Authors: Giulia F. Pace, MBA, CVA; Nicholas J. Janiga, ASA; and David Y. Lo, CFA

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the key role of healthcare organizations in helping their communities understand, process and respond to current events. While the current pandemic continues to place a heavy burden on providers, it has also presented an opportunity for these organizations to enhance their reputation and position their brands for the future.

![]() THE IMPORTANCE OF BUILDING A STRONG BRAND IN HEALTHCARE

THE IMPORTANCE OF BUILDING A STRONG BRAND IN HEALTHCARE

In the past decade, the healthcare industry has undergone fundamental structural changes. Increased consumer choice, consolidation, and the entrance of large, well-funded disruptors are three major trends changing the delivery of healthcare services. In this new, fiercely competitive marketplace, creating long-term, sustainable competitive advantages has become imperative to the success of healthcare organizations.

Outside the healthcare industry, branding is one of the most effective tools organizations have used to create sustainable competitive advantages and differentiate products and services from the competition. Traditionally, healthcare organizations have relied mostly on geographic proximity and the reputation of individual physicians to acquire patients. In today’s competitive environment, creating a cohesive organizational narrative is a task that healthcare organizations must embrace to remain relevant and create connections with the communities they serve.

Depending on the context, the concept of a “brand” can range from legally protectable visual and narrative elements that identify a company’s products and services, such as logos and trade names, to a wide range of intangible assets, such as marketing intangibles, customer goodwill, business processes and know-how. Trademarks and logos, the most common brand-related, legally protectable assets that may be owned by an organization, have very little worth unless they communicate values, qualities and/or character to audiences both inside and outside the organization.

Within healthcare, brand name recognition often translates to a loyal patient base, stronger negotiating power with insurers and suppliers, and the ability to recruit the most qualified physicians and team members. From a patient’s perspective, a known brand creates top-of-mind awareness and simplifies the decision-making process. On the payor side, insurers are incentivized to include healthcare organizations with strong brand name recognition in their networks because of the quality and value propositions communicated by the brand, or because plan members and/or their employers demand it. With an expected shortage of between 40,800 and 104,900 physicians by 2030[1], attracting and retaining high-quality clinicians is presumably a top priority for many healthcare organizations, the success of which will depend, in part, on brand recognition. Thus, a powerful brand is a differentiator healthcare organizations can rely on to build customer loyalty, grow market share, and, in turn, drive higher levels of profitability.

In the last few years, some major healthcare systems have led the way and invested significant resources in extensive rebranding efforts. These investments were either required by the system’s expansion into new markets, by the need to reflect the organization’s commitment to delivering excellent quality care or to appeal to a more sophisticated consumer. Consolidation, which has been a trend in the healthcare industry the past decade and is expected to continue for the foreseeable future, has been one of the primary drivers of these efforts. For healthcare systems merging to create mega health systems, an appropriate branding strategy is often needed to coalesce the entire organization around a common a set of values, and communicate those values to communities, executives, employees and other stakeholders.

Another trend putting an increased premium on branding is the “retailization” of the healthcare industry, a process driven by increasingly empowered patients. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, consumer-driven delivery models, such as telehealth, e-pharmacy, retail care, direct to consumer tests, and care at the point of the person, were projected to significantly outpace the growth for the rest of the industry. The reality of the past several months has provided additional fuel for the growth of these delivery models and exponentially accelerated the speed of consumer adoption. For traditional healthcare organizations, this means direct competition with well-funded disruptors that have strong brands and loyal customer bases, such as Amazon, Walmart, Walgreens and CVS, as well as competition with well-funded pure-play digital health companies, such as Teladoc, Amwell, Doctor On Demand and MDLive.

Traditional healthcare institutions are taking note, and as a response, many healthcare institutions have invested in comprehensive rebranding efforts in recent years. In 2019 alone, 22 hospitals announced or completed name changes or other rebranding efforts.[2] Some examples of these system-wide rebranding include:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Unlike traditional industries where a strong brand often translates into premium pricing for a company’s products or services, brand value in healthcare is largely created in a more indirect manner. As previously mentioned, a strong brand often results in an organization’s increased ability to attract and retain topquality physicians and clinical staff, market share growth driven by increased top-of-mind awareness from patients, and more favorable reimbursement due to the quality and value propositions communicated by the brand to commercial payors.

One way in which healthcare organizations are able to monetize their brand investment is through brand licensing, brand extensions or brand contributions to third parties. Licensing, the most common structure observed in the industry, involves the licensing of a defined set of rights to the brand by the brand owner to the licensee in exchange for a royalty payment. Royalty payments can be expressed as a percentage of revenue, as a fixed annual payment, or as a one-time, up-front, lump-sum payment. Another common structure observed in the healthcare industry is the contribution of a brand in exchange for equity in a joint venture.

When properly structured, licensing and contribution agreements can be extremely beneficial to licensors and licensees alike. For the brand owner, they provide a direct way to monetize the investment in the organization’s brand, gain additional exposure to the existing or new patient population, extend the brand into new markets, products or services, and enter into new strategic partnership without significant capital investments. For the licensee, the clear advantage is the ability to leverage the reputation of the licensor with limited financial exposure. While the potential benefits of these agreements can be significant, these arrangements bring inherent risks related to the ability to control and oversee the use of the brand, and the quality of services delivered by the parties.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

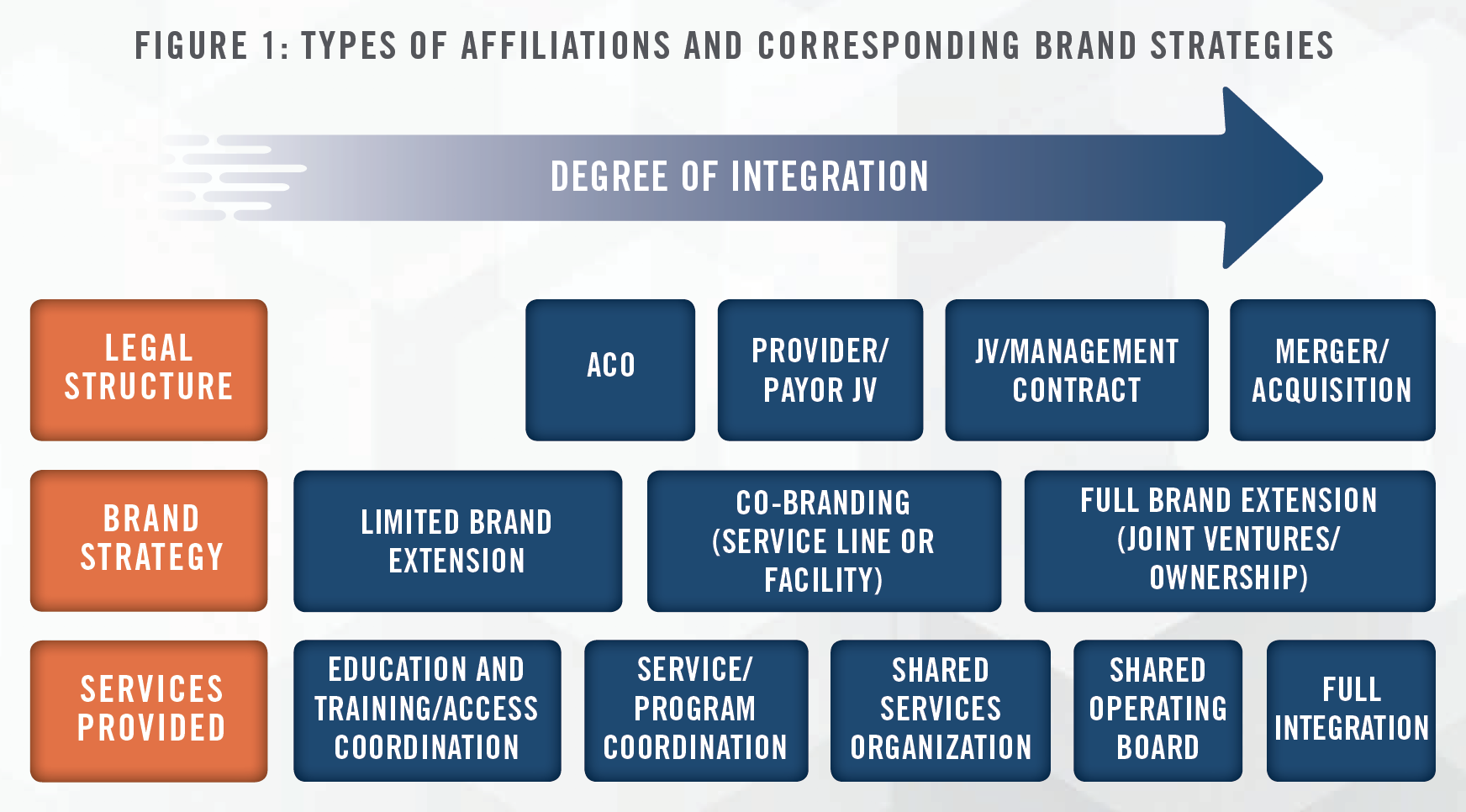

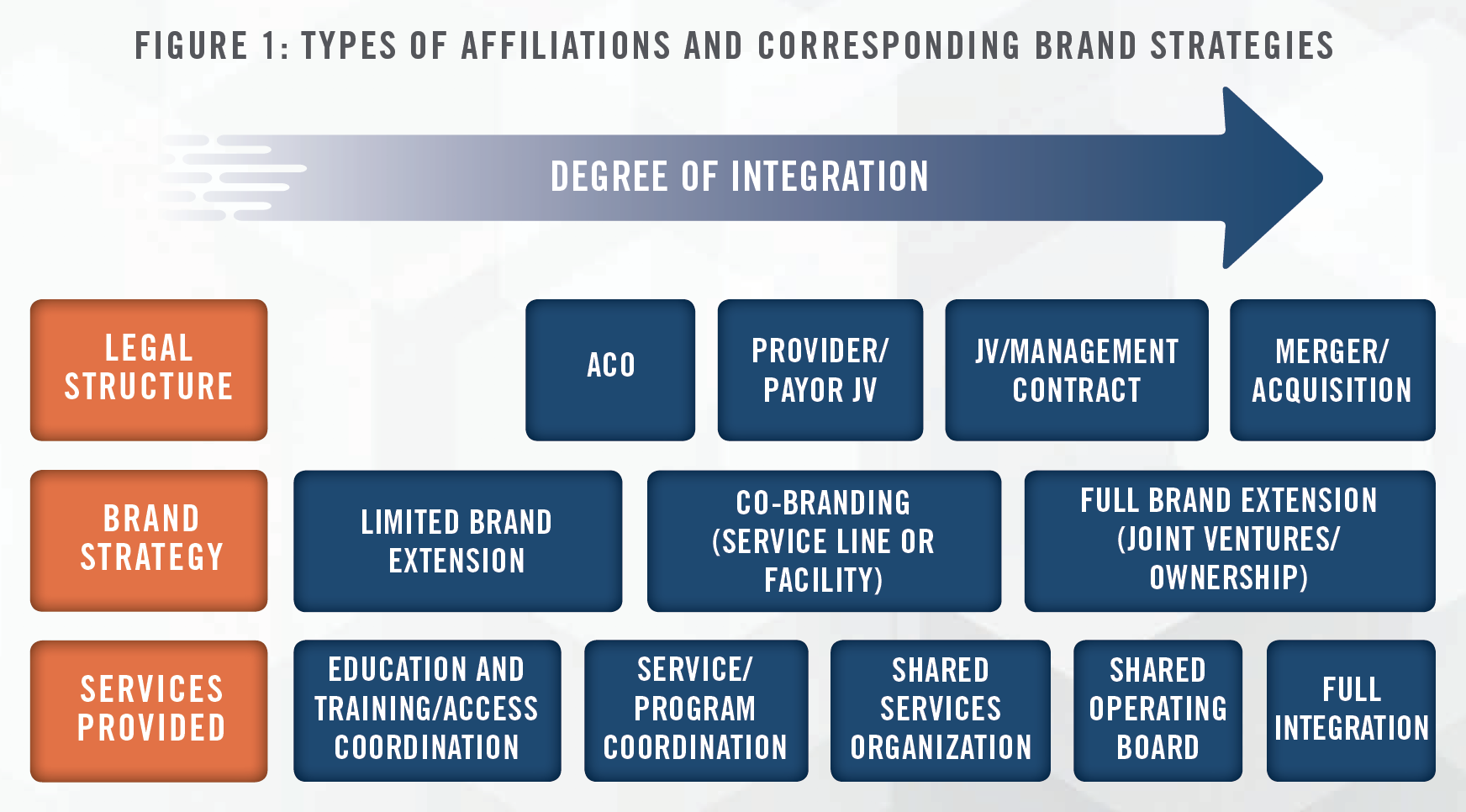

The last decade saw a number of high-profile brand licensing arrangements. A vast number of these involved academic health systems licensing the use of their brands to community hospitals, hospital systems serving rural areas, or specialty healthcare centers. Typically, licensing the use of the brand is a component of more comprehensive affiliation strategies that may take many forms, from agreements in principle to collaborate on quality and safety initiatives, to full brand contributions in exchange for an ownership stake in a joint venture entity

Affiliations between academic health systems and other healthcare providers allow academic health systems to leverage their investment in branding, research, and clinical and operational innovation to deliver high quality, cost efficient patient care at the local level. In the following sections, we outline various strategies that academic medical centers have pursued thus far.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Limited brand extensions are typically deployed in settings where collaborations between academic health systems and healthcare providers offer access to education opportunities, multi-disciplinary boards, peer-to-peer consultation and streamlined patient access. University of Utah Health Affiliate Network and the Mayo Clinic Care Network are examples of this strategy. From a branding perspective, this strategy allows local affiliates to enhance their brand by associating with high-profile, trusted healthcare brands, while extending the geographical reach of academic health systems, which are best suited to provide tertiary and quaternary care not available at certain local levels.

University of Utah Health developed an Affiliate Network to give hospitals and providers access to the clinical expertise, research, and resources in order to help serve patients within their own communities. The Affiliate Network includes 22 regional partners in Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and Nevada. Within these types of arrangements, there is typically no change of ownership and no change in a facility’s name. Instead, there may be limited co-branding to recognize the affiliation between the organizations.

The Mayo Clinic Care Network, launched in 2011, leverages Mayo Clinic’s reputation for high-quality care to provide network members with access to Mayo Clinic specialists and subspecialists, disease management protocols, care guidelines, treatment recommendations, reference materials and continuing education opportunities. Health systems, if accepted, will pay a fee to join the network, but will remain independent and gain access to clinical collaboration with the Mayo Clinic. Furthermore, members are able to enhance their own brand by associating through use of the Mayo Clinic Care Network logo. The Mayo Clinic Care Network includes members not only across the United States, but also internationally in countries such as Saudi Arabia, India, China and South Korea.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Co-Branding strategies typically reflect more extensive collaborations between healthcare organizations, such as program or service line coordination and clinical integration. Unlike limited brand extension strategies, full co-branding is typically granted after affiliates meet more strict requirements and assessments. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Network offers a prime example of this approach. MD Anderson Cancer Network locations, for instance, are co-branded facilities that have fully integrated cancer programs based on MD Anderson’s standards of care and treatment plans. Network participation occurs at different levels ranging from “Affiliates” to “Certified Member” to “Partner Members,” based on the level of integration. Affiliate relationships cover one specialty or modality-focused area, while Certified Member hospitals and health systems must meet national quality cancer care guidelines, which are reviewed on an ongoing basis. Finally, Partner Members are required to fully integrate their clinical cancer care operations with MD Anderson, and have a formal reporting relationship with medical directors at partner sites.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

LifePoint Health, which owns and operates community hospitals and other healthcare facilities in non-urban communities, is a prime example of a healthcare organization using joint ventures with academic health systems to enhance the profile of its hospitals. For LifePoint’s joint venture partners, this model provides a pathway to monetize their brand and to bring high quality, innovative healthcare services to communities outside their primary service areas.

In the joint venture between LifePoint Health and Duke University Health System, which covers 14 acute care hospitals and ancillary facilities, Duke University Health System receives a 3 percent equity interest in the newly formed joint venture entity, Duke LifePoint Healthcare, in exchange for its brand contribution.[3] While the JV provides an opportunity for Duke to strengthen its brand and generate additional revenue with minimal financial risk, there is a potential reputational risk for Duke.

LifePoint Health employed a similar strategy in its 2020 joint venture with Emory Healthcare. The genesis of the LifePoint Health – Emory Healthcare joint venture is an example of how brand affiliation strategies between healthcare systems tend to grow and evolve following increasing degrees of integration, and represents the latest step in an ongoing affiliate relationship between Emory Healthcare and St. Francis. In 2003, Emory and St. Francis began a cardiac services affiliation that aligned St. Francis’ electrophysiology program with Emory’s program. The heart/vascular relationship was then strengthened in 2016 following LifePoint’s acquisition of St. Francis, when Emory began to manage the hospital’s cardiothoracic surgery services. In 2017, St. Francis became a member of the Emory Healthcare Regional Affiliate Network[4], and in 2020, the relationship culminated in the formation of a new entity co-owned by Emory Healthcare and LifePoint Health and governed by a board with representation from both organizations.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

MidMichigan Health, a non-profit health system affiliated with the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) in 2013. As part of the affiliation agreement, UMHS contributed its expertise and brand in exchange for a minority interest in MidMichigan Health. UMHS’ ownership in MidMichigan Health began at less than 1 percent and may grow to as much as 20 percent over time.[5] As UMHS is nationally recognized for clinical excellence and physician expertise, this affiliation will benefit not only patients, who gain easier access to the advanced care and expertise available from UMHS, but will also enhance MidMichigan Health’s ability to recruit physicians. This is an example of a “hub and spoke” strategy where health systems establish a main campus or “hub,” which receives the heaviest resources and offers the most intensive medical services, which is complemented by satellite facilities or “spokes” that may offer more limited services.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Academic medical centers with strong regional brand recognition have expanded their regional presence through direct acquisitions. Examples of this include the expansion of the Medical University of South Carolina through the acquisition of four hospitals, UCHealth’s expansion throughout the state of Colorado through the acquisition of three hospitals, and Michigan Medicine’s expansion in West Michigan through the acquisition of Metro Health.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Given the growing importance of brand equity to an organization’s competitive positioning, and the various ways in which brand value can be unlocked through licensing arrangements, quantifying the value associated with brands is of key importance for all organizations. Similar to the valuation of tangible assets, intangible assets, such as trademarks (e.g., brands and trade names), can be valued using three generally accepted valuation approaches: the Cost, Market and Income Approaches.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The most commonly used methodology in the valuation of brands or trademarks, the Relief from Royalty Method, relies on a hybrid of the Market and Income Approaches. The Relief from Royalty Method is based on the premise that the owner of the intellectual property would have to pay a third party a royalty fee to license the intellectual property in the event that they did not own the rights to it. By owning the intellectual property, the subject entity is “relieved” of the royalty payments it would incur to license it from another party. This reduction in expense represents the economic benefit derived from the ownership of the intellectual property.

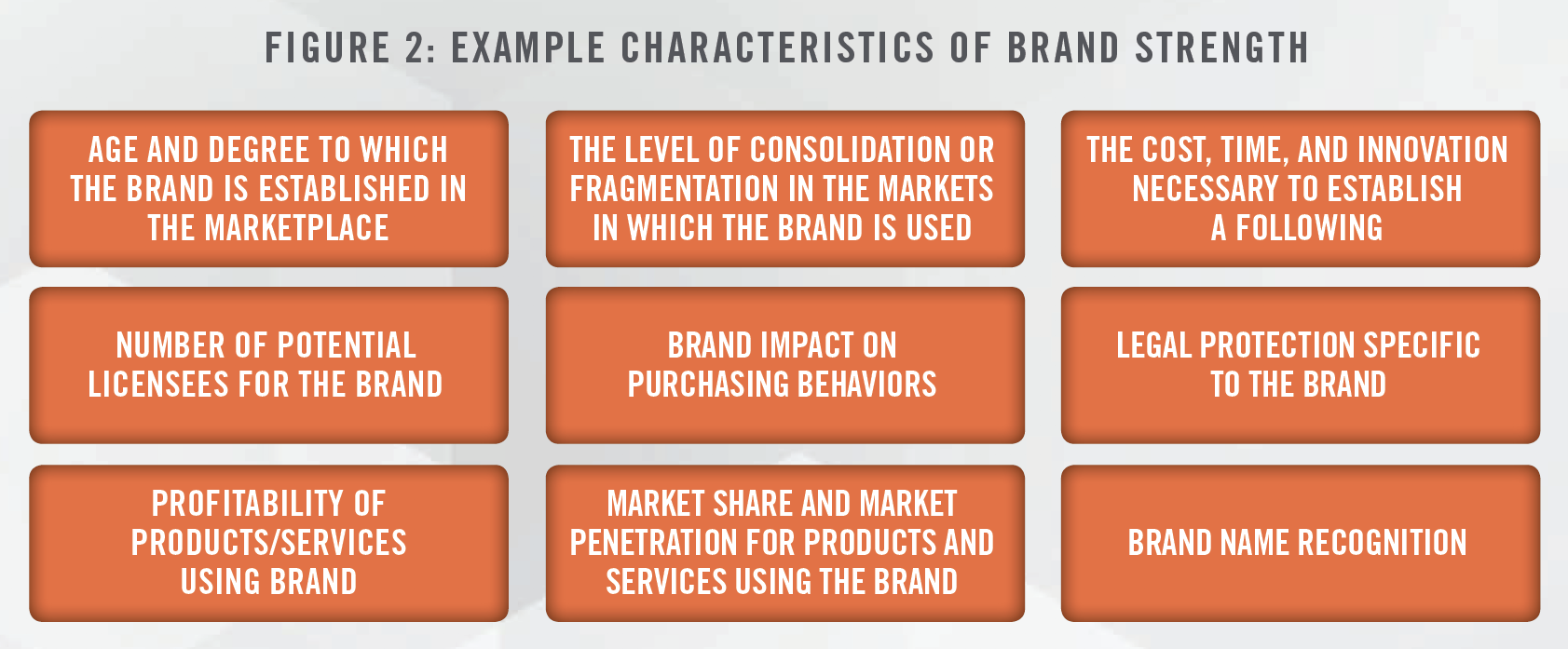

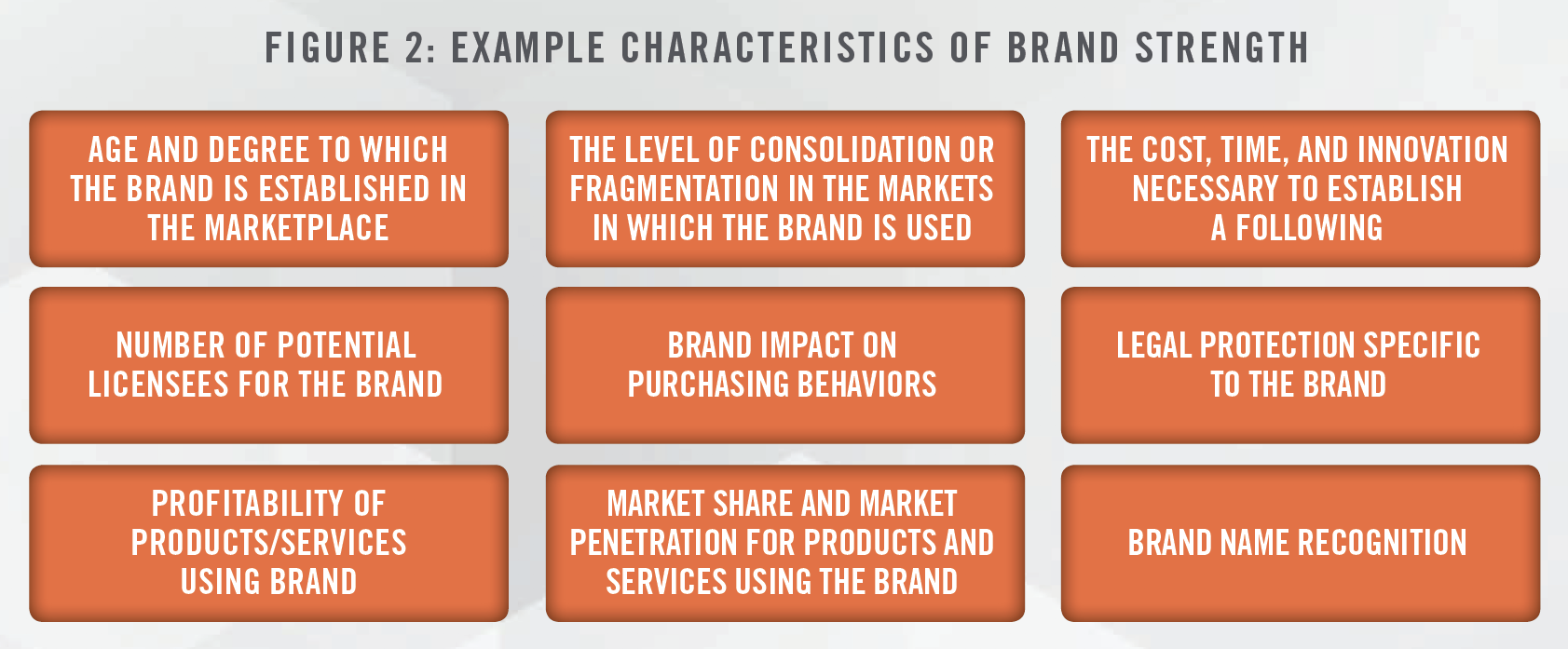

Under this methodology, the analysis begins with identifying arm’s-length licensing transactions for comparable intellectual property. Observed royalty rates for comparable transactions will identify the appropriate range of royalty rates applicable to the specific transaction. The applicable royalty rate is then adjusted to reflect the specific qualitative characteristics of the subject intellectual property, or brand strength, and the level of economic benefit to be derived from it.

One frequently cited framework related to the estimation of a reasonable royalty rate is from the court case Georgia-Pacific v. U.S. Plywood Corp[6]. In Georgia-Pacific, the court listed 15 factors (the “Georgia- Pacific Factors”) that can be used to support the determination of a reasonable royalty rate. While these factors were used to estimate economic damages related to patent infringement, the concepts can be applied to determining a royalty rate for trademarks. It is important to note that all 15 factors may not be relevant in all cases. The Federal Circuit stated that the Georgia Pacific Factors are not a “talisman” for royalty rate calculations.[7] We believe that the following characteristics outlined in Figure 2 tend to be relevant in determining the strength of a brand in the healthcare industry.

Once the applicable royalty rate is determined, the cost of the license, equal to the net present value of post-tax royalties saved over time, represents the value of the brand.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Robert Goldscheider was one of the pioneers of the “25 percent rule,” which since has been used by some to estimate appropriate royalty rates in intellectual property licensing negotiations. This rule suggests that a licensee should pay a royalty rate equivalent to 25 percent of its expected profit for the product that incorporates the IP at issue.[8]

Since then, there have been many studies examining the appropriateness of this rule. KPMG published a paper[9] which demonstrated a linear relationship between reported royalty rates and various profitability measures, but pointed out that royalty rates across industries do not perfectly conform to the implied royalty rates generated by the 25 percent rule. In addition, legal precedent stemming from the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Uniloc USA, Inc. vs. Microsoft Corp.[10] holds that this rule of thumb “is a fundamentally flawed tool” and that this rule could no longer be relied upon in determining a reasonable royalty rate.[11] Further, the court concluded that relying on the 25 percent rule as a starting point for applying the Georgia-Pacific Factors is also prohibited. “Beginning from a fundamentally flawed premise and adjusting it based on legitimate considerations specific to the facts of the case nevertheless results in a fundamentally flawed conclusion.”[12] While the use of “rules of thumb” may be used as a reasonableness check against other valuation approaches, we do not believe they should be used as a sole method in valuation.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

M&A activity, joint ventures, licensing agreements and tax reporting often necessitate formal brand valuation exercises. In a healthcare setting, the Anti-Kickback Statute, Stark self-referral laws, and Section 501(c)(3) of the US Internal Revenue Code dictate that the contribution of a brand in a healthcare transaction must be priced at fair market value to ensure the payments do not take into account the value of potential referrals of designated health services between the parties. However, as the strategic importance of branding in healthcare increases, so does the importance of measuring a brand’s contribution to an organization’s financial performance.

Relying on an independent third-party appraiser with deep industry expertise can provide a level of comfort when dealing with intangible assets where “value” can be perceived very differently by various parties. Additionally, an independent third-party appraiser can provide a consistent framework based on observed market data to help an organization understand how the brand is driving value, and articulate brand value in a language that is familiar to key decision makers responsible for steering financial resources within the organization.

[1] AAMC; “Research Shows Shortage of More than 100,000 Doctors by 2030,” last accessed on August 21, 2020 from: https://www.aamc.org/newsinsights/research-shows-shortage-more-100000-doctors-2030

[2] Becker’s Hospital Review; “Hospital rebrands: 22 name changes in 2019,” last accessed on August 21, 2020 from: https://www.beckershospitalreview. com/strategy/hospital-rebrands-21-name-changes-in-2019.html

[3] Modern Healthcare, “Extending Expertise” last accessed on August 19, 2020 from: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20130112/MAGAZINE/301129969/extending-expertise

[4] “St. Francis Hospital Joins Newly Formed Joint Venture Created by Emory healthcare and LifePoint Health”, last accessed on August 18, 2020 from: https://www.mystfrancis.com/hospital-news/st-francis-hospital-joins-newly-formed-joint-venture-created-by-emory-healthcare-and-lifepoint-health

[5] “Questions & Answers about the Affiliation between MidMichigan Health and University of Michigan Health System” last accessed on August 18, 2020, from: https://www.uofmhealth.org/questions-answers-about-affiliation-between-midmichigan-health-and-university

[6] Georgia-Pacific v. U.S. Plywood Corp., 318 F. Supp. 1116 (S.D.N.Y. 1970)

[7] Ericsson, Inc. et al. v. D-Link Systems, Inc., 773 F.3d 1201 (Fed. Cir. 2014)

[8] Intellectual Property: Licensing and Joint Venture Profit Strategies, Gordon V. Smith, Russell L. Parr

[9] KPMG; Profitability and royalty rates across industries: Some preliminary evidence; last accessed on August 27, 2020 from; https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/09/gvi-profitability.pdf

[10] Uniloc USA, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 632 F.3d 1292 (Fed. Cir. 2011)

[11] [632 F.3d 1315]

[12] [632 F.3d 1317]