturation of hospitals in states where CONs are required for such facilities. This figure outlines all non-government hospitals, (i.e., specialty and general hospitals), but such a rudimentary analysis can provide some insight as to what drives CON approval rates. Mississippi approved very few CONs, as seen in Figure 3. The hospital per capita figures demonstrate that this may be due to market saturation of hospitals, as it has the highest hospital count per capita. Although the two tables are not an apples-to-apples comparison, they suggest that further investigation into relative CON approvals is needed to understand the market dynamics of any given state. One would be mistaken to automatically assume that states with low CON approval rates are therefore highly competitive. Unlike in Figure 3, many of the highest hospital per capita states are not in the Southeast as outlined in Figure 4. This incongruity between Figures 3 and 4 illustrates that experts need to look beyond the surface for additional drivers of a CON market.

Probability of Application Success: Through the state’s approval process, there are many decision points that could potentially result in failure, and therefore, wasted resources. Failure to demonstrate need, outright rejection from the state, or successful challenges waged by the public or competitors can easily render a CON effort moot. A careful analysis of the regulatory framework and market is vital to assessing the probability of success. Related to this factor, an expert will also consider the track record of the state in question regarding CON law. In states with relatively new CON programs or few CONs issued, there is heightened uncertainty with how new issues or litigation challenges may ultimately be resolved. The well-known analogy here is why so many corporations choose Delaware as their home—the courts there have a very long history and have established precedents for how business law is interpreted. Michigan, for example, has a continued history of its CON program since 1972. According to data from Definitive Healthcare, Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services has approved or conditionally approved over 1,000 CONs since 2010. Michigan’s statutes and regulations are well understood. By contrast, Louisiana’s program is relatively new with few CONs approved. Regulations have not been “tested” by courts or the Louisiana Department of Health to the extent that Michigan’s or New York’s have been tested. This presents the potential for unknown risks, and an expert may consider this within a valuation analysis.

Economics: While potentially a wide array of economic characteristics may be considered, an expert will likely review factors such as the expected payor mix and case mix. A CON associated with operations in a less desirable socioeconomic area, with a larger expected Medicaid patient population, will generally yield lower profit margins as compared to an equivalent CON for operations in an area with largely commercially-insured patients.

Additionally, economics may also be considered in some CON approval processes, where demand may be altered by whether the potential patient population can afford the proposed services. This may directly affect whether procuring a CON through standard approval channels is feasible. As an example, in Montana, home health agencies applying for CONs are required to demonstrate that operating such a facility is financially feasible, requiring an accounting of the expected payor mix of the county in question.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

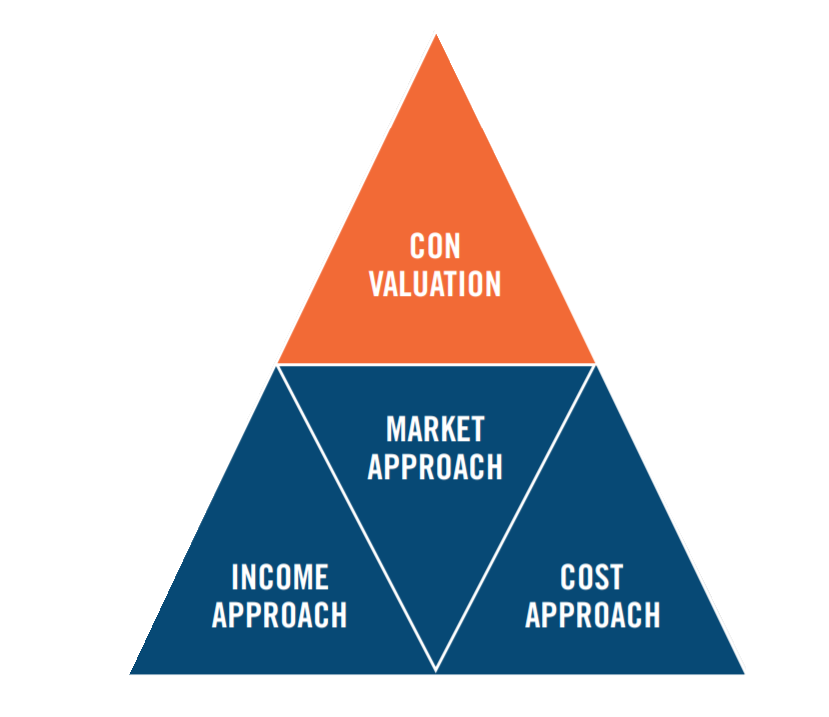

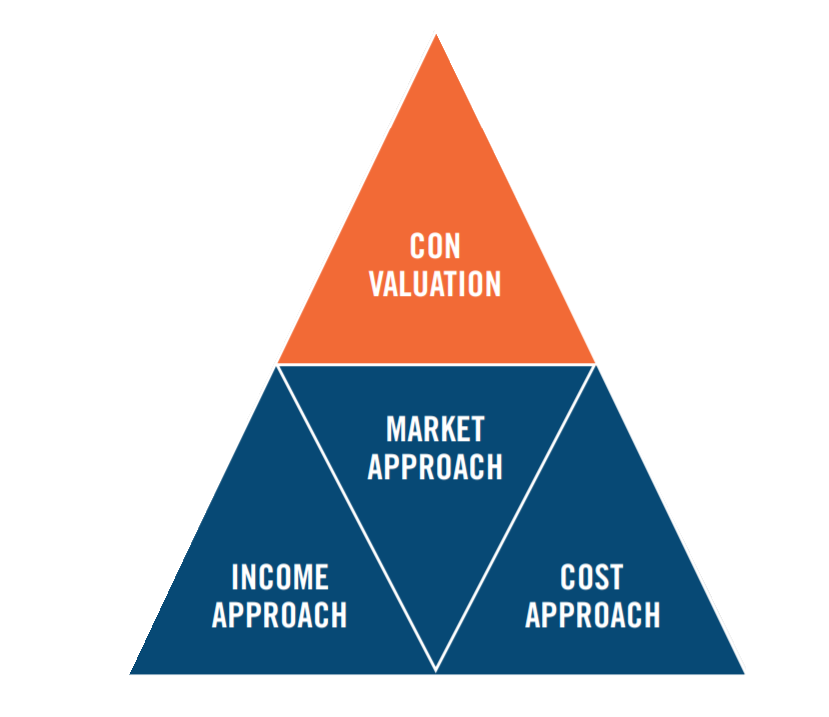

Valuation experts typically consider three approaches in determining the value of a CON: the Income, Market, and Cost Approaches. It may not be required to utilize all three approaches for every CON—the available and determinable facts and circumstances discussed herein will play a crucial role in determining which of the three approaches should be considered in a particular analysis.

Income Approach: The income approach generally attempts to quantify the future economic benefits associated with the CON. The expert must also be certain to exclude a portion of benefits that are realized as a result of other assets used in conjunction with the CON. Methodologies under this approach include the With & Without Method, as well as the Residual Income Method. For the former method, an understanding of the facts and circumstances is applied in two different models. The With Model projects the business’ activities with possession of the CON, while the Without Model projects the activities without possession of a CON at the outset of a projection period. As appropriate, probabilities of success and failure in obtaining the CON may also be taken into consideration. The difference in these two models indicates the value of the subject CON. The Residual Income Method attempts to quantify the value of all intangible assets using assumed rates of return and projected business activity, with a portion of the final value being allocated specifically to the CON. Both of the methods under the income approach rely on quantifying historical and/or future economic benefits associated with a subject CON.

Market Approach: The market approach quantifies the value of the CON based on transactions of other CONs in the marketplace. At this point, there is little need to remind the reader that each CON is quite unique—so finding a suitable comparable, whether transacted or acquired in the marketplace, is a significant challenge. It is harder still to quantify all the variables and qualitative characteristics associated with the CON. Nevertheless, there is still value in considering this approach. Additionally, we note that as part of HealthCare Appraisers’ ASC 2019 Valuation Survey, respondents observed a mode EBITDA multiple premium of approximately 0.51x to 1.00x for ASCs with CONs. In other words, an ASC with EBITDA of $1 million would command an extra $510,000 to $1,000,000 of value over ASCs without CONs. On a final note regarding the market approach, we previously discussed a trend in distressed sales of healthcare facilities; a CON may provide a floor to value in such situations.

Cost Approach: The cost approach attempts to quantify the economic costs associated with obtaining a CON. This approach requires an analysis of the particular market and services for the CON in order to estimate expected costs. Quantitatively, this involves a determination of the time and hourly costs of labor needed for the application, application costs, etc. An analysis of statutes, regulations, and market conditions discussed above will provide additional insight into the challenges of CON procurement.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Assigning a value to a CON may be required as part of a business or asset transaction, a CON being contributed to a joint venture, or for financial reporting purposes. As outlined herein, no two CON valuation matters are exactly the same. A plethora of facts and circumstances, ranging from statutory requirements to market competition, all make each case unique. In all the depth of detail surrounding CONs, one should also be mindful of the Stark Law, Anti-Kickback Statute, and/or Private Inurement considerations which may accompany the transaction. HealthCare Appraisers has helped guide numerous clients in the valuation of their CONs in a variety of jurisdictions. Our thorough approach can be applied to purchase price allocations, fairness opinions, and transaction consulting projects as required.