![]() INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

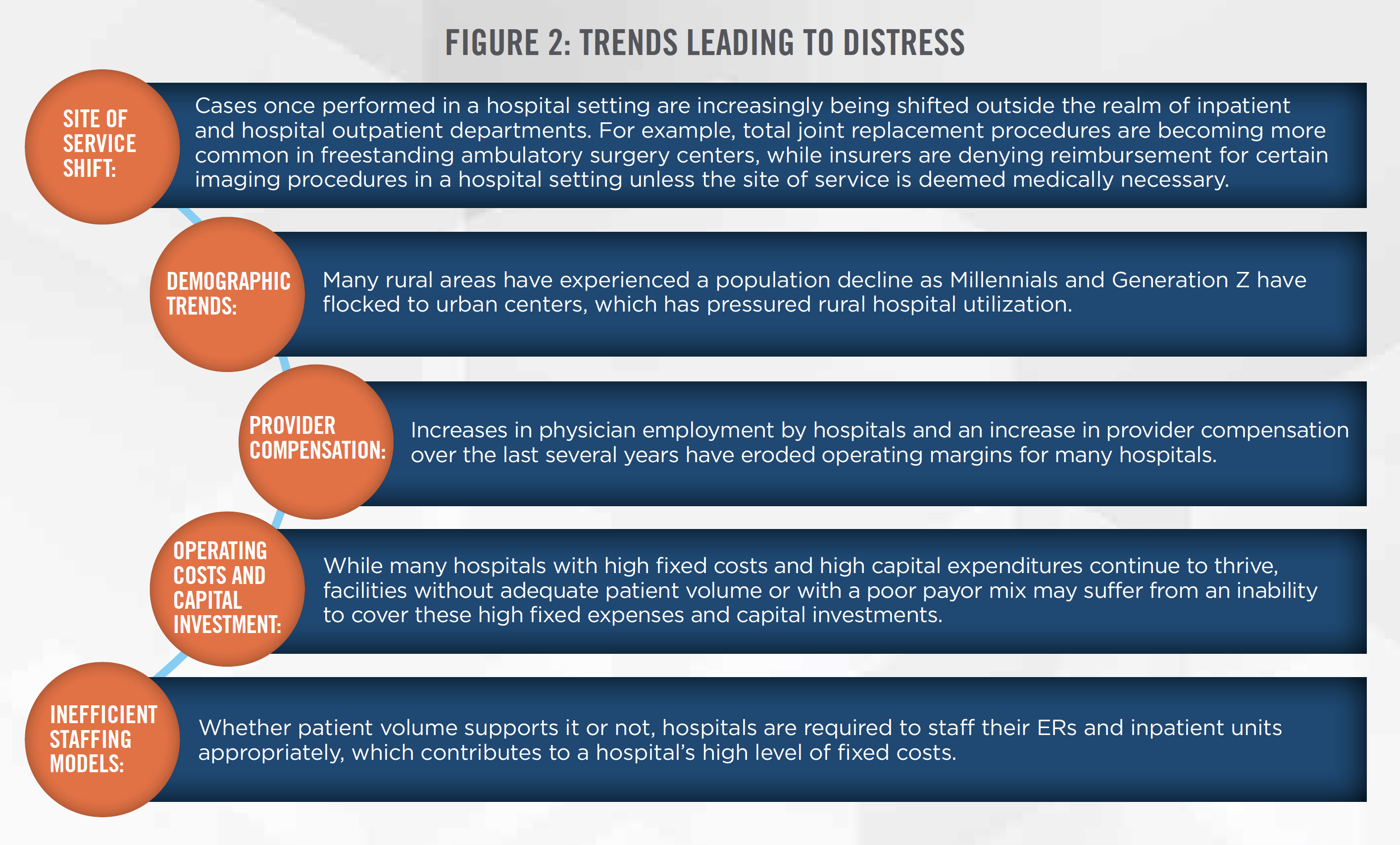

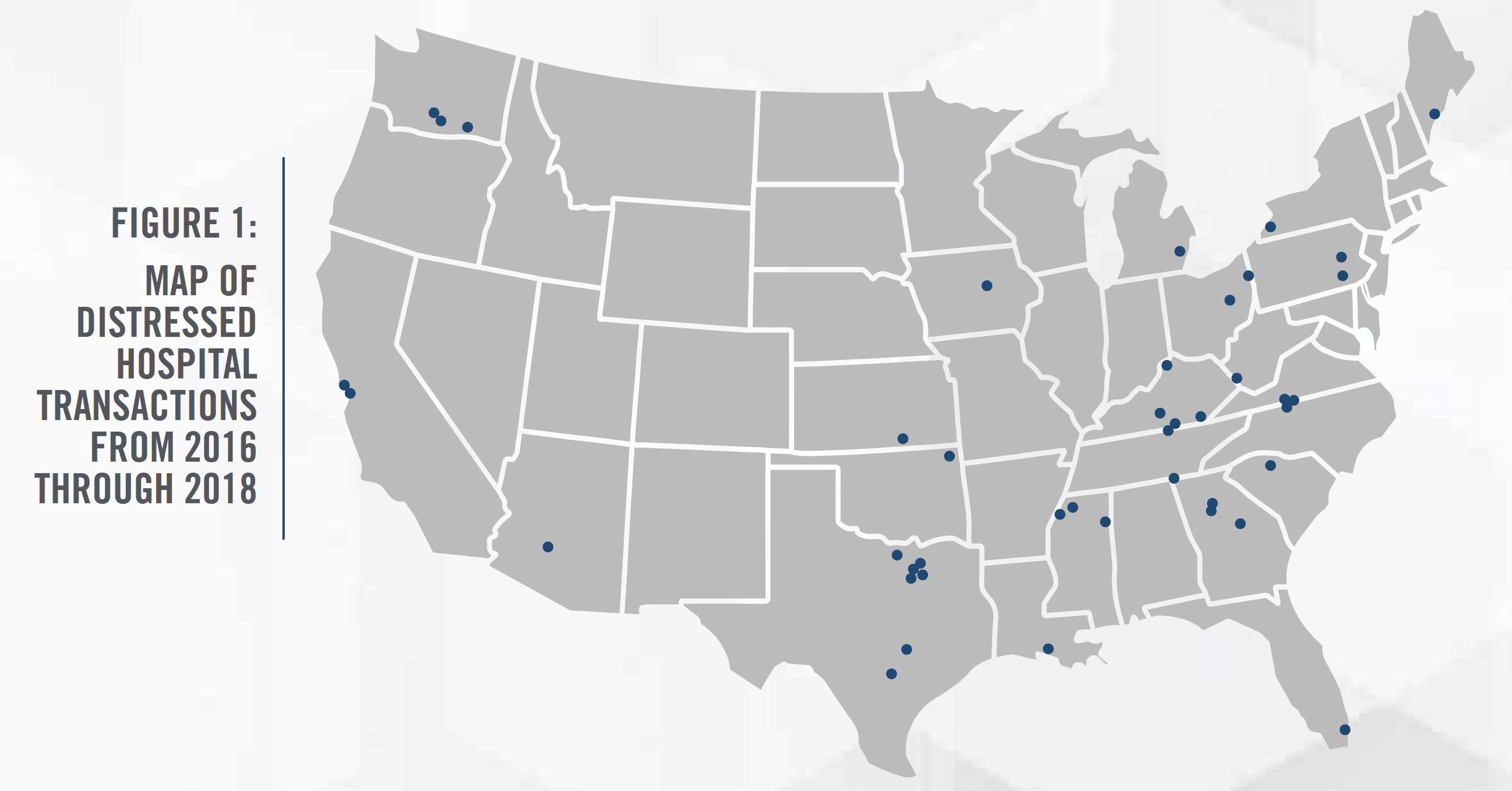

Over the last five years, HealthCare Appraisers has observed an increasing number of hospital transactions involving distressed facilities. Based on our review of hospital transactions reported by the Irving Levin Associates’ merger and acquisition database, distressed hospital transactions accounted for nearly 16 percent of total hospital transactions in 2016. In 2018, distressed hospital transactions represented nearly 27 percent of all hospital transactions.[1] This observed increase in distressed transactions is largely attributed to large hospital operators’ continued efforts to divest underperforming, rural hospitals. Figure 1 provides a geographical representation of over 40 transactions involving distressed hospitals between 2016 and 2018.[2] While the transactions reported in the Irving Levin Associates’ database are not representative of the market as a whole, we believe the trends observed in the database to be reflective of the overall market.

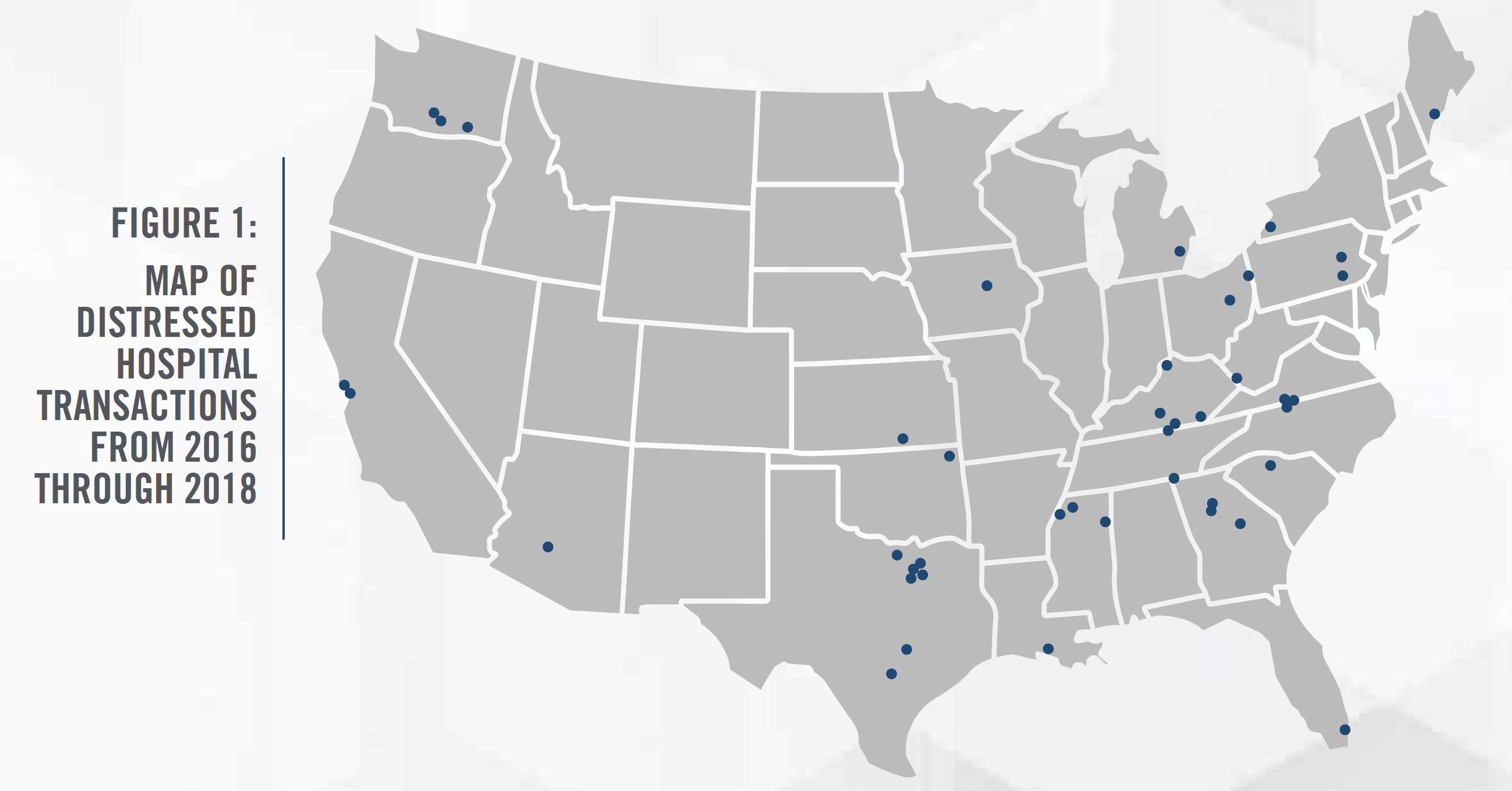

In-line with the aforementioned trend, news of hospitals filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy continue to present in the media, as hospitals attempt to reorganize in hopes of reemerging as more financially stable organizations. At the same time, HealthCare Appraisers continues to provide consultation for healthcare systems selling rural, financially unstable facilities in an effort to shift their resources to more viable urban areas that provide the opportunity for healthy, sustainable growth. Through this work, we have identified the most prominent trends that we believe may lead hospitals into a state of financial distress, as detailed in Figure 2.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

While publications on the latest distressed hospital transactions are widely available, HealthCare Appraisers has observed that many of these publications fail to define what qualifies a hospital as “distressed.” For purposes of this article, we define a distressed hospital as follows:

A hospital reporting multiple, continuous periods of negligible earnings or net losses, which leads to an inability to cover operating costs and necessary long-term capital investments.

Based on an understanding of key financial metrics, such as EBIT margin, EBITDA-to-Debt, EBIT-to-Interest Expense, and Debt-to-Equity, experienced healthcare valuators are able to determine the likelihood that a hospital will be able to continue operations into the foreseeable future (i.e., determining if the hospital or health system is a going concern). Poor measures of liquidity, the inability to cover annual interest expense, and poor EBIT margin are all indicators of financial distress.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Many of the distressed hospitals we have observed in recent years have been located in rural areas. These hospitals have typically experienced several of the trends outlined previously that lead to financial distress. As these hospitals are naturally more susceptible to financial distress, the designation of Critical Access Hospital (“CAH”) is assigned to eligible rural hospitals in an attempt to maintain and improve access to healthcare in rural communities, while reducing risk of financial instability for these designated facilities. Additionally, to provide additional financial support to CAHs, Medicare reimburses such facilities 101 percent[3] of their reported costs for outpatient and inpatient services. The enhanced Medicare reimbursement available to a CAH can be the difference between a profitable hospital and closure.

CAH designations can also assist rural hospitals in qualifying for Medicare disproportionate share hospital payments (“DSH Payments”). DSH Payments are typically made to hospitals serving a large population of low-income patients, compensating hospitals for the costs it is otherwise unable to cover.[4] As a provision of the Affordable Care Act (the “ACA”), DSH Payments were to be phased out with the implementation of federal DSH allotment reductions. The idea behind such cuts was that increases in insurance coverage under the ACA would lead to a decrease in hospitals’ uncompensated care. While Congress has prolonged these cuts from occurring, DSH payments are now expected to begin phasing out in December 2020, and hospitals must prepare for the financial uncertainty that will accompany these cuts in funding should Congress not intervene. The phase out of DSH payments were previously expected to begin in May of 2020, but was pushed back to December as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (“CARES Act”), further discussed in the following section. While CAH designations are intended to decrease the risk of financial instability, CAHs continue to struggle in today’s healthcare environment. A May 2019 study completed by the Flex Monitoring Team, a team of researchers in place to monitor the impact of the Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Grant Program, found that 80.9 percent of the 1,254 CAHs investigated exhibited a moderate to high level of risk for financial distress.[5]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

While the long-term effects of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the operations of hospitals are unknown at this time, initial indications are that the virus will have a significant negative impact on the financial performance of hospitals, at least in the short term. On March 18, 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS”) announced “that all elective surgeries, non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures be delayed during the Novel Coronavirus outbreak.”[6] While hospitals will likely be full of patients suffering from COVID-19 diagnoses, it is the higher margin elective procedures that maintain the profitability of most hospitals. This is highlighted in an example outlined by John Fox – CEO of Beaumont Health, an 8-hospital system with 3,400 beds and $5 billion in annual revenue – in an Opinion piece published by the Detroit Free Press on March 22, 2020. Mr. Fox indicates that his system’s shift away from high revenue surgical and related procedures to medical inpatients with acute complications associated with COVID-19 will result in Beaumont Health experiencing a decline in revenue of $1 billion to $2 billion, which cannot be absorbed by the system’s 4 percent operating margin and cash reserves. In another example, in the March 23, 2020 issue of the Post Bulletin, it was reported that the Mayo Clinic CEO sent a letter to its 63,000 employees indicating that the system was committed to paying its workers through April 28, despite expecting “to see a marked decrease in outpatient surgery volumes in the weeks ahead.”[7] Without federal intervention, these examples are poised to occur throughout many hospitals and healthcare systems throughout the nation, and is highlighted by Moody’s cutting its outlook for nonprofit hospitals from stable to negative in March of 2020 as COVID-19 cases continued to rise in the United States.

While the shift from higher margin elective procedures to lower margin, resource intensive COVID-19 patients will have the most pressing impact on hospitals’ operations and cash flows, it is not the only issue hospitals and health systems will be facing in dealing with the pandemic. A nationwide shortage of surgical masks and other personal protective equipment, ventilators, and even nurses, may result in higher prices for those hospitals looking to procure such resources to deal with the expected patient influx, putting additional pressures on operating margins. Depending on the long-term impact of the pandemic and the current financial state of a given hospital, certain hospitals may find their operating margins and cash onhand is not enough to weather the pandemic. This may result in a substantial increase in the number of distressed hospitals throughout the country.

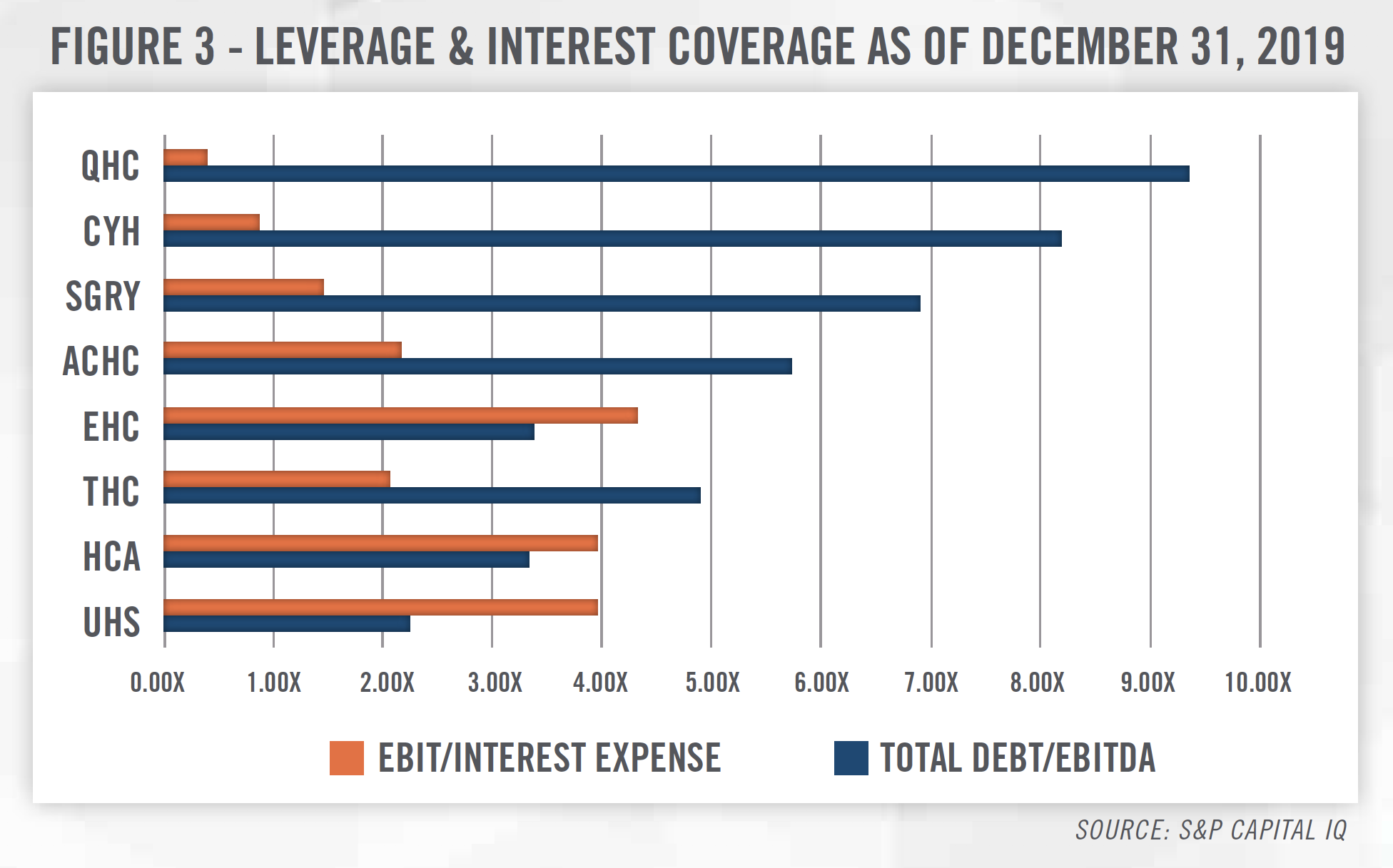

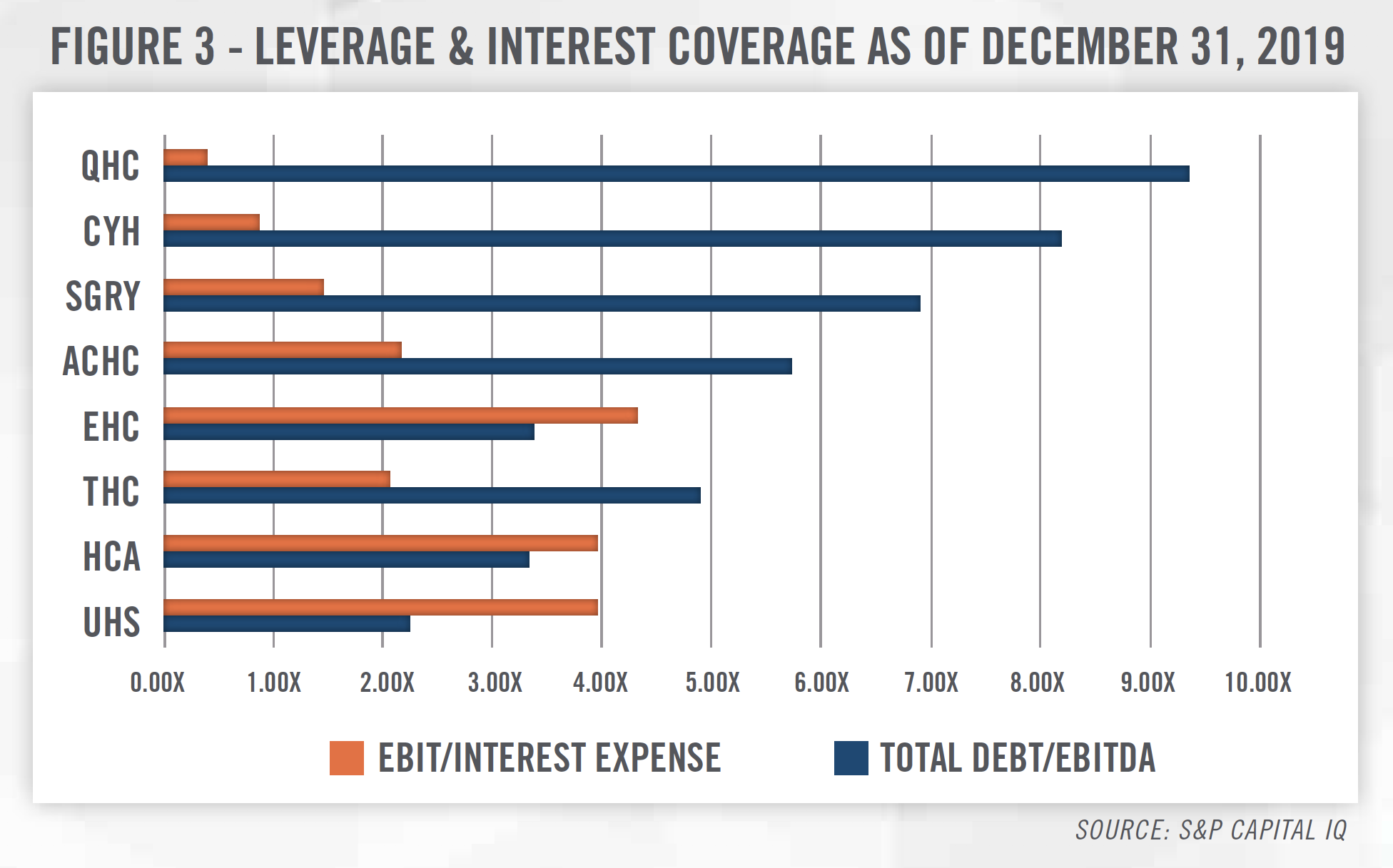

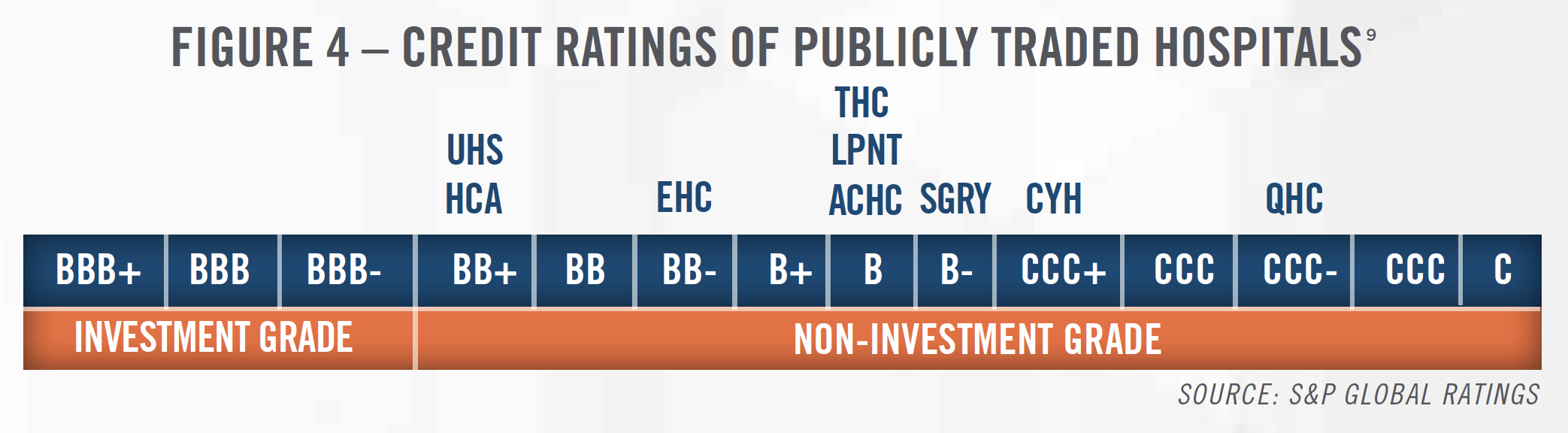

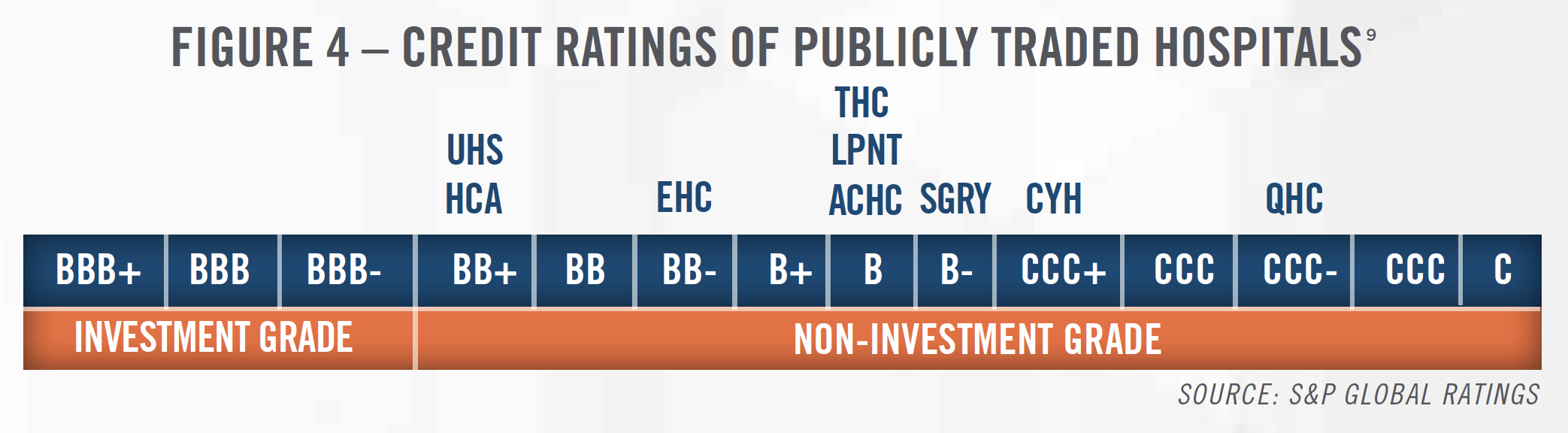

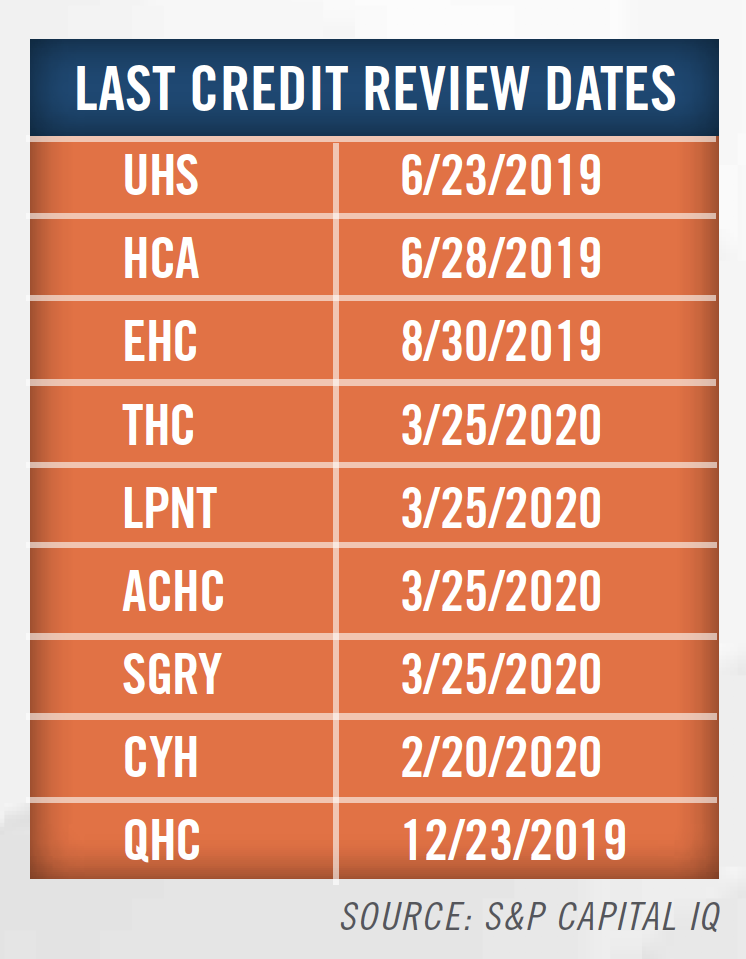

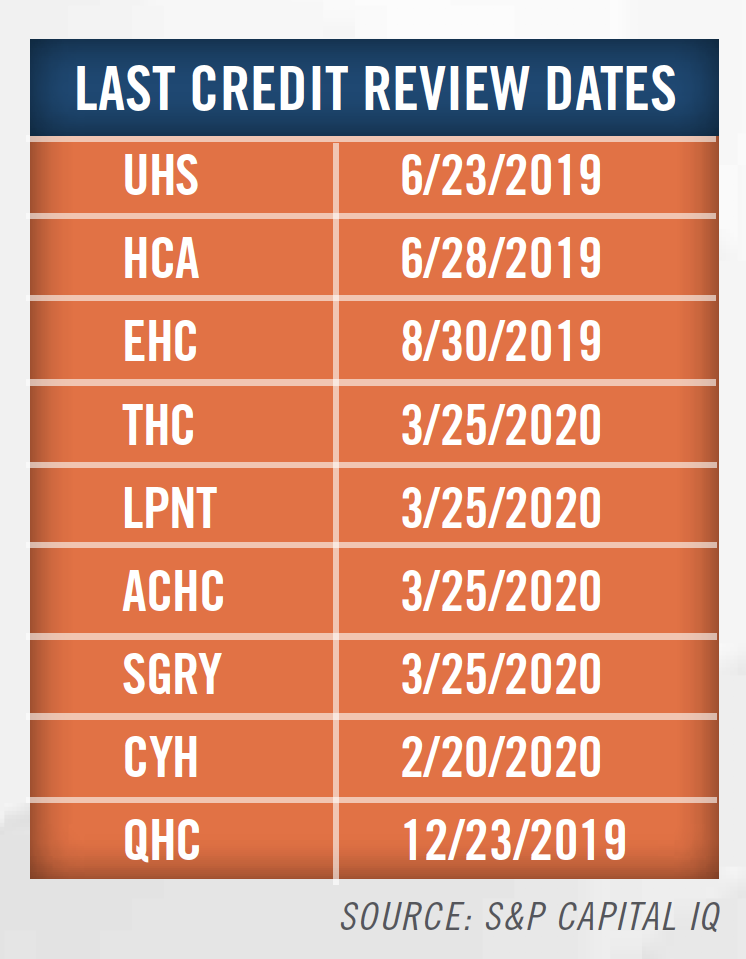

Publicly traded hospital operators have seen their share prices plummet as much as 70 percent for the 30- day period ended March 23, 2020.[8] Investors have implicitly indicated that, despite their size, publicly traded hospital operators are expected to experience similar financial headwinds as their non-profit and private hospital peers. As outlined in Figure 3, many hospital operators are highly leveraged, and a downturn in operating profit will put pressure on their ability to service debt, potentially further hampering their credit ratings. As shown in Figure 4, a decline in operating performance may lead to declines in credit ratings and outlooks, which may be viewed as an indication of financial distress.

Given the aforementioned challenges that hospitals across the nation will be facing, and their critical role in the COVID-19 pandemic, federal intervention has already begun. On March 18, 2020 President Trump enacted into law H.R. 6201: Families First Coronavirus Response Act. H.R. 6201 requires health issuers to fully cover COVID-19 testing and related visit costs, without imposing any costs (e.g., deductibles and copays) on the patients. Also stipulated in H.R. 6201 is a temporary 6.2 percent increase in the federal Medicaid funding rate to states. Both of these aspects of the law are likely to help hospitals provide patient care while partially mitigating the effects of receiving lower payments than otherwise accustomed to.

The CARES Act, which was signed into law on March 27, 2020, includes several provisions to assist hospitals, including:

1. A temporary 20 percent increase in the Medicare diagnosis-related group (DRG) weighting factor for inpatients with a primary or secondary diagnosis of COVID-19;

2. The Secretary of the Treasury may provide accelerated payments to hospitals on a periodic or lump sum basis and/or increase the amount of payment that would otherwise be made to hospitals under the program up to 100 percent (125 percent for CAHs);

3. Temporary suspension of Medicare Sequestration (i.e., a mandatory 2 percent reduction to Medicare fee-for-service claim payments) between May 1, 2020 and December 31, 2020; and

4. $180 million provided to Health Resources and Services Administration – Rural Health to expand telehealth services at rural critical access hospitals and rural tribal health and telehealth programs.

Still in deliberation is S.3559, the Immediate Relief for Rural Facilities and Providers Act of 2020. S.3559 contemplates several measures of financial relief for rural hospitals, as summarized below:[10]

1. Provide Immediate Relief for Rural Hospitals with an emergency mandatory one-time grant to CAHs and rural Prospective Payment System (PPS) hospitals equaling $1,000 per patient day for three months.

2. Provide Stabilization for Rural Hospitals with a one-time, emergency grant for CAH and rural PPS hospitals equaling the total reimbursement received for services for three months to stabilize the loss of revenue.

3. Encourage Hospital Coordination with a 20 percent increase in Medicare reimbursement for any patient in a rural hospital using the swing bed program to incentivize freeing up capacity in larger, overcrowded hospitals.

Within the state of Washington, one of the states hit hardest by COVID-19, at least 13 rural hospitals have less than 45 days of cash on hand with 5 of those hospitals facing imminent closure.[11] On February 11, 2020, The Chartis Center for Rural Health released findings that 453 rural facilities are considered to be ‘vulnerable’ to closure based on performance levels.[12] As the spread of COVID-19 continues, the financial strain on hospitals is expected to grow. It remains to be seen whether even with legislative actions, all hospitals will be able to absorb the financial impact of COVID-19, or whether it pushes certain hospitals into financial distress.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Based on our research, we believe hospitals in financial distress typically have a few viable options for recovery. In situations where the hospital is at risk of closure with little opportunity to improve operating efficiency immediately, HealthCare Appraisers has advised hospitals in facility and capital equipment sale-leaseback transactions. These transactions provide distressed hospitals the ability to use cash proceeds to fund deferred equipment investments, invest in deferred facility expenditures, fund shortfalls in operating cash flows, and re-focus on core operating service lines.

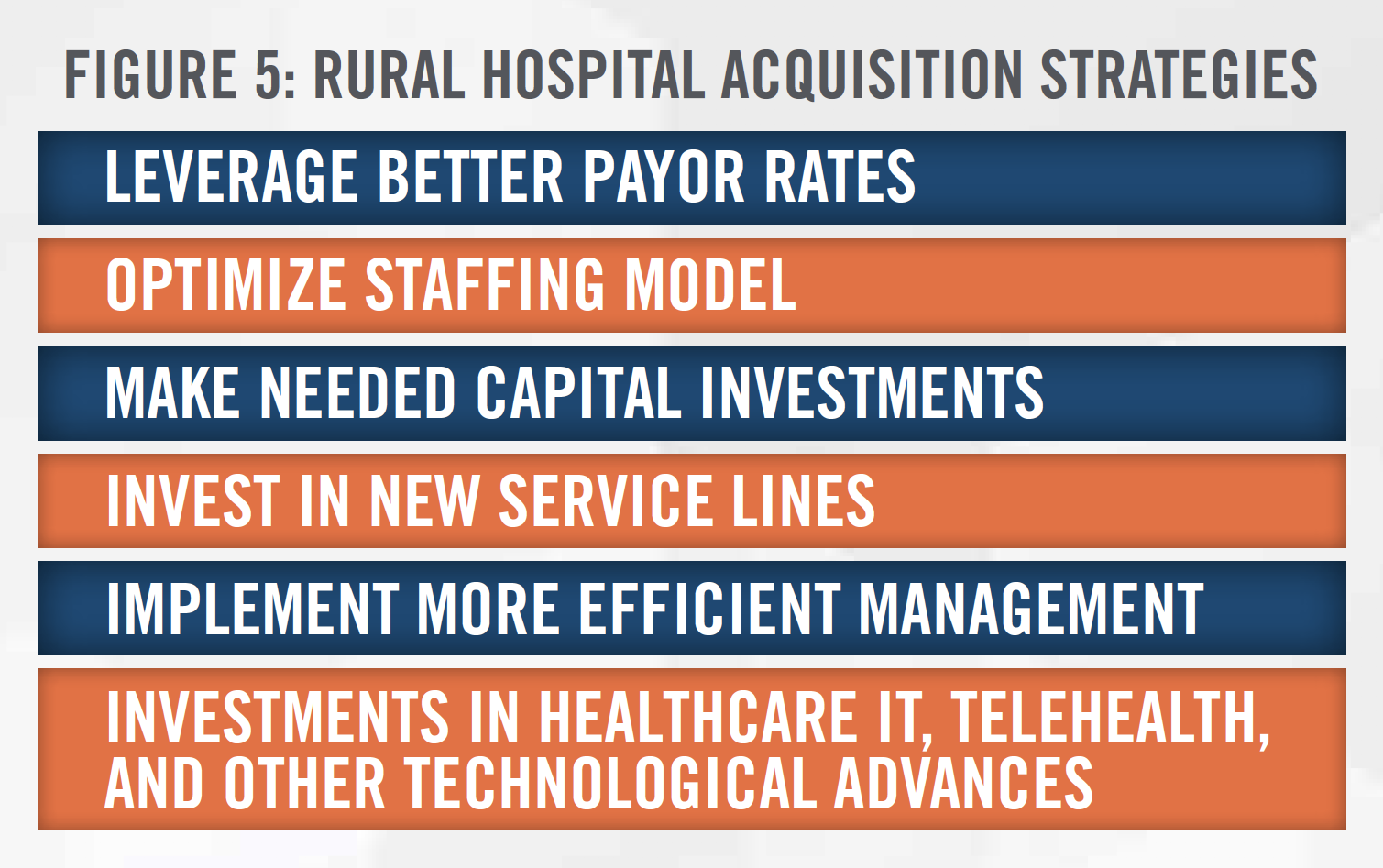

Alternatively, in situations that offer an opportunity for hospitals to continue operations by way of improved operating efficiency, we have assisted distressed hospitals with an acquisition by larger hospital systems. While many publicly traded hospital systems are closing the doors on their rural facilities for the promise of steady growth in more urban areas, there are also a handful of hospital systems that see opportunity in rural markets and are acquiring distressed hospitals with hopes of transforming them into thriving centerpieces of rural communities.

Figure 5 illustrates some of the tactics an acquirer may utilize to improve an acquired hospital’s operations.

In many distressed hospital transactions, a bargain purchase may occur. Bargain purchases result when the fair value of the acquired assets of a hospital is greater than the purchase consideration The difference between these amounts is recorded as a gain on the income statement of the acquirer. Please refer to HealthCare Appraisers’ publication on Current Trends in Hospital Transactions: 2019 for further detail on transaction structures and bargain purchases.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

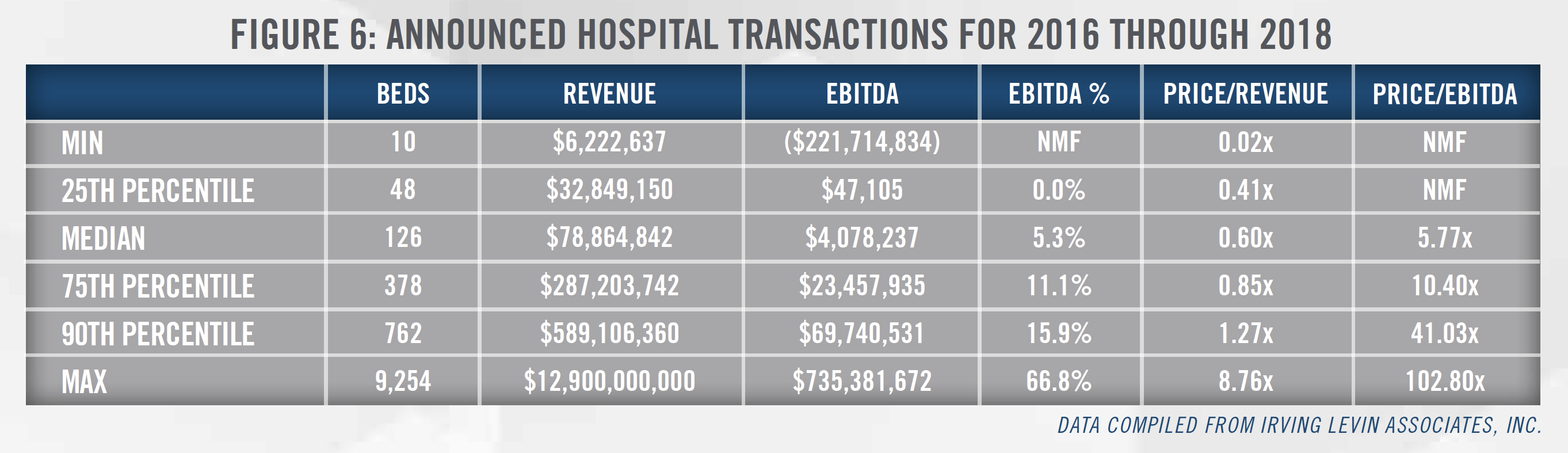

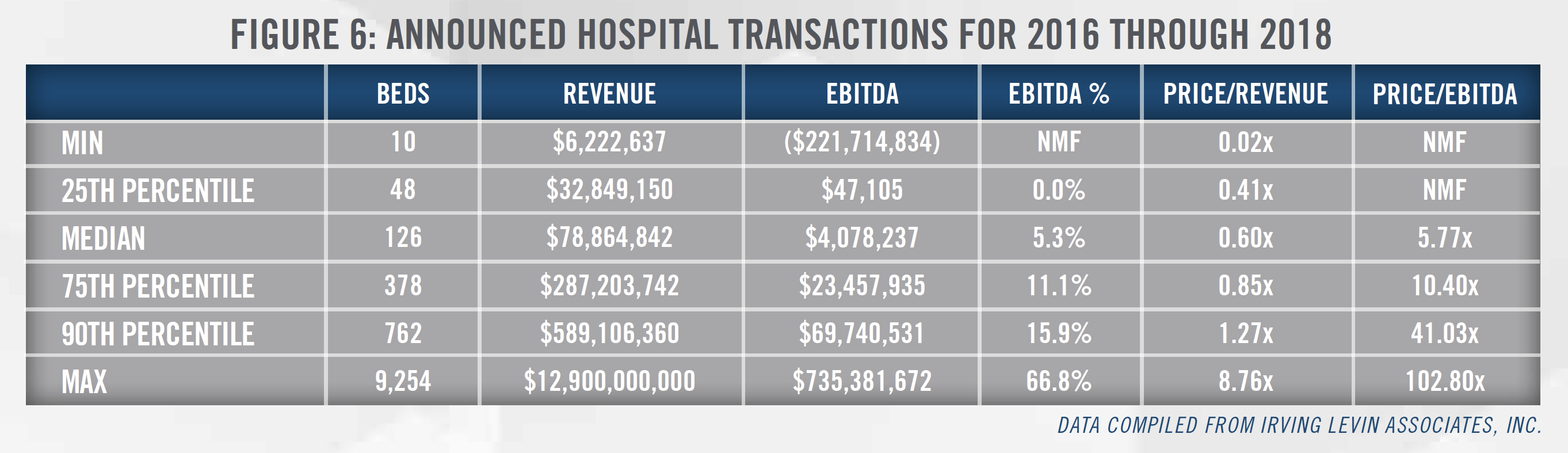

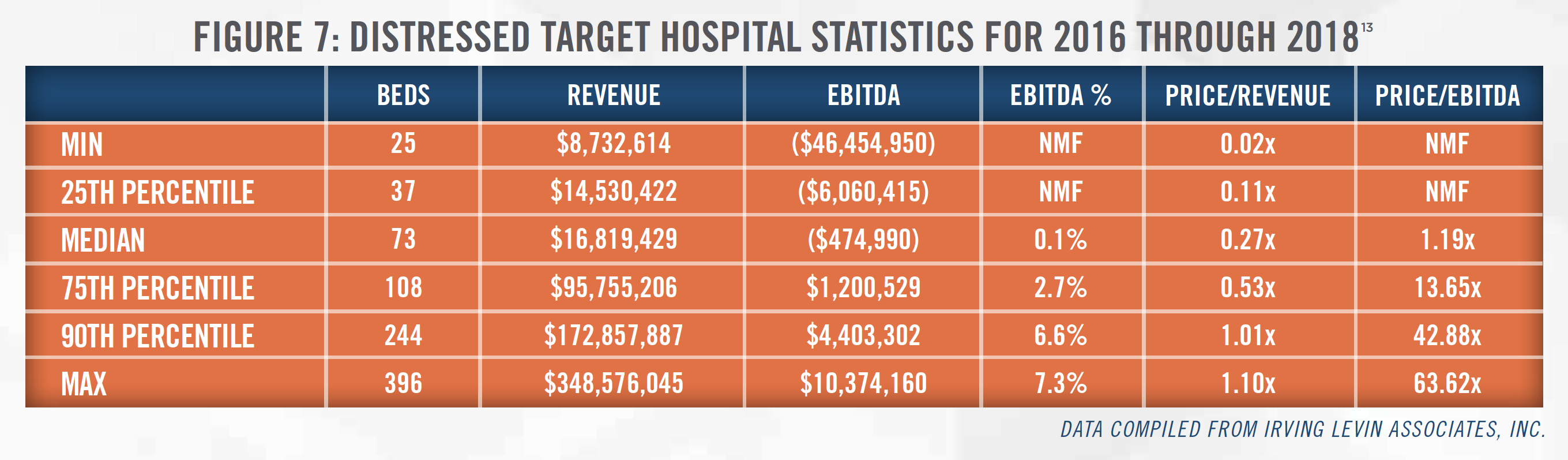

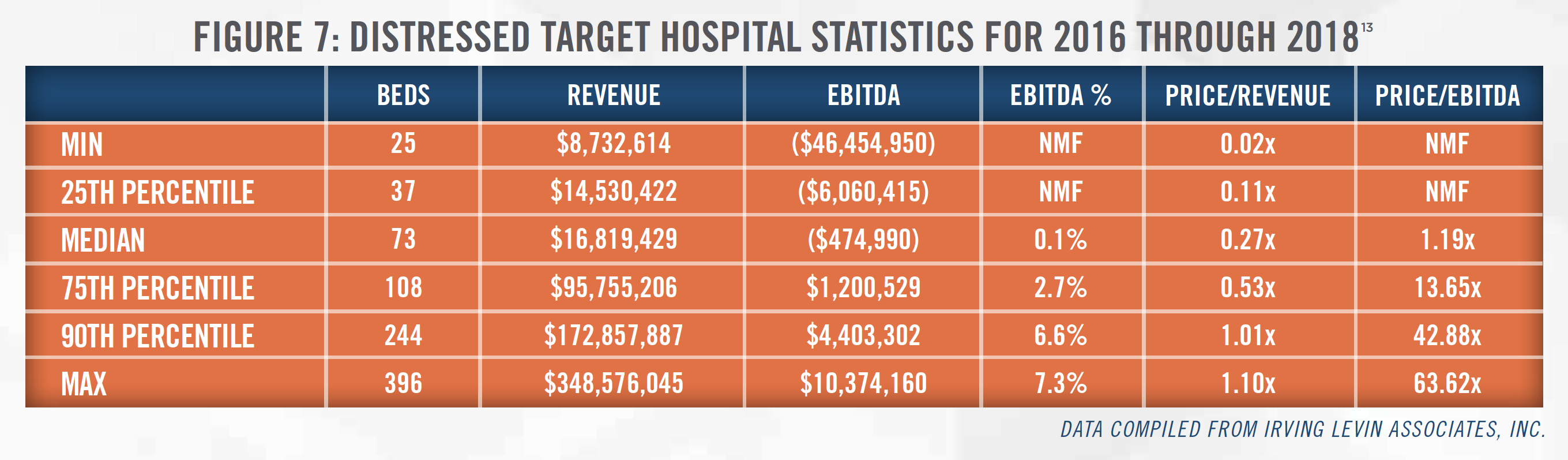

Valuing distressed hospitals warrants additional thoughtfulness and attention from an experienced valuator. Often, distressed hospitals have little to no earnings, which can create a roadblock for appraisers that do not possess expertise in distressed hospital transactions. HealthCare Appraisers has analyzed the priceto- revenue and price-to-EBITDA multiples paid for distressed hospitals. Figures 6 and 7 further outline these statistics for all 228 announced hospital acquisitions between 2016 and 2018 and the target hospital statistics specific to distressed hospital transactions from the same dataset.

We found that price-to-revenue and price-to-EBTIDA multiples for financially distressed hospitals can vary greatly depending on the assets and liabilities included within a transaction, as well as the age and condition of the subject assets. In comparing distressed target hospital statistics to those for all 228 target hospitals, we observed that price-to-revenue multiples for the distressed target hospitals ranged from less than 0.1x up to 1.1x, whereas price-to-revenue multiples for all target hospitals ranged upwards of 8.8x. Furthermore, the median price-to-EBITDA multiple for distressed transactions was 1.2x, which is only a fraction of the median multiple of 5.8x observed for all target hospitals. These findings suggest that the selection of lower multiples may be appropriate when valuing a distressed hospital. However, the appraiser must understand the specific attributes of the subject transaction in order to select appropriate market multiples.

When valuing financially distressed hospitals, it is also important to consider other elements that may add value to the facility, such as licenses, trade names, and certificates of need (“CONs”). In the case of a CON, a hypothetical buyer could potentially benefit from purchasing a hospital with a CON, as the presence of this asset eliminates time and costs involved in applying for a CON, as well as the risk of such application being denied. However, the value of such assets can heavily depend on various characteristics of the subject transaction. For example, a CON’s value depends on various factors, such as the transferability of the CON.

An appraiser might also consider the use of the adjusted net asset method in valuing a distressed hospital. In a hypothetical negotiation, a buyer and seller typically understand the time, effort, and money required to build a hospital and its reputation, and this method is generally believed to recognize the value associated with these efforts. The asset approach renders a value that does not consider the value of any future business generated by a hospital, but rather focuses on the cost savings a buyer of a hospital would likely realize relative to establishing a new hospital.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Over the past five years, HealthCare Appraisers has witnessed a rise in the number of transactions involving distressed hospitals. Our research indicates there are significant nuances involved in valuing distressed hospitals. To ensure a sound transaction, it is essential for the parties in such transactions to select an appraiser who understands these subtleties and will utilize the most appropriate valuation approaches to determine the value of a target hospital.

[1] HealthCare Appraisers utilized Irving Levin’s reported target descriptions to identify “distressed” hospitals. For purposes of this analysis, we classified any hospital with a target description noting “distress,” “financial instability” and/or “bankruptcy” as distressed. Additionally, for those transactions missing such key words but reporting negative earnings, HAI conducted market research to determine if the transaction involved a financially unstable hospital.

[2] Based on our review of Irving Levin Associates’ reported target descriptions and our proprietary hospital transactions database, these statistics are inclusive of 44 transactions for which the target descriptions note financial instability, financial distress and/or bankruptcy, as well as transactions that were followed by the subsequent closure or bankruptcy of the subject facility, which may be an indicator of financial distress.

[3] CMS Medical Learning Network Booklet, Critical Access Hospitals, July 2019.

[4] “Chapter 3: Annual Analysis of Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotments to States.” MACPAC. March 2019.

[5] Thomas, Sharita R., Pink, George H., Reiter, Kristin L. Characteristics of Communities Served by Critical Access Hospitals at High Risk of Financial Distress in 2019. Flex Monitoring Team. May 2019.

[6] Obtained from CMS press release posted to the CMS website dated March 18, 2020

[7] Mayo protects salaries until April 28, Post Bulletin, March 23, 2020, accessed March 25, 2020

[8] We note that many hospital operators saw their stock price rise notably on March 25, 2020 amid news Congress was nearing a deal on the emergency relief bill H.R. 748 (i.e., CARES Act) discussed below, which would provide billions of dollars in support for hospitals.

[9] Universal Health Services, Inc. (NYSE: UHS), HCA Healthcare, Inc. (NYSE: HCA), Encompass Health Corporation (NYSE: EHC), Tenet Healthcare Corporation (NYSE: THC), LifePoint Health (Private: LPNT), Acadia Healthcare Company, Inc. (Nasdaq: ACHC), Surgery Partners, Inc. (Nasdaq: SGRY), Community Health Systems, Inc. (NYSE: CYH), Quorum Health Corporation (NYSE: QHC)

[10] National Rural Health Association, accessed March 28, 2020 from: https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/blogs/ruralhealthvoices/march-2020/ruralamerica-needs-your-advocacy-now-(1)

[11] Based on a letter from the Washington State Hospital Association to Washington State Governor Jay Inslee dated March 20, 2020, last accessed on March 27, 2020 from: https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/6818594/Governor-WSHA-Emergency-Funding-Request.pdf

[12] Business Wire, “As Rural Hospital Closure Crisis Deepens, New Research from The Chartis Center for Rural Health Reveals Scope of Hospitals Vulnerable to Closure”, last accessed on March 27, 2020 from: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200211005662/en/Rural-Hospital- Closure-Crisis-Deepens-New-Research

[13] These statistics represent 13 transactions in which the target descriptions note financial instability, financial distress, and/or bankruptcy. Following two of these transactions, the acquired facility was closed or filed for bankruptcy protection.