![]() INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

At HealthCare Appraisers, we have analyzed numerous inpatient psychiatric facilities (“IPFs”) in a variety of contexts, whether for acquisition purposes, formation of joint ventures, financing, or market feasibility studies. Furthermore, we have also appraised management services, provider compensation, and ancillary services for fair market value considerations. IPFs are poised for continued interest among healthcare and financial participants; to that end, the authors present the current landscape of IPFs, as well as our outlook for 2023.

Over the past several decades, IPFs have faced numerous challenges and pressures. IPFs have suffered from shrinking government funding in this often-overlooked subsector of healthcare, as well as generally inferior reimbursement as compared to medical/surgical service lines. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the sector in both positive and negative ways. We are observing market participants, including non-profit/for-profit operators and financial buyers, investing within the sector with multiple avenues for growth.

![]() CURRENT IPF MARKET: SUPPLY AND DEMAND

CURRENT IPF MARKET: SUPPLY AND DEMAND

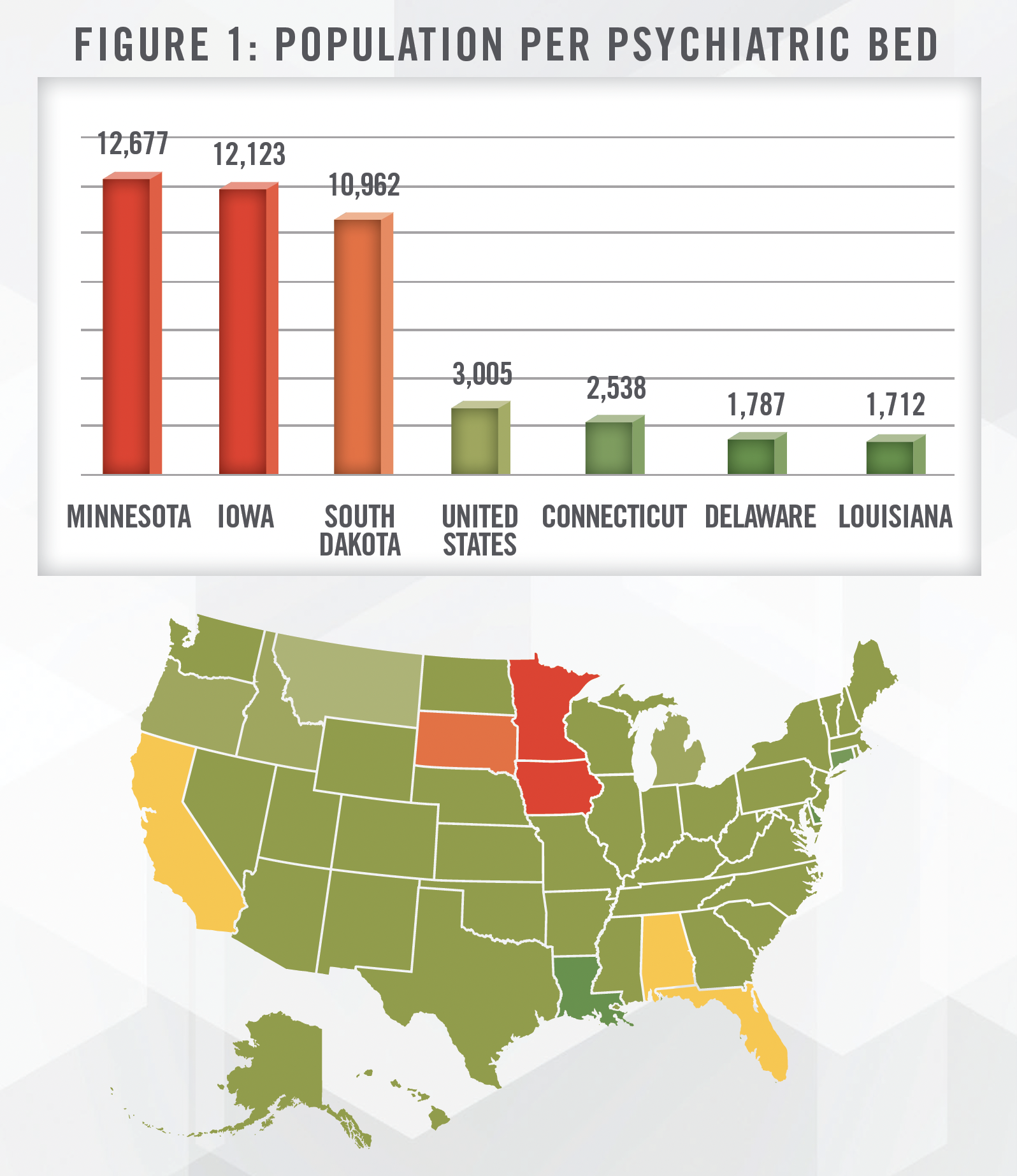

IPFs are a subsegment of the hospital market. IPFs are facilities (or specialized units within general acute care hospitals) that treat acute mental health conditions in an inpatient setting. They are distinct from inpatient substance use disorder (SUD) programs. As stated in an American Psychiatric Association (“APA”) paper, inpatient psychiatric beds have plummeted from nearly 560,000 in 1955 to a mere 101,000 in 2014.[1] The population of the United States has approximately doubled over this time period. SAMHSA’s 2020 National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS) estimates the number of inpatient psychiatric beds at approximately 112,000.[2] However, this supply shortage is not felt equally by all states, which maintain different levels of reimbursement from Medicaid and required regulatory compliance. Figure 1 outlines the ratio of state population as of July 2022[3] to state psychiatric beds for the three highest and lowest ratios. Although low availability states appear concentrated in the Midwest based on Figure 1, we also note that other similarly situated states are those with poor Medicaid reimbursement (e.g., California, Florida) or those with certificate of need requirements for IPFs (e.g., Alabama, Rhode Island).

Advances in medication-based treatment and reliance upon community centers have failed to keep pace with demand for acute psychiatric services. Instead, acute psychiatric patients have been housed within the correctional system, emergency departments in general acute care hospitals, nursing homes, or become homeless.

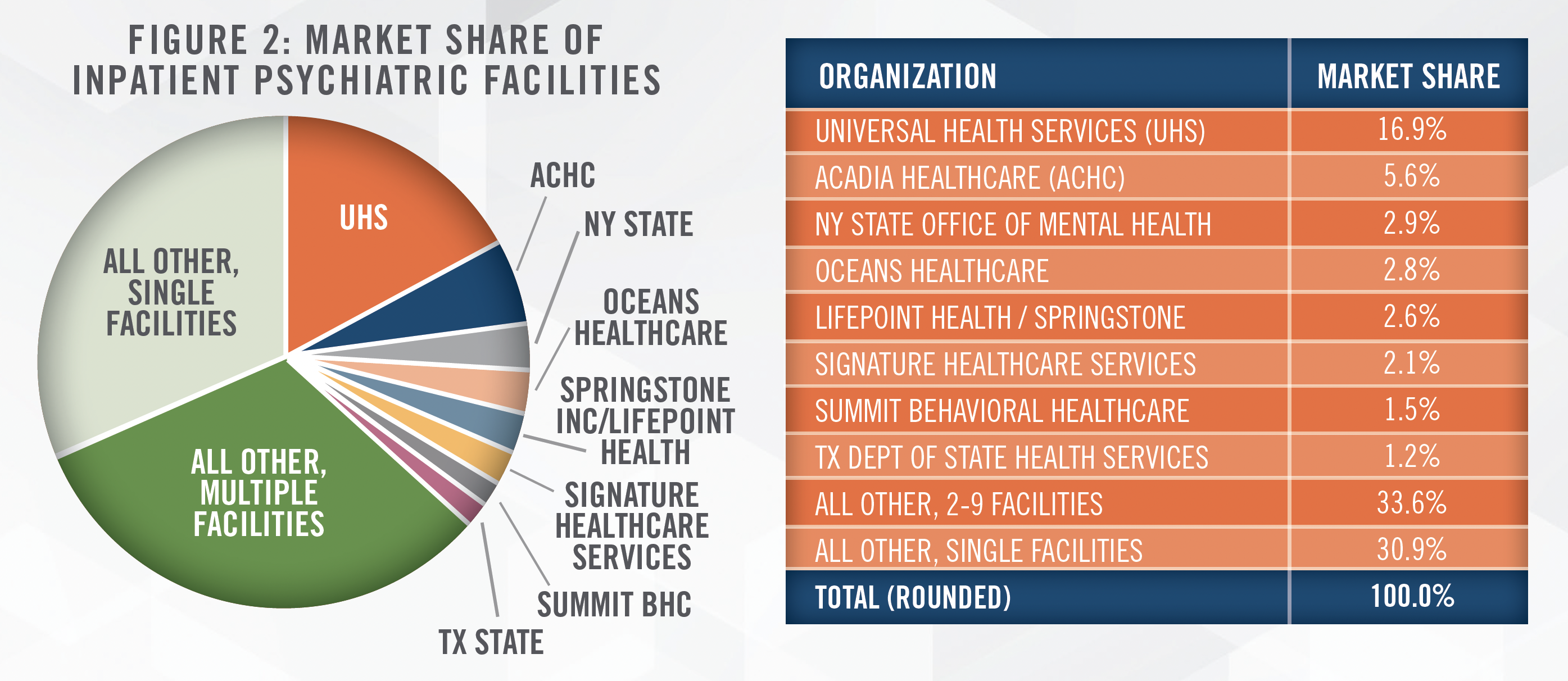

IPFs remain a fragmented market as shown in Figure 2, which outlines the number of IPFs owned by the top eight organizations. Universal Health Services and Acadia are publicly-traded operators with IPFs across the United States. Oceans Healthcare is backed by the private equity firm Webster Equity Partners (among others) and operates approximately 40 locations (of which, approximately half are IPFs) primarily in Texas and Louisiana, providing a range of services from inpatient beds to outpatient services like SUD treatment, adolescent care, and telehealth services. Lifepoint Health is another private equity-backed[4] operator of general acute and rehabilitation hospitals, for whom behavioral health marks a new, but growing segment. Signature Healthcare Services owns IPFs in California, Illinois, and Arizona under its “Aurora Behavioral Health” brand, and also offers SUD and other outpatient services. Summit Behavioral Healthcare is a private equity backed[5] national operator of 10 facilities most of which were acquired in the past five years. Summit Behavioral Healthcare filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in February 2023.

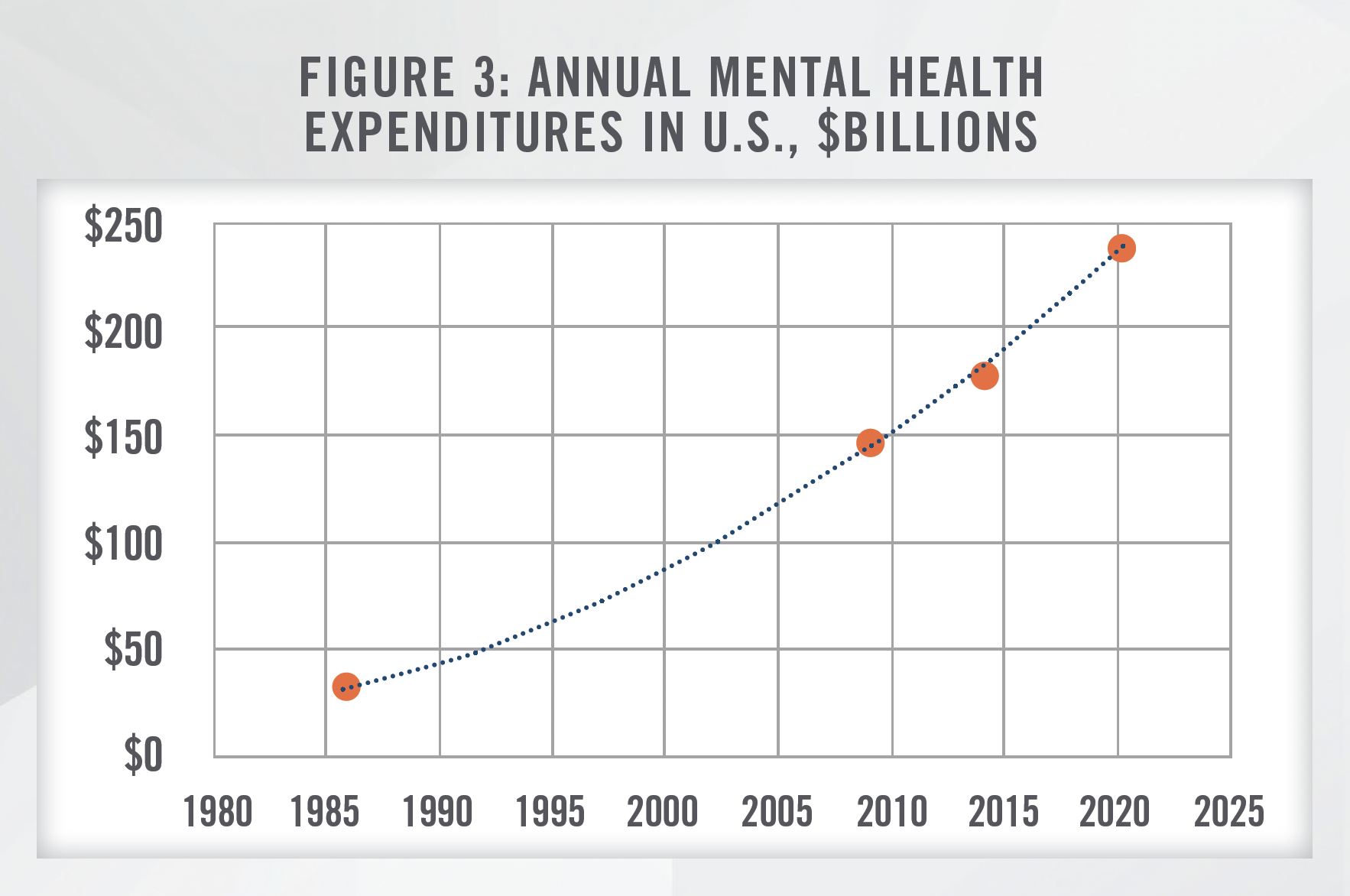

While IPF bed supply has declined significantly over time, demand for IPF beds has materially increased. Mental health spending has increased from $147 billion in 2009 to an estimated $238 billion in 2020, as shown in Figure 3—an annual growth rate of 4.5 percent.[6] However, demand is not limited to patients actually purchasing mental health services; a SAMHSA 2020 survey indicates that approximately 48 percent of adults afflicted with mental illness could not receive needed services.[7] While it is difficult to assess economic damages and losses associated with unmet need, we anticipate that government actions will seek to serve this need in the longterm. However, in the short-term, political pressures may prevent public funds from addressing this shortfall.

According to a June 2022 IBISWorld Report, psychiatric hospitals achieved an annual revenue growth rate of 2.6 percent from 2017 to 2022. From 2022 to 2027, annual revenue growth is expected to accelerate to 3.1 percent.[8]

![]() LEGISLATION AND REGULATORY CONCERNS

LEGISLATION AND REGULATORY CONCERNS

While the U.S. healthcare system is highly regulated, IPFs are burdened with an even higher amount of required compliance in considering both federal and state requirements.

Reimbursement Parity

A long-standing struggle in behavioral healthcare has been the goal of reimbursement parity, that behavioral healthcare services are reimbursed at levels equivalent to medical and surgical procedures. The Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 are legislative efforts which have historically failed to generate equivalent reimbursement. Although many advocates had hoped the COVID-19 pandemic could bring new recognition and compliance with these laws by payors, significant enforcement has yet to materialize, as evidenced by the January 2023 decision in Wit v. United Behavioral Health.[9]

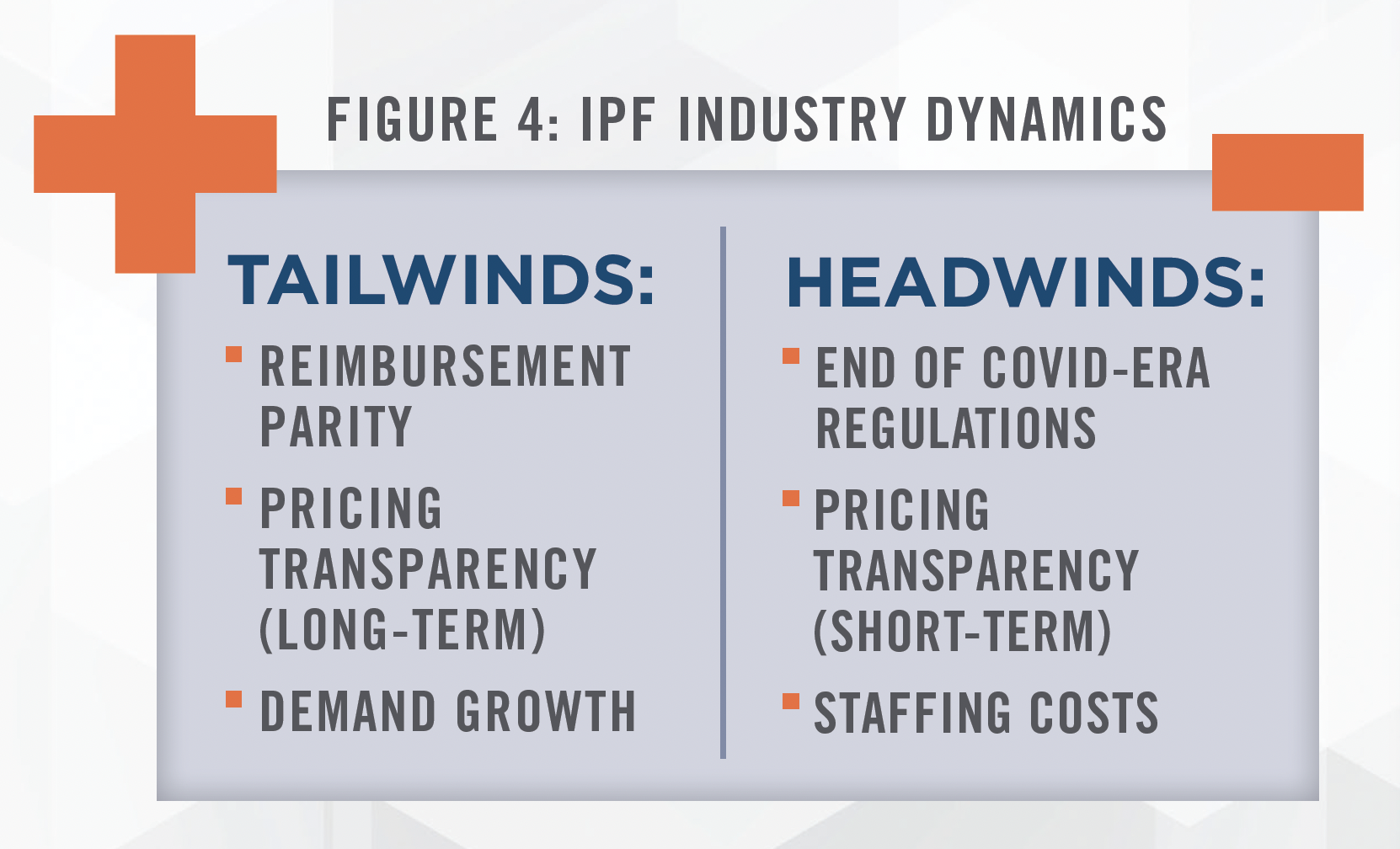

However, in October 2022, Congress passed the Mental Health Matters Act[10], which was subsequently signed into law by President Biden. The act gives increased enforcement powers to the Department of Labor with respect to behavioral healthcare parity laws. We will continue to watch how this latest law impacts payors, but continued focus in this area should serve as a tailwind for IPFs, at least in the long-term.

Emergency COVID-19 Regulations

The COVID-19 pandemic generated many emergency programs, relief funds, and suspension of existing regulations with the goal to preserve and expand patient access to medical care. IPFs benefited from favorable reimbursements for telehealth, as well as relaxation of methadone take-home protocols and other medication assisted treatment regulations, even if outpatient and SUD treatment centers benefited more directly. However, the public health emergency on which many of these changes are predicated is expected to expire on May 11, 2023. Many providers are advocating for the continuation of these policies given the benefits to patients. However, this uncertainty serves as a risk factor for IPFs.

Pricing Transparency

Historically, the reimbursement rates of public payors (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, etc.) have been available in the public domain. However, under the Public Health Service Act, hospitals are required to disclose negotiated rates with commercial payors beginning January 2021. The enforcement mechanisms for hospital disclosure have been weak, and some hospitals lack the necessary resources to comply with the requirements. However, the same Act also mandates that payors similarly disclose rates. By contrast, the penalties for non-compliance by payors are quite burdensome, and payors typically have more resources to comply with the requirement. This information from payors, in theory, should corroborate the reimbursement data from hospitals.

Based on our review of transparency files, we believe this data will be incredibly valuable to those who are able to access and act upon it. Before the Public Health Service Act, discussion of any particular commercial payor’s rates between providers could be construed as anti-competitive behavior, risking regulatory pitfalls. Arguably, such information is now in the public domain. Based on our experience to date, we believe payors are spending considerable resources in analyzing data from competitors and hospitals. However, hospitals are generally unlikely to reciprocate this research, based on a lack of resources. This is likely even truer for IPFs, which are typically smaller than general acute care hospitals. For now, we believe there is asymmetric information which will benefit payors in any renegotiations—at least in the short term.

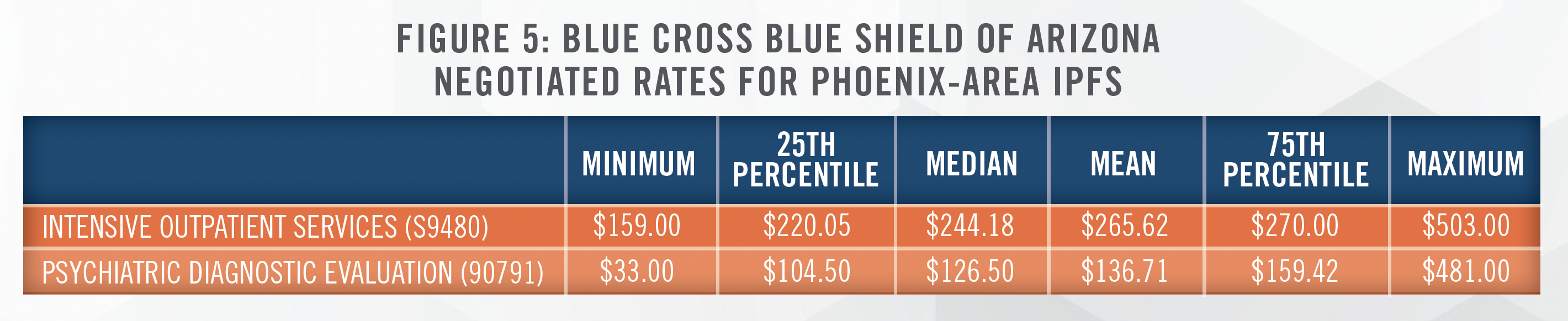

Our firm has used pricing transparency information to assist our hospital clients, either in the preparation of pro forma financial statements, in assessing market opportunities for the location of new facilities, assessing investment opportunities, and in the preparation of needs analyses required in connection with state certificate of need (CON) applications. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arizona’s February 2023 pricing file[11], summarized in Figure 5, shows the following range of reimbursement under its PPO plan for Phoenix-area IPFs.

IPFs ignoring the effects of pricing transparency will do so at their own peril; before pricing transparency, payors similarly suffered from a lack of knowledge of competing reimbursement rates. Currently, we believe payors are analyzing this publicly available data to their benefit, as they maintain the resources to analyze these technical files. In the long-term, however, we expect that pricing transparency will reduce the deviation of commercial payor rates. Additionally, symmetric knowledge of rates will reduce expenses associated with the contract negotiation process.

![]() DEVELOPMENTS SINCE COVID-19

DEVELOPMENTS SINCE COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has renewed interest in the broader behavioral healthcare sector as well as IPFs, as a result of the increased demand for such services. The pandemic brought on strategic opportunities, additional government funding and relaxation of regulations, offset primarily by staffing challenges and costs.

Joint Venture Opportunities

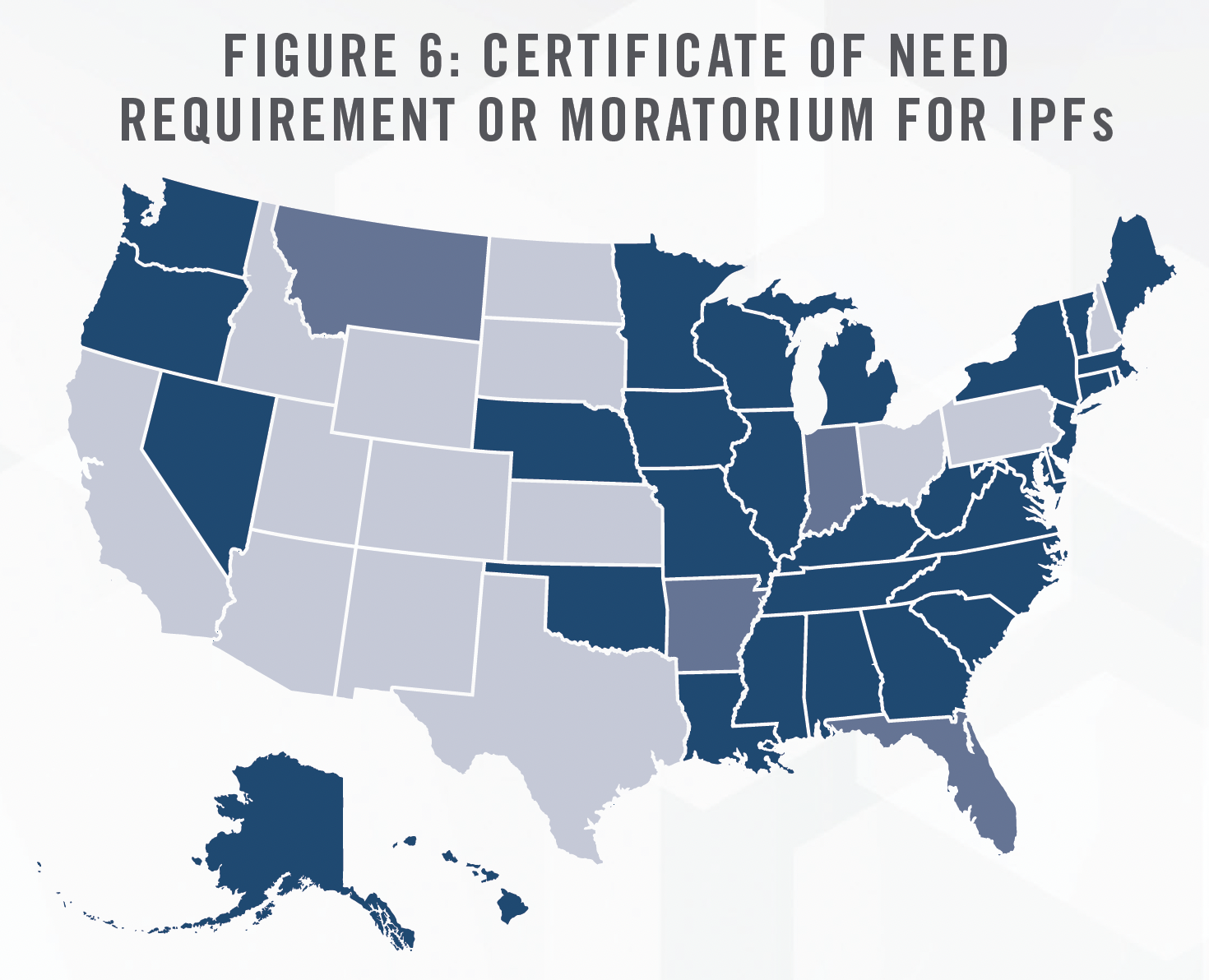

Many hospital operators are re-examining their existing IPF assets, finding them currently underutilized and/or unprofitable.[12] These operators are considering joint ventures by contributing IPF assets, such as real estate, hospital beds/units, clinical workforces, tradenames, and certificates of need. We have assisted multiple such clients in determining the value of these assets in contribution to joint ventures. In particular, certificates of need are valuable assets required in certain states, as outlined in Figure 6.

By joining forces with other experienced operators, IPFs may restore profitability to these capital-intensive assets. In its November 2022 earnings call, Acadia Healthcare Company, Inc. (NASDAQ: ACHC) described multiple such joint ventures with Henry Ford Health in Detroit, Michigan, and Covenant Health in Knoxville, Tennessee.

With our now 18 joint venture partners across the country and a solid pipeline of potential new partners, we expect this pathway to continue to be a strong driver of our growth.[13]

Chris Hunter

CEP, Acadia Healthcare Company

On February 7, 2023, private operator Lifepoint Health announced a majority ownership in Springstone, substantially increasing Lifepoint Health’s behavioral healthcare facility footprint.[14] Experienced partners not only bring profitability through higher, more effective utilization of the IPF, but also with more advantageous reimbursement contracts from commercial payors. Furthermore, with utilization at capacity at some IPFs, profit margins increase even more as IPFs shift beds to higher reimbursing commercial payors, effectively benefitting from price discrimination, as explained by Universal Health Services, Inc. (NYSE:UHS) CFO Steve Filton on its October 26, 2022 earnings call:

We’ve talked in previous calls about our relatively aggressive stance that we’ve been taking with a number of [commercial] payors in part because that’s a business in which we’ve been capacity constrained. So it makes sense to us or for us to go to our lowest paying payors and either require them to come up to market levels of reimbursement or terminate those contracts because we’re going to turn patients away. It makes sense to terminate those that are sort of the most inadequate, if you will, payors. [emphasis added]

Steve Filton

CFO, Universal Health Services, Inc. (NYSE:UHS)

UHS clearly leads the market for IPFs, as shown in Figure 3, so single-IPF operators may not have the same ability to dictate reimbursement contracts. However, ACHC also appears to be generating more revenue from its existing volume. As of its Q3 2022 filing, ACHC experienced same-facility revenue growth of 10.2 percent while patient days only grew 3.1 percent.[15]

Experienced operators not only provide expertise in core IPF services, but they also frequently develop other strategic ancillary services such as intensive outpatient programs (IOPs), outpatient medication services, telemedicine, psychotherapy services, SUD programs, or treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). IPFs are increasingly finding innovative ways to monetize beds beyond a traditional per diem payment system. We have observed HMO payors and forensic institutions[16] in need of frequent access to IPF beds, but who are unwilling or unable to develop such facilities on their own. Instead, contracts are structured so that the IPF receives a fixed payment for guaranteed access to a specified number of beds—regardless of whether those beds are utilized by patients or not. Similar arrangements have long been in use in skilled nursing facilities.

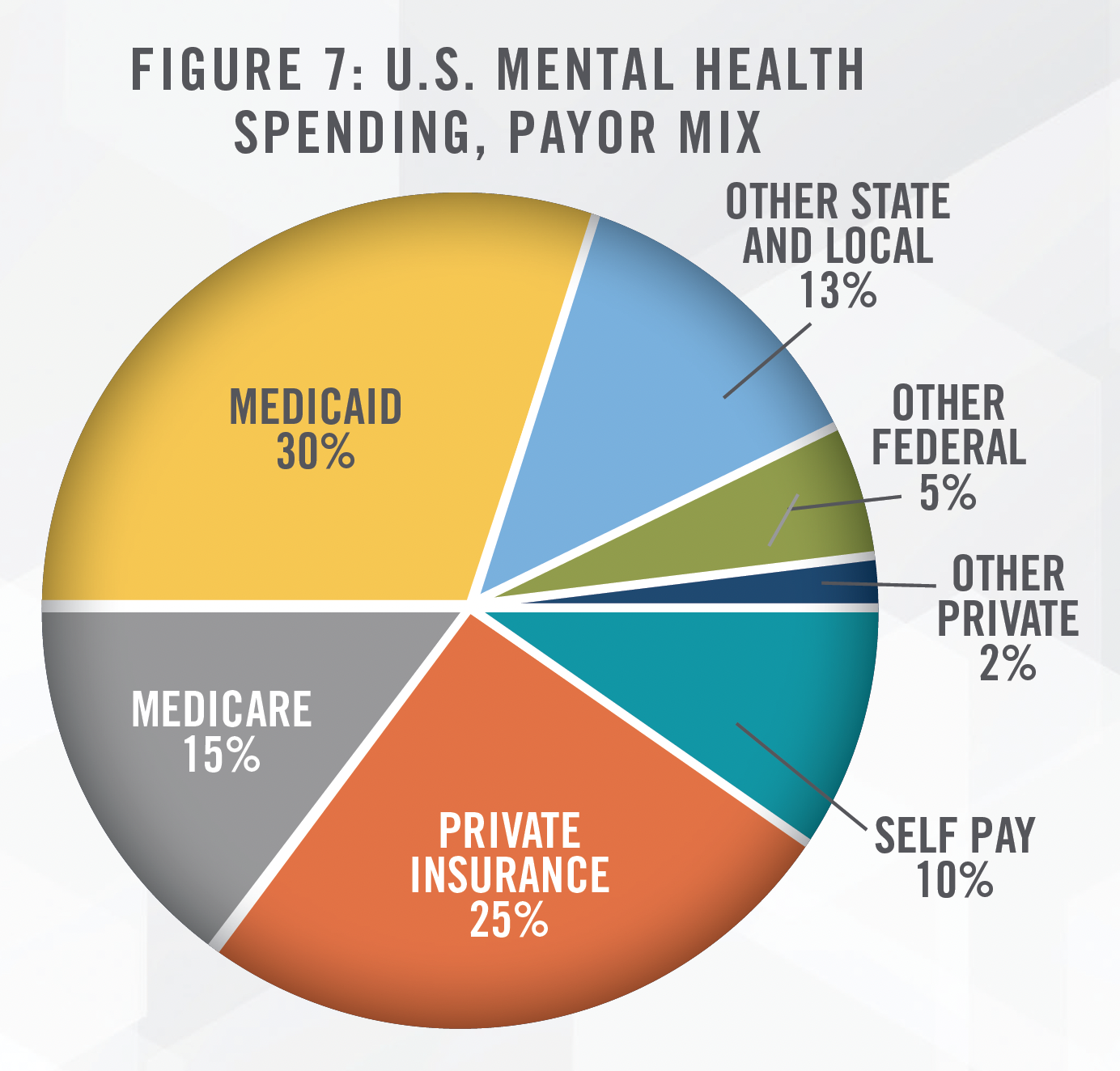

Medicaid Patients

Another possible strategy is the pursuit of Medicaid patients. Medicaid patients are not typically considered a well-reimbursing payor[17], but Medicaid beneficiaries do account for a significant percentage of total demand for IPF services. Medicaid is the source of payment for approximately 25 percent of patients seeking either mental health or SUD treatment[18], while SAMHSA 2020 estimates Medicaid at approximately 30 percent, as shown in Figure 7.[19] Based on our research and market studies, certain states such as California and Nevada reimburse significantly less than the costs of care incurred by IPFs. Others, such as Virginia and Wisconsin, reimburse at rates more comparable to Medicare. Both ACHC’s and UHS’s behavioral payor mix shows Medicaid (including Managed Medicaid) is responsible for over half of its revenue as of the nine months ending September 30, 2022.[20] Although commercial reimbursements are more desirable, Medicare reimbursement rates in certain states are sufficient to generate profit.

Medicaid enrollment is expected to suffer in 2023. As a public health measure at the onset of COVID-19, states were incentivized by the federal government to continuously enroll Medicaid beneficiaries automatically, without the usual annual re-application to assess eligibility; however, this requirement will end April 1, 2023, and federal incentives will end at the end of 2023. Over the course of three years, it is likely that some participants will no longer qualify for Medicaid enrollment, causing the pool of Medicaid enrollees to decrease. Even before the onset of COVID, Medicaid/CHIP enrollment had declined 2.6 percent to 72.4 million from December 2017 to July 2019.[21] As of September 2022, enrollment had grown 25.6 percent to 90.9 million.[22]

A possible offsetting factor from COVID may be the increase in mental health services offered to children and adolescent populations. COVID’s impact on children includes the loss of a parent, economic instability, or increases in abuse and online bullying.[23] Although the majority of efforts to meet children’s mental health needs are likely to occur in an outpatient setting or at schools, IPFs may be needed to serve the highest acuity cases.

Value-Based Care Arrangements and HMO

A frequent topic of discussion in the broader healthcare industry is the advent of value-based care (“VBC”) arrangements, which shift more of the risk on outcomes from payors to providers. Such VBC arrangements have developed more in the medical space than behavioral health, inroads are beginning to surface. For example, in 2022 the California Advanced Primary Care Initiative brought together five payors and an accountable care organization to provide both primary care and behavioral health. We believe VBC arrangements in behavioral health are more likely to manifest (initially, at least) as integrations within primary care. Although IPFs could be in a position to benefit from VBC arrangements, IPFs do not typically maintain the long-term relationships required to benefit from outcome-based rewards. Therefore, we expect the VBC trend in behavioral healthcare to initially grow in the outpatient setting. For now, we expect payors to prioritize access to IPFs, secured either by exclusive contracts or possibly acquisitions, especially if consolidation of IPFs gains steam. VBC arrangements with IPFs will remain a secondary goal.

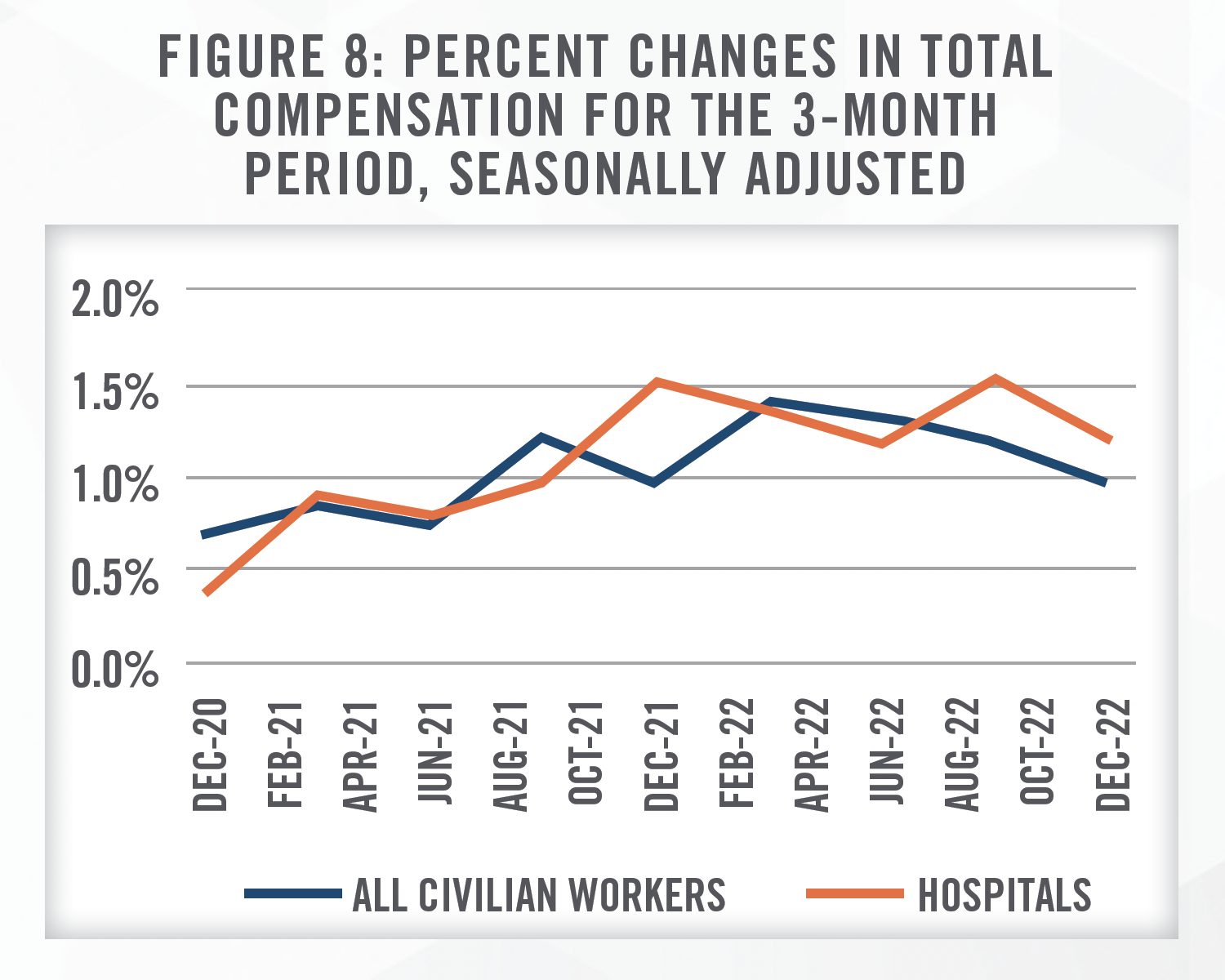

Staffing Pressures While many factors related to COVID-19 were positive for IPFs, staffing and payroll costs have continued to pressure profit margins. In the ACHC Q3 2022 earnings call, CEO Chris Hunter states that wage inflation had increased 5 to 7 percent for the recent year, higher than years pre-COVID. UHS CFO Steve Filton stated on the Q3 2022 earnings call the following about payroll inflation pre-pandemic:

In the acute [hospitals], it was 3 [percent], 3.25 [percent] pre-pandemic; it’s closer to 5 percent now. In behavioral health, it was 2 percent, 2.5 percent pre-pandemic. It’s closer to 4.25 [percent] now.[25]

Steve Filton

CFO, Universal Health Services, Inc. (NYSE:UHS)

IPFs (and hospitals more broadly) increasingly had to rely upon expensive contract labor (e.g., travel nurses) to either accommodate increased demand or to fill employment vacancies. At the time of the Q3 2022 call in November, Filton hesitated to provide guidance on future payroll costs, given their uncertainty. However, UHS had made progress in reducing the amount of contract labor required to fully staff beds, which corroborates our professional experience with hospital and IPF clients recently. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and shown in Figure 8, growth in the Employment Cost Index for hospital workers has declined since its peak in September 2022, although growth still remains above the broader civilian workforce.[26]

More recently, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Situation Summary for January 2023[27] showed unexpectedly high job growth in the U.S. Hospitals in January 2023 added 11,000 jobs alone, showing that facilities are succeeding in slowly filling vacancies, likely a necessary step before labor costs return to pre-pandemic growth levels. Since the onset of COVID, staffing difficulties have led many IPFs to shut down a portion of their units. Although staffing costs may be elevated, it may be more financially prudent to pay higher wages if units are able to be reopened as a result.

IPF Benchmarking, Transactions, and Valuations

IPF Benchmarking

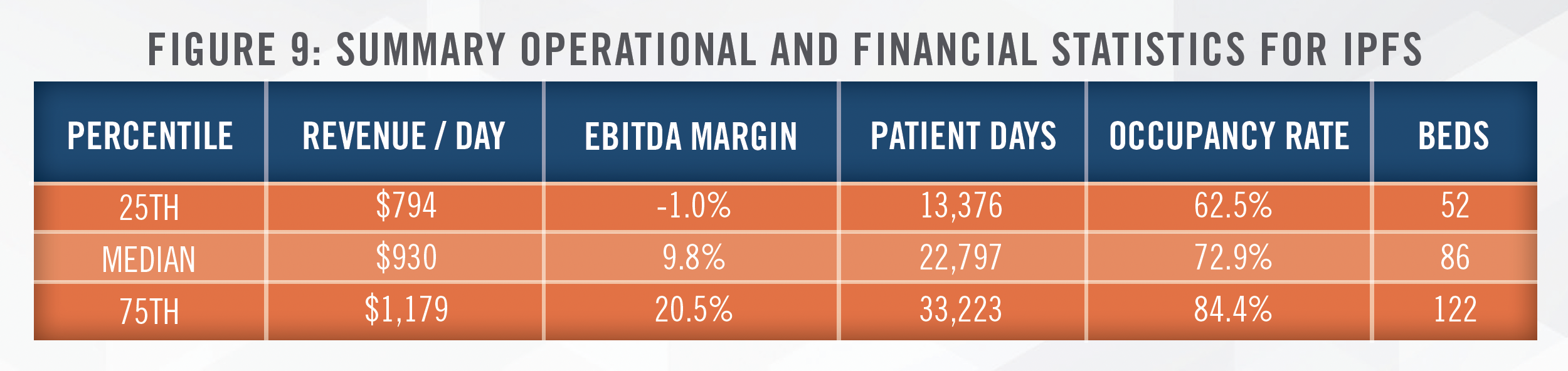

Based on our analysis of CMS Cost Report data for 362 IPFs[28], we observed the following summary statistics for 2021 in Figure 9. We also note that approximately 45 percent of these IPFs in 2021 operated on an unsustainable margin of below 7.5 percent.

IPF Transactions

The number of IPF deals likely peaked in 2021, before falling approximately 30 percent in 2022. 2021 corresponds to the final year of relatively loose financing conditions and low interest rates. Such financial conditions were of relative importance to financial buyers such as private equity firms, as well as operators dependent upon material levels of debt financing. Private equity buyers typically employ significant levels of debt in funding acquisitions; an increase in debt interest rates limits the ability of private equity to fund deals. However, S&P Global Market Intelligence reported a 21 percent year-over-year increase in dry powder for venture capital and private equity firms, which may offset some effects of increasing interest rates.[29] Operators who were already heavily reliant upon debt saw tighter credit conditions imposed by lenders, also constraining deals to some degree. In addition, capital gains tax considerations may have prompted some sellers to accelerate transactions.

Valuation Multiples

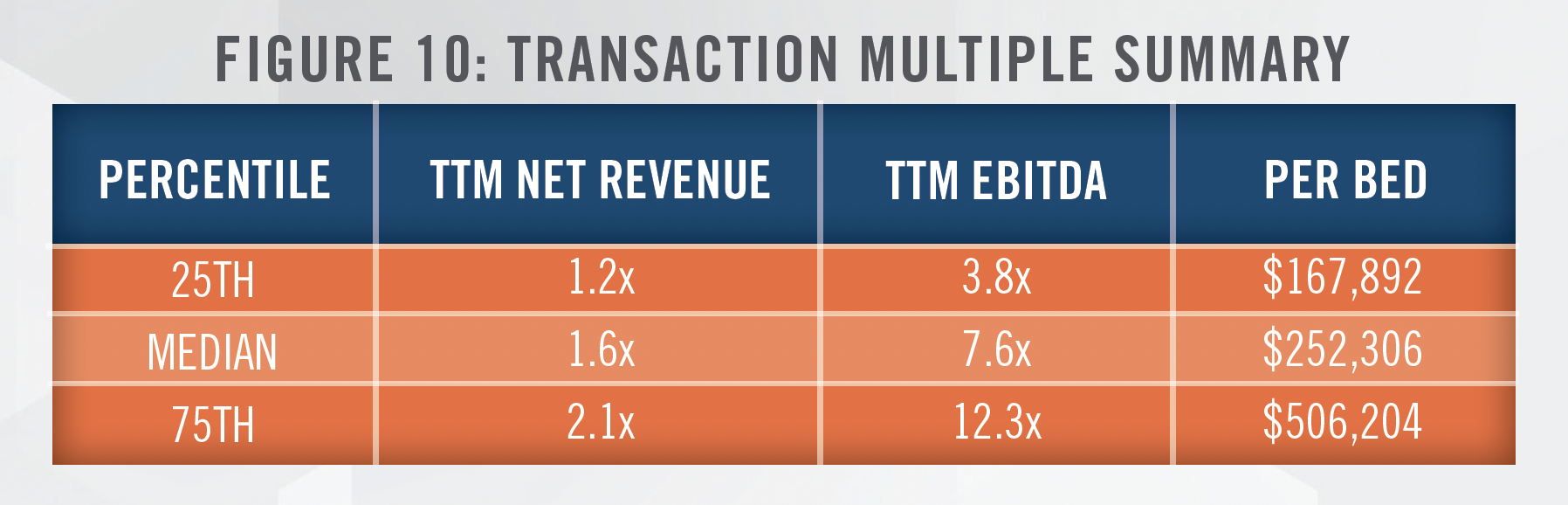

We have observed transaction multiples vary widely for IPFs, likely the result of unique deal terms or an understanding of the underlying assets acquired.[30] However, we have recently seen IPFs transact between 4.0x to 9.0x EBITDA, or 1.0x to 2.5x net revenue. On a per bed basis, multiples have generally ranged from $100,000 to $500,000 per bed. Based on transactions available to us[31] we have observed IPF transactions completed at multiples indicated in Figure 10.

Many factors affect the resulting multiple afforded an IPF, such as the scope of outpatient or ancillary services provided, the IPF’s payor mix, location, and ability to maintain adequate staffing levels to fully utilize available beds.

As previously mentioned, the Lifepoint Health/Springstone transaction closed on February 7, 2023 at a transaction price of $205,000,000.[32] This price represents an estimated 5.1x EBITDA multiple, 0.5x revenue multiple, and $150,000 per bed.[33] We note that while the majority of Springstone’s 18 IPFs maintained high levels of commercial reimbursement and provision of outpatient services, unit revenue and EBITDA margins were materially below average rates, leading to a multiple on the lower end the interquartile range shown in Figure 10.

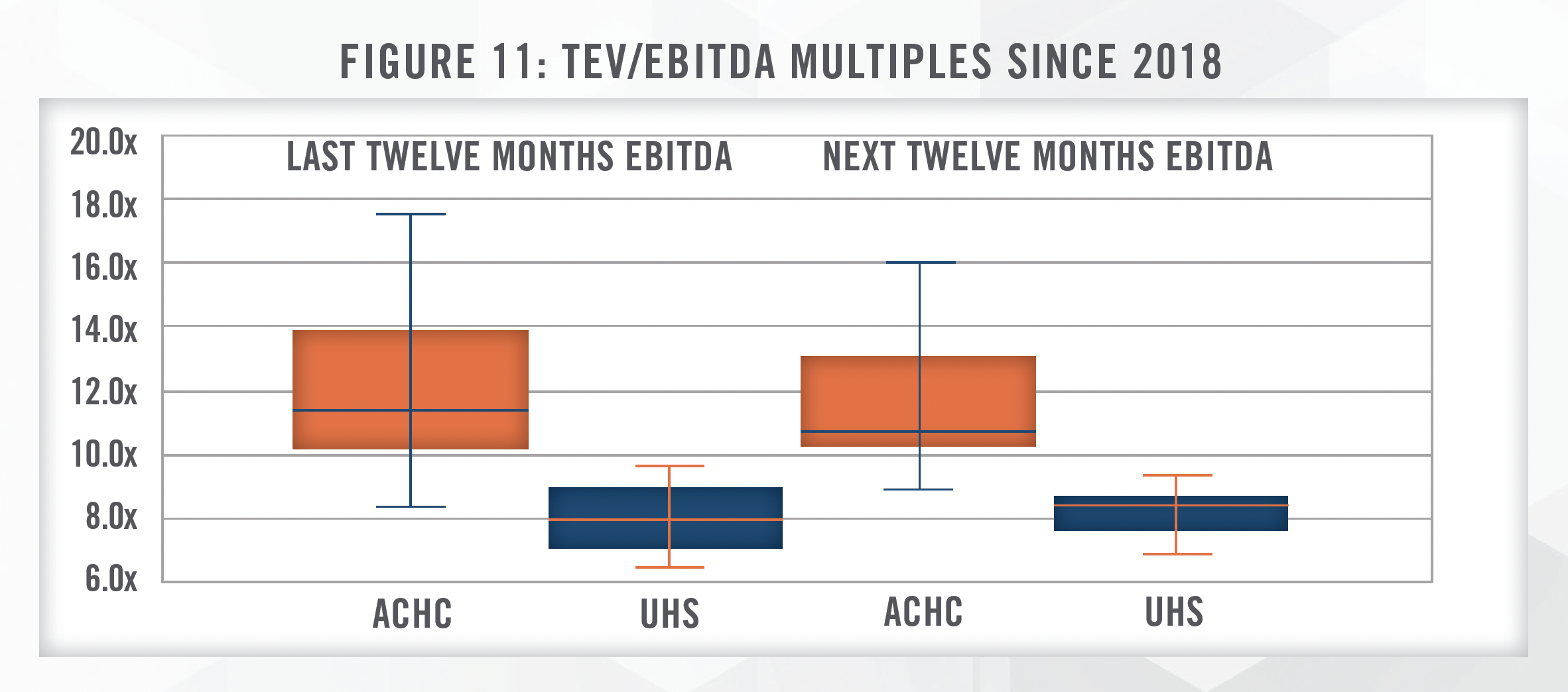

In the public markets, and as outlined in Figure 11[34], we can observe valuation multiples for both UHS and ACHC as another guide. ACHC is a pure-play on behavioral healthcare, while UHS is an operator of both general acute care hospitals and behavioral health facilities[35].

Both companies are currently trading at multiples above their median since 2018. UHS’s multiple reflects its heavy presence in the general acute care hospital subsector, which typically sees lower profit margins (currently 11.6 percent) compared to the behavioral health subsector (20.7 percent). ACHC is trading at approximately its 85th percentile since 2018, reflecting management’s stated intention of pursuing growth through multiple avenues, including joint ventures, de novo opportunities, and outright acquisitions.

One transaction trend we expect going forward is increasing activity and investment from payor groups. As patient demand for behavioral health services grows, some payors (e.g., Kaiser Permanente, CVS, United/Optum, etc.) may seek to bring entire operations under their purview, assuming it is financially feasible to do so. While de novo IPFs will be preferred36 in some cases, local restrictions (e.g., CONs, zoning restrictions) and capital requirements may change the calculus to favor either joint venture investments or outright acquisitions.

![]() CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

We expect to see increased interest and activity within the IPF market going forward. The COVID-19 pandemic loosened government regulations and increased funding, but ultimately risks a reversion to the status quo given the expected end of the public health emergency in May 2023. Staffing, and staffing costs, continue to be a challenge for IPF operators, but appear to be improving. If IPFs are not already doing so, they should consider additional services outside of core IPF offerings (e.g., outpatient therapies including psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and ECT/TMS) to leverage existing resources, providers, and patient referral patterns.

Existing local or regional operators will continue to leverage currently underperforming IPF assets into new joint ventures, while quality IPFs may contemplate outright sales. Large platforms will also seek these partnerships, building de novo facilities, and selectively acquiring facilities at moderated valuations as financial buyers are required to either consolidate recent acquisitions or be less aggressive given tightening of debt financing. We will be watching to see if major payors begin to jump into the industry more aggressively in order to rein in rising behavioral healthcare costs. Transaction valuations have declined from highs in 2021 into 2022, and we expect some continued moderation in 2023. High-quality IPFs will still be in demand, and entities with cash or favorable credit facilities are positioned to acquire IPFs at more reasonable valuations.

For more information, please contact:

Jordan A. Zoeller, MAcc, CFA, Manager at jzoeller@hcfmv.com or (303) 542-0109

Nicholas J. Janiga, ASA, Partner at njaniga@hcfmv.com or (303) 566-3173

[1] The 1955 count reflects only state-owned beds. To the extent there were privately owned beds in existence at the time, the staggering decline in beds since then is even more pronounced. American Psychiatric Association, “The Psychiatric Bed Crisis in the US: Understanding the Problem and Moving Toward Solutions”. May 2022. Last accessed February 9, 2023 from: https://www.psychiatry.org/getmedia/81f685f1-036e-4311-8dfce13ac425380f/ APA-Psychiatric-Bed-Crisis-Report-Full.pdf

[2] Last accessed February 15, 2023 from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35336/2020_NMHSS_final.pdf

[3] Based on data estimates from the United States Census Bureau.

[4] Lifepoint Health is owned by certain funds managed by affiliates of Apollo Global Management, LLC (NYSE: APO)

[5] The lead private equity firm is Patient Square Capital, LP.

[6] We note that in 2014, expenditures totaled $179 billion. Between 2014 and 2020, the annual growth rate was 4.9 percent, indicating an acceleration which doesn’t reflect the effects of COVID, as this SAMHSA report was prepared before COVID. Last accessed February 13, 2023 from: https:// store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4883.pdf

[7] Based on SAMHSA’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2019 and Quarters 1 and 4, 2020. Last accessed February 13, 2023 from: https:// www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35323/NSDUHDetailedTabs2020v25/NSDUHDetailedTabs2020v25/NSDUHDetTabs8-27,29,31pe2020.pdf

[8] IBISWorld, “Psychiatric Hospitals in the US”. June 2022.

[9] The facts and decisions of this case are beyond the scope of this article; Wit serves as a sign that the status quo on behavioral healthcare reimbursement parity has not significantly changed. National Law Review, January 30, 2023. Last accessed February 8, 2023 from: https://www. natlawreview.com/article/rules-enabling-act-key-to-new-ninth-circuit-decision-class-certification

[10] Congress.gov, House Bill 7780 – Mental Health Matter Act. Last accessed February 8, 2023 from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/ house-bill/7780

[11] Based on in-network rates for Plan Name 53901-PPO as of February 2023. Last accessed February 13, 2023 from: https://www.azblue.com/mrf

[12] Based on our review of IPF CMS Cost Report data for 2021, as summarized in Figure 8, we estimate that 25 percent of IPFs are unprofitable, while an additional 20 percent earn unsustainable EBITDA margins of less than 7.5 percent.

[13] Based on earnings call transcript provided by Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ database.

[14] “Lifepoint Health Acquires Majority Ownership Interest in Springstone”. Last accessed February 8, 2023 from: https://www.businesswire.com/ news/home/20230207006065/en/Lifepoint Health-Health-Acquires-Majority-Ownership-Interest-in-Springstone

[15] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, EDGAR database, Q3 2022 filing for ACHC. Last accessed February 7, 2023 from: https://www.sec. gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/1520697/000156459022036269/achc-10q_20220930.htm

[16] Typically representative of a jail or prison system.

[17] Medicaid also limits reimbursement for care for most adults under the age of 65 provided in “institutions for mental disease” if they operate over 16 beds, commonly known as the IMD exclusion. While CMS has expanded shorter-term stays for Medicaid MCOs, the exclusion continues to be a risk factor for IPFs. However, we believe the Medicaid population to be large enough to navigate this risk.

[18] MACPAC (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission). Last accessed February 13, 2023 from: https://www.macpac.gov/ medicaid-101/spending/#:~:text=Medicaid%20pays%20for%20about%20one,abuse%20treatment%20(SAMHSA%202019).

[19] This figure is based on data from SAMHSA Spending Estimates, and reproduced from “Projections of national Expenditures for Treatment of Mental and Substance Use Disorders, 2010-2020”. Last accessed February 13, 2023 from: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4883.pdf

[20] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, EDGAR database, Q3 2022 filing for ACHC and UHS. Last accessed February 7, 2023 from: https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/1520697/000156459022036269/achc-10q_20220930.htm and https://www.sec.gov/Archives/ edgar/data/352915/000156459022037046/uhs-10q_20220930.htm

[21] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Analysis of Recent Declines in Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment”, November 2019. Last accessed February 13, 2023 from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/analysis-of-recent-declines-in-medicaid-and-chip-enrollment/

[22] Kaiser Family Foundation, “10 Things to Know About the Unwinding of the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision”, January 2023. Last accessed February 13, 2023 from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-the-unwinding-of-the-medicaid-continuous-enrollment-provision/#:~:text=Medicaid%20enrollment%20has%20increased%20since.

[23] American Psychological Association, “Kids’ mental health is in crisis. Here’s what psychologists are doing to help.” January 2023. Last accessed February 8, 2023 from: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/01/trends-improving-youth-mental-health

[24] Healthcare Finance, July 27, 2022. “California Provider and five health plans adopt value-based primary care coalition.” Last accessed February 7, 2023 from: https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/california-provider-and-five-health-plans-adopt-value-based-primary-care-coalition

[25] As provided from earnings call transcripts provided by Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ database.

[26] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Cost Index – December 2022, released January 31, 2023. Table 1. Last accessed February 7, 2023 from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/eci.pdf [27] Colloquially, this report is referred to as “the jobs report”. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, released February 3, 2023. Last accessed February 7, 2023 from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm

[28] We removed IPFs which did not report sufficient data to calculate metrics, as well as removed outliers and other non-meaningful values.

[29] S&P Global Market Intelligence, “Global private equity dry powder approaches $2 trillion”. Last accessed February 16, 2023 from: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/global-private-equity-dry-powder-approaches-2-trillion-73570292

[30] Deal transactions reported from databases can be limited in detail that would fully inform the context of the multiple, such as any real estate acquired, earn-outs, clawbacks, or other terms of the deal that were of material value to the parties involved, but otherwise unreported.

[31] From Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ, Definitive HealthCare, LevinPro HC, and our work with clients

[32] As reported by Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ.

[33] Based on data aggregated by Definitive Healthcare for FY 2021, which sources data from CMS Cost Reports for each of the 18 Springstone IPFs.

[34] This multiple is calculated as Total Enterprise Value (“TEV”) to Next Twelve Months (NTM) EBITDA, as calculated monthly by Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ. Figure 11 presents the range of multiples since 2018 through early February 2023.

[35] UHS achieves approximately 43 percent of revenue and 57 percent of its EBITDA from its behavioral segment.

[36] Arguably, some markets may require de novo projects given the lack of available IPF beds in certain states. We have prepared diligence analyses for financing purposes for lenders in these cases.