Authors: David Y. Lo, CFA, ASA and Nicholas J. Janiga, ASA

![]() 1. OVERVIEW OF THE PHYSICIAN PRACTICE INDUSTRY

1. OVERVIEW OF THE PHYSICIAN PRACTICE INDUSTRY

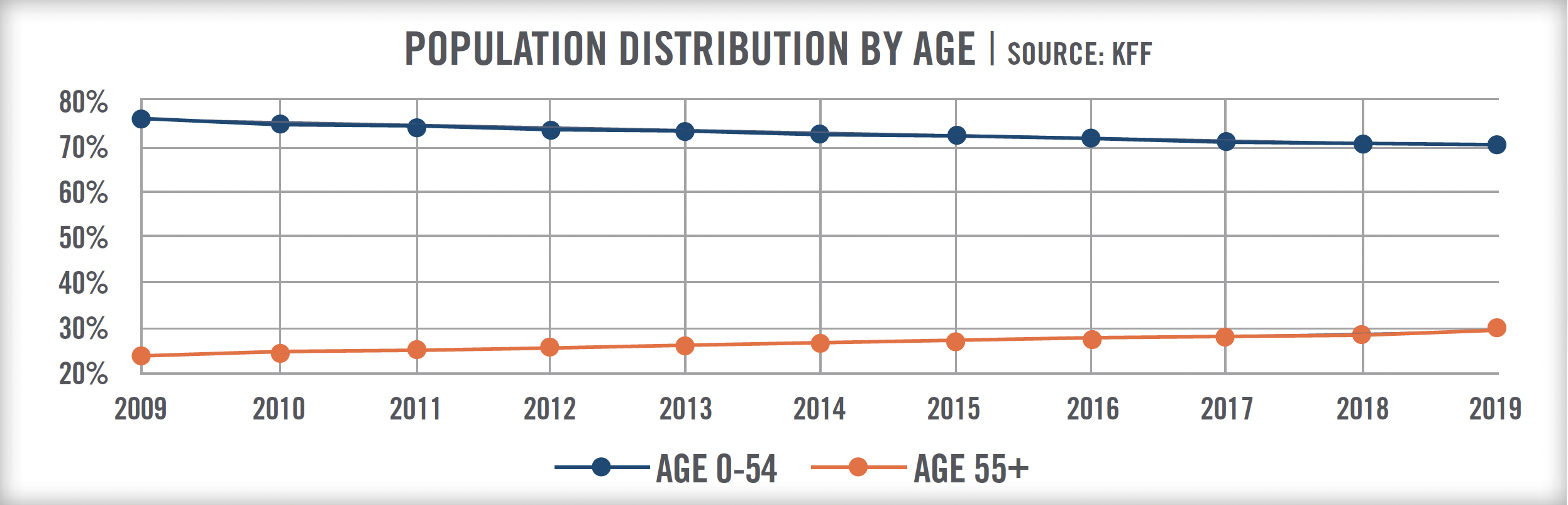

With slightly over one million active physicians in the United States, IHS Markit Ltd. projects a total physician shortage between 54,100 and 139,000 physicians by year 2033. Demand for physicians is expected to continue growing faster than supply, with the primary drivers for demand being population growth and the aging of the population.

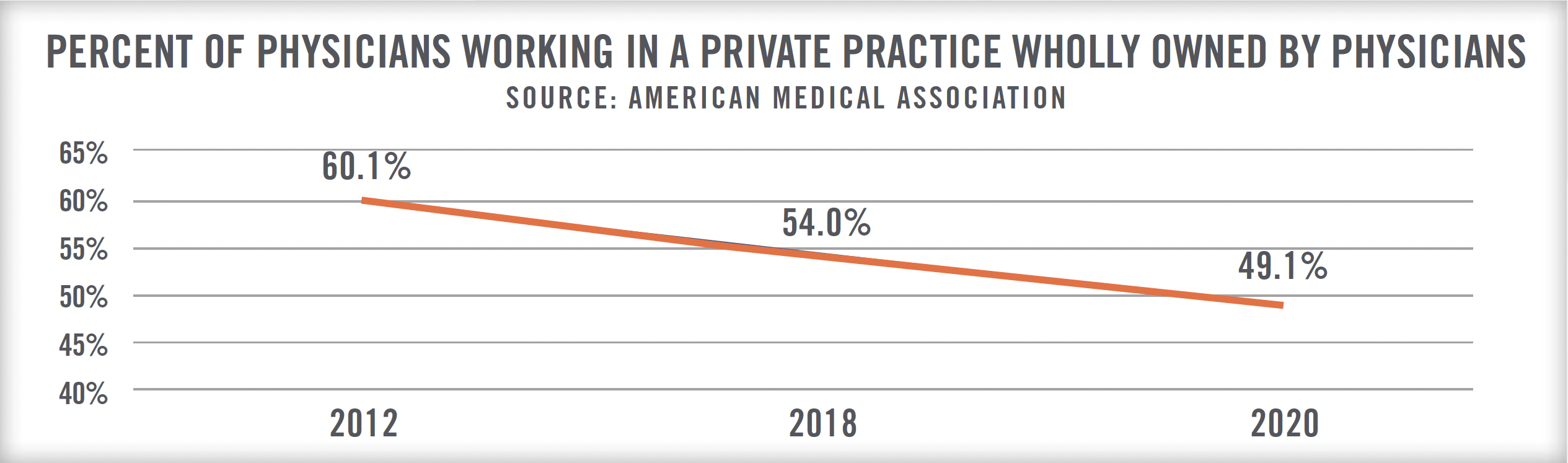

This problem is further compounded by the large portion of physician workforce that is also nearing retirement age. COVID-19 added additional strain on physicians, further accelerating the retirement of some physicians as they faced personal health risks and declining income due to loss of revenue and higher costs to acquire supplies such as personal protective equipment. Of 3,500 doctors surveyed by The Physicians Foundation between July 15 and July 26, 2020, 8 percent of physicians have closed their practices as a result of COVID-19, and 72 percent of physicians have experienced a reduction in income due to COVID-19.[1] Even before COVID-19, reimbursement pressure and need for capital to acquire new technology such as electronic health records and telemedicine software, have led physicians to sell their practices and become employees of larger organizations. According to the AMA, 2020 was the first year in which less than half of patient care physicians worked in a practice wholly owned by physicians.[2]

For many years, physician practice acquisitions were completed by hospitals and health systems, as they sought to develop strong physician relationships that allowed them to provide specialized care as well as increase their market share. Hospitals also found a need to employ physicians as retiring independent physicians left gaps in care in rural areas. From an independent physician’s perspective, government and insurer payment policies have favored larger health systems which put them at a competitive disadvantage. Many of these practices were struggling due to administrative and regulatory burdens such as measuring and reporting quality metrics and needing to implement capital intensive electronic health record systems. Combined with reimbursement cuts to certain specialties, failure to maintain reporting and minimum quality goals also resulted in reimbursement penalties. Independent physicians were also dealing with a change in consumer expectations, which include the need for convenience, use of technology for scheduling appointments, rapid test results on mobile devices, virtual communication, and use of telemedicine. Furthermore, younger physicians usually have high student loan burdens and seek financial stability and work-life balance. These trends have all contributed to physicians seeking to be employed instead of pursuing private practice.

Hospitals have not been the only ones acquiring medical practices. Non-traditional industry participants like insurance/health plans, private equity firms, large employers (e.g., Amazon and Apple), and Medicare Advantage focused providers have also started investing in physician practices causing an arms race in securing the services of healthcare providers. These non-traditional players still provide benefits including access to capital, reduced administrative burdens, practice management services, and contracting leverage, but can offer other benefits such as potential equity payouts or the ability to innovate and influence new models of care and technology.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A. INSURANCE COMPANIES

Insurance companies and health plans have been acquiring physician practices as a way to vertically integrate. The motivations behind these transactions are different than the acquisitions made by health systems, and are primarily driven by goals of controlling spending, lowering cost, and increasing quality through managing care and reducing costly/wasteful utilization. Furthermore, these transactions highlight the need for health data to further optimize care and impact health outcomes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

B. PRIVATE EQUITY

In the early 1990’s, physician practice management companies (“PPMCs”) grew quickly as the industry saw the need for consolidation in order to achieve economies of scale as well as the size necessary to negotiate managed care contracts. As physicians began looking for partners with capital and organizational expertise, PPMCs aggressively acquired single and multi-specialty groups and offered a way for physicians to remain independent from hospitals. At the peak, there were over 39 publicly traded PPMCs, with companies such as MedPartners, PhyCor and FPA Medical Management having thousands of affiliated physicians. Due to the unsustainable prices being paid for acquisitions, followed by underperforming assets, PPMCs collapsed as quick as they rose, with eight of the ten largest publicly traded PPMCs declaring bankruptcy by 2002. Nearly two decades later, many of the challenges that PPMCs attempted to solve still exist and have grown in complexity. As a result, we are now experiencing the second generation of PPMCs. The industry still remains highly fragmented, and projected healthcare spending is expected to continue increasing. Similar to the early 1990’s, private equity activity has ramped up quickly. In 2014, only 10 percent of physician medical group deals were done by private equity firms, which has since grown to 72 percent in 2020. This proportion of private equity transactions seems likely to continue as the amount of private equity capital available for investment has approached nearly $1.9 trillion globally.[4]

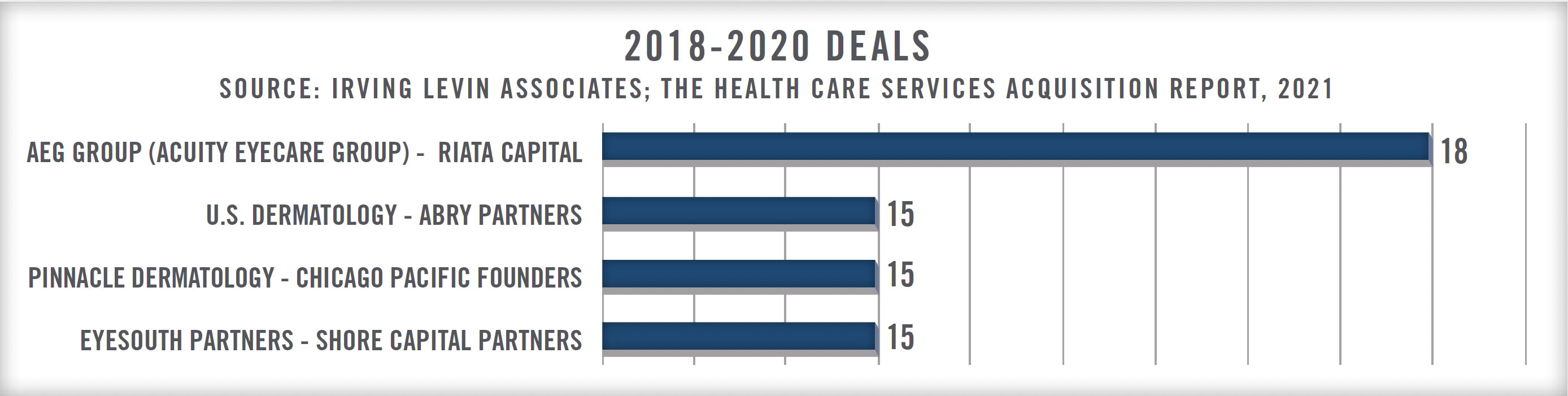

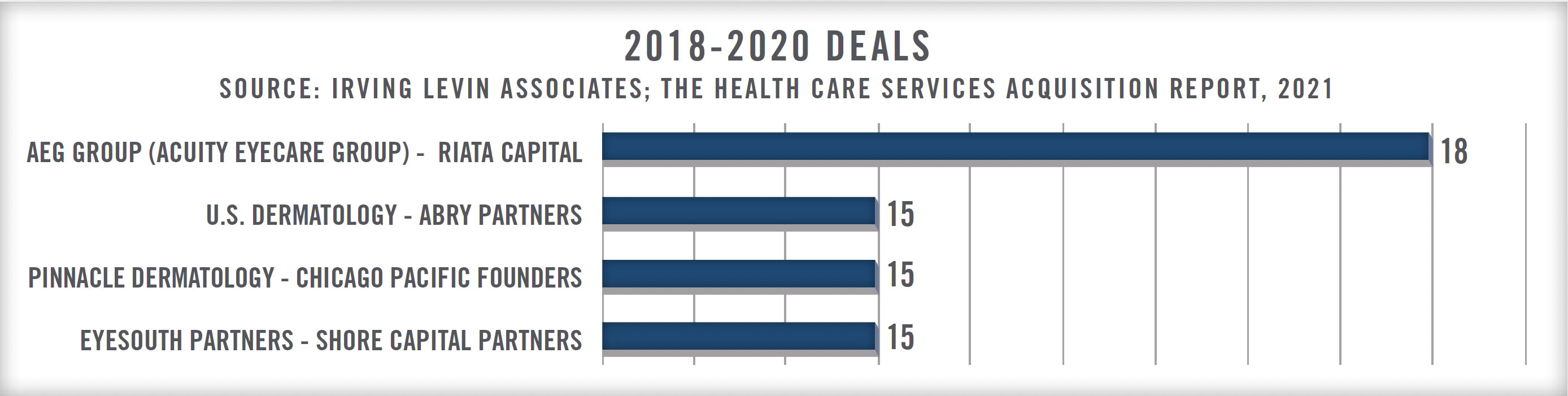

What started as a consolidation of practices focused on hospital-based specialties such as emergency medicine, radiology, and anesthesiology, has since moved on to medical specialties such as ophthalmology and dermatology which generate more reimbursement from private insurance and out-of-pocket payments, rather than government payors. Between 2018-2020, the most active private equity backed platform companies were focused on these two specialties.

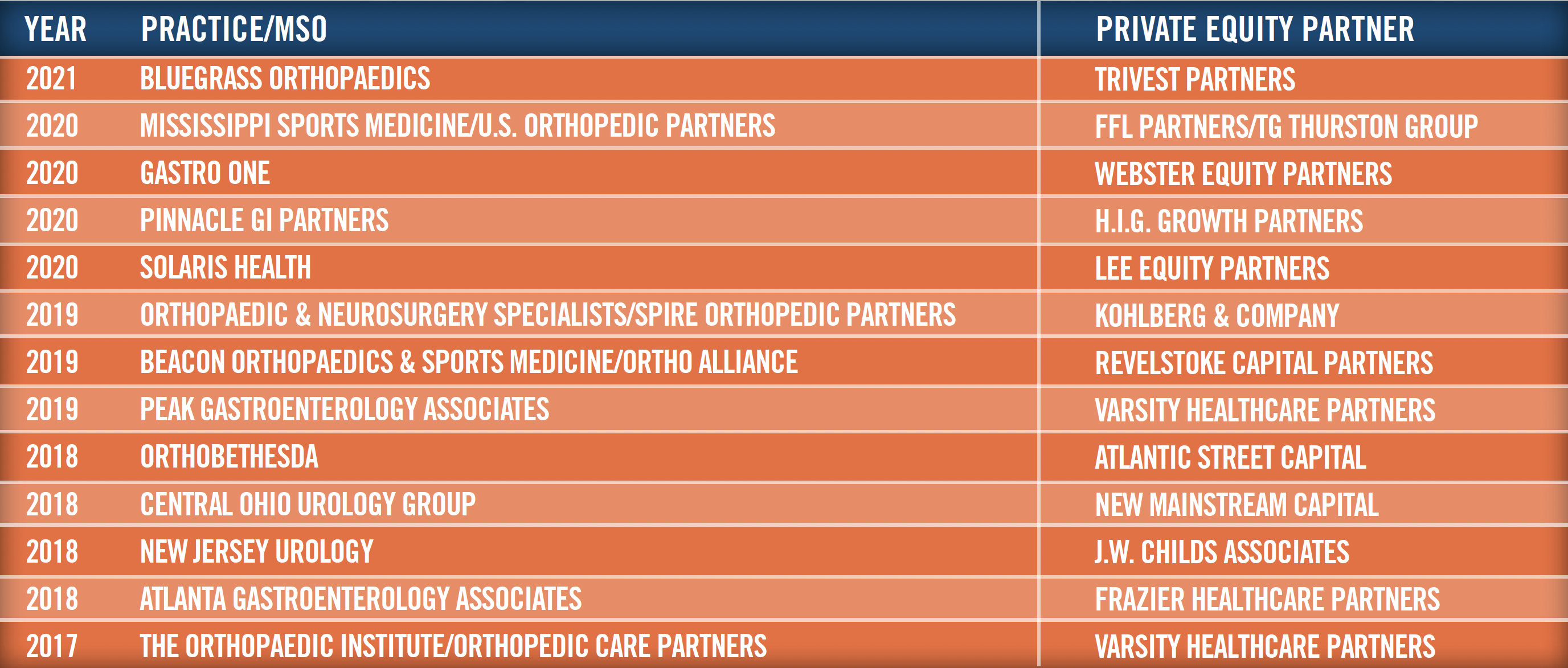

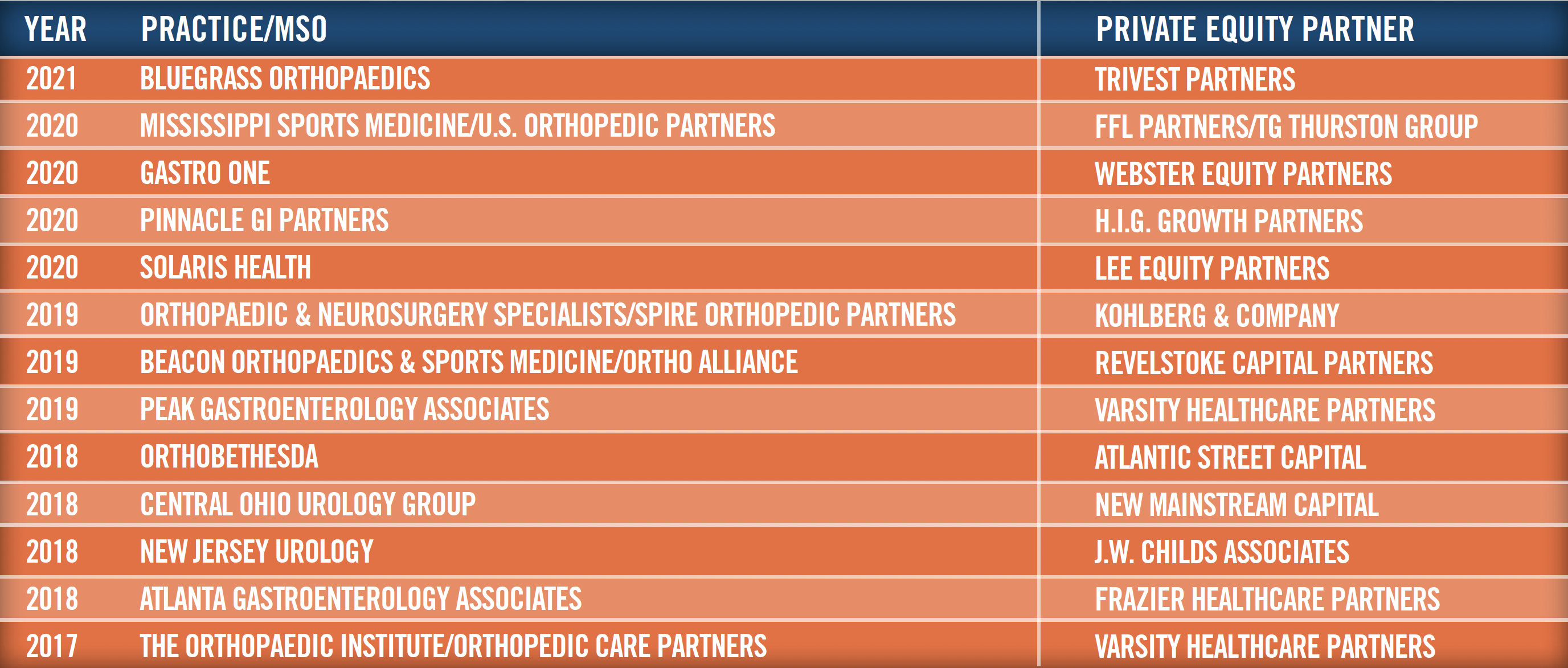

Private equity firms are now shifting to medical specialties such as orthopedics, gastroenterology, and urology which can generate ancillary revenue from ambulatory surgery centers, medical imaging, pharmacy, pathology, physical therapy, and durable medical equipment. Furthermore, there are trends that suggests continued growth in these specialties such as earlier colorectal screenings and a generation that desires to maintain an active lifestyle later into life. The number of total joint surgeries continues to increase as advances in technologies and surgical procedures have allowed these surgeries to be performed on an outpatient basis and in freestanding ambulatory surgery centers.

C. INDEPENDENT PHYSICIAN GROUPS

In a 2019 survey conducted by McKinsey & Company, 79 percent of small independent practices and 67 percent of large independent practices cited autonomy as a top factor in selecting their current practice model.[5] The main challenges faced by independent physicians are clinical integration, increasing administrative burden, and the need for negotiating power. One option for a solo practitioner or small practice is to join a larger physician-owned medical group which usually brings stronger brand awareness, economies of scale, and the resources to manage the administrative tasks associate with running a practice.

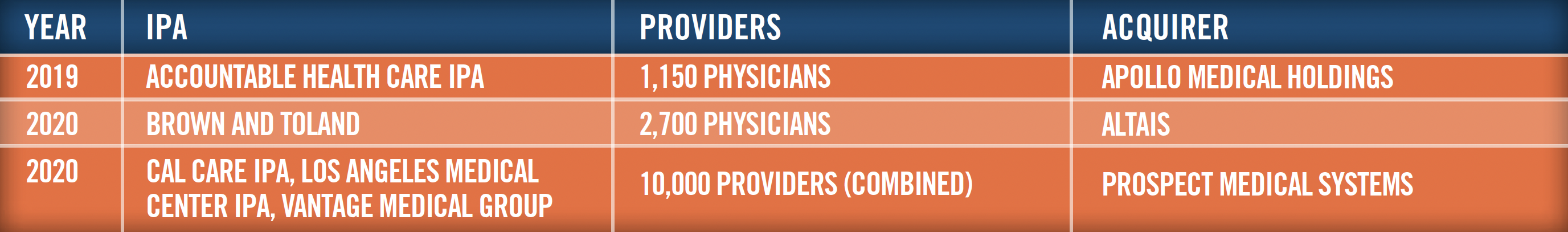

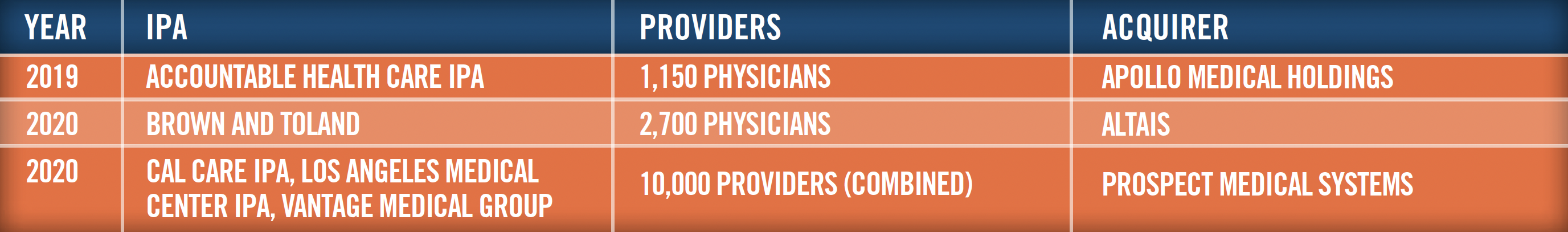

Another alternative for independent physicians is to form and/or join an independent physician association (“IPA”). An IPA is a separate business entity owned by a network of physician practices with the goal of using its size and scale to reduce overhead and negotiate managed care contracts. Physicians who join an IPA are still able to operate independently from other members of the IPA. IPAs may still face challenges as it is difficult to gain cooperation from large numbers of physicians. Some payors will compensate IPAs through capitated contracts which puts the financial risk on the IPA. Under these contracts, an IPA receives a flat per member, per month payment regardless of the how much a patient utilizes healthcare services. If these risks are not properly managed, IPAs can incur significant losses.

The need for capital still exists for IPAs, which is evident in recent IPA transactions. The partnership between Altais and Brown and Toland highlights the market demand for robust practice management platforms that provide advanced data tools. With health systems and medical groups looking to expand their networks, there will be continued transaction activity in this space.

D. LARGE EMPLOYERS

Nearly 50 percent of Americans are covered under an employer sponsored health plan, with 84 percent of large firms being self-funded.[6] With employers focusing on reducing costs and improving employee satisfaction, there is a strong incentive for employers to provide access to convenient and high-quality healthcare in order to drive better clinical and financial results. Increased employee wellness through preventative healthcare can further reduce loss of employee work hours. Large companies have started exploring different models to ensure their employees have access to high quality healthcare.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

E. MEDICARE ADVANTAGE FOCUSED PROVIDERS

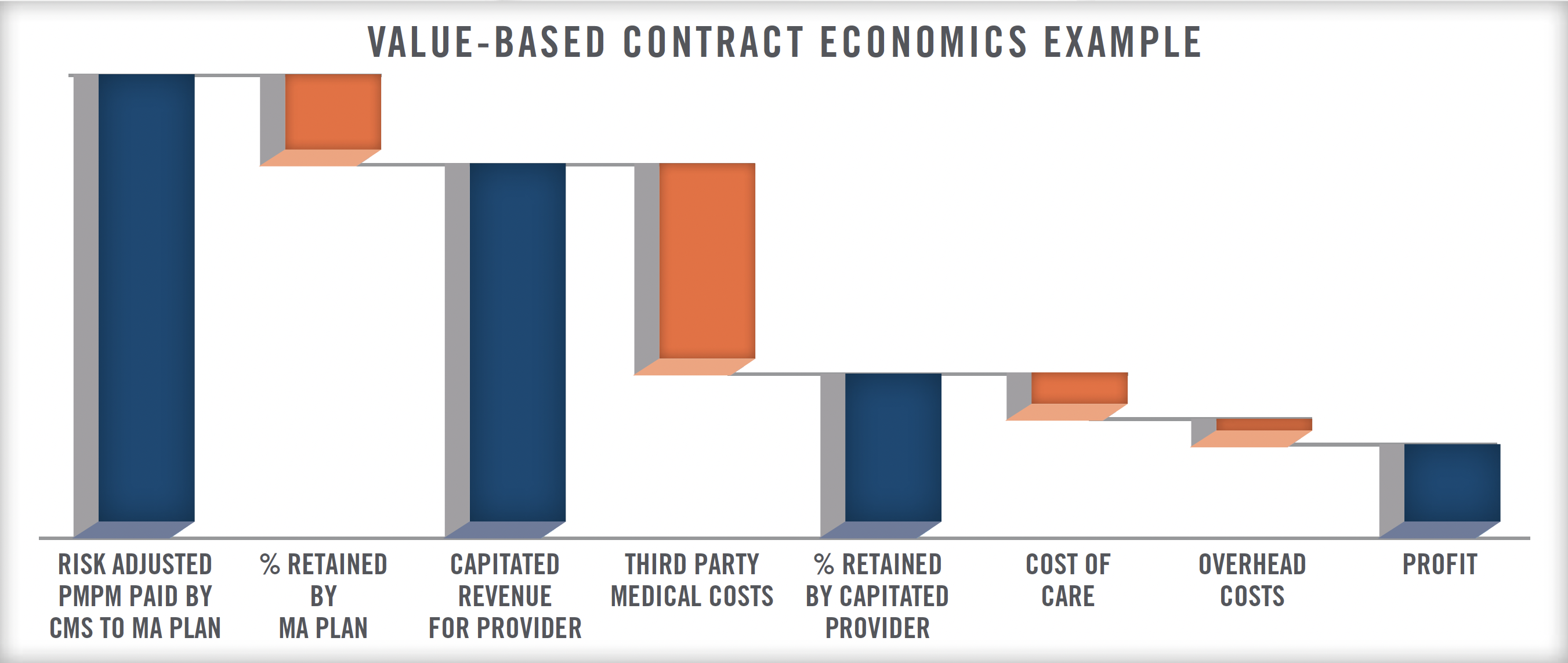

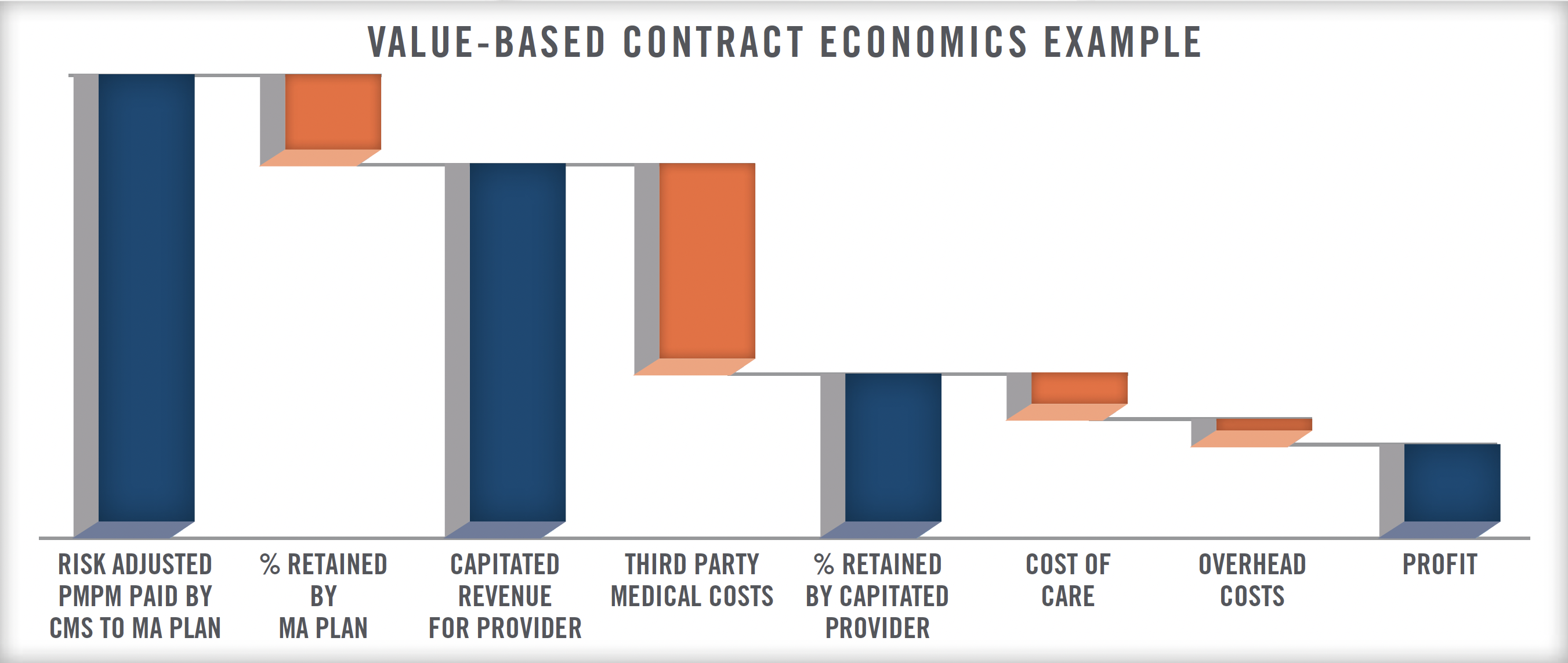

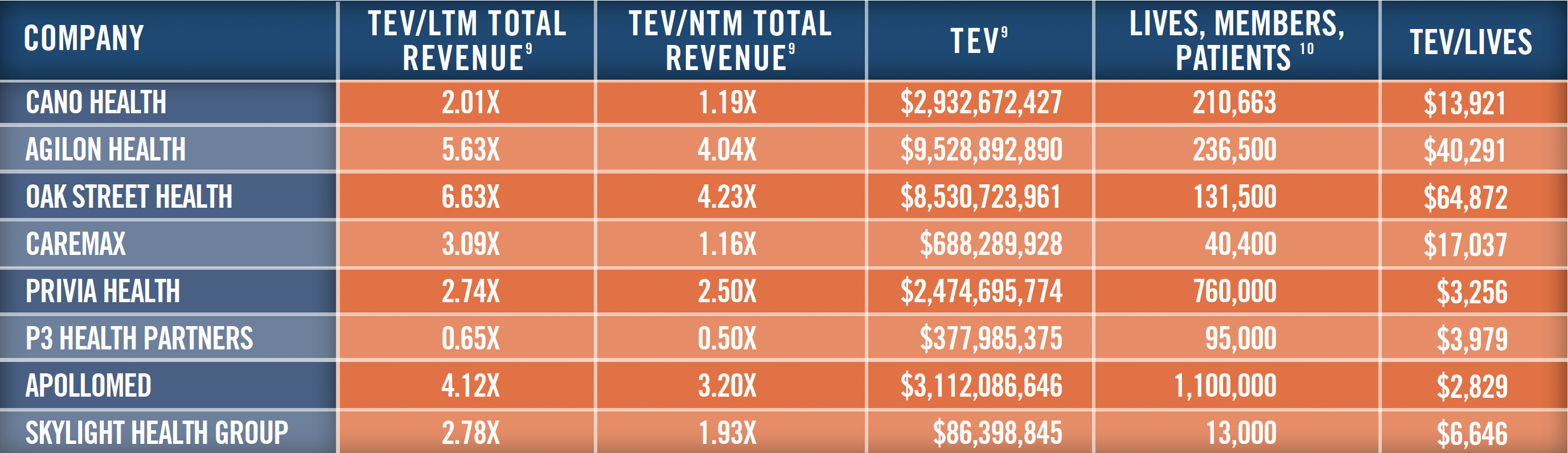

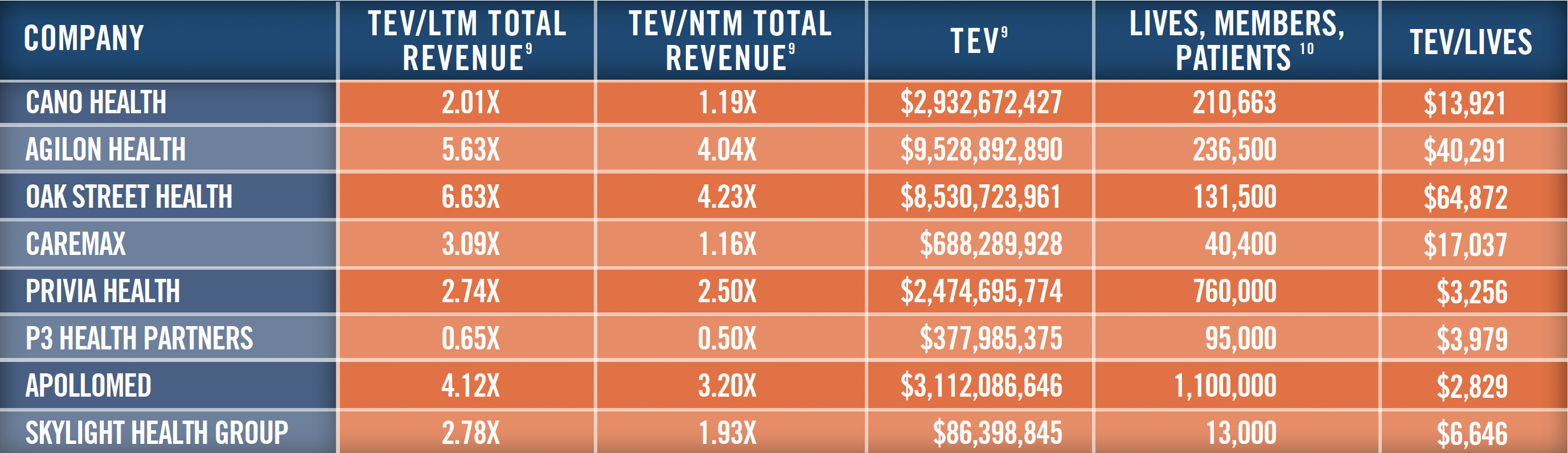

With the continued increase in population eligible for Medicare/Medicare Advantage, certain providers such as Cano Health (NYSE: CANO), Agilon Health (NYSE: AGL), Oak Street Health (NYSE: OSH), and CareMax (NASDAQ: CMAX) have focused on providing care to this segment of the population. These companies provide care through globally capitated or full-risk contracts and receive a pre-negotiated per member, per month payment. Through use of their technology-powered population health platforms, these companies are rewarded for furthering the “triple aims” of improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of healthcare services.

While the companies outlined above are focused on healthcare for seniors, they are a part of the greater “physician enablement” market which also includes companies such as VillageMD, Privia Health (NASDAQ: PRVA), Aledade, ChenMed, P3 HealthPartners (NASDAQ: PIII), ApolloMed (NASDAQ: AMEH), and Skylight Health Group (TSXV: SLHG). Though each of these companies have slightly different models and serve different populations, they all share a similar vision of providing physicians with the tools and technology necessary for succeeding in value-based care.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Health Systems

In most physician practice transactions, health systems acquire tangible and intangible assets of a practice and subsequently enter into an employment/professional services arrangement with the physicians. Physicians generally receive a base salary with the opportunity to earn production-based compensation (commonly measured based on work relative value units) which must be consistent with fair market value. While this provides physicians with stable compensation and the ability to focus on patient care, they are precluded from having equity in the practice entity and therefore are not able to benefit from any growth of the business. In recent years, hospital-employed physicians have been offered investment opportunities in ambulatory surgery centers that are co-owned by their hospital employer. On April 26, 2021, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General issued a favorable advisory opinion regarding the investment in a new ambulatory surgery center that would be owned jointly by a health system, management company, and various physician investors employed by the health system.[11] Though less common, these types of arrangements can be structured to be compliant with federal and state laws.

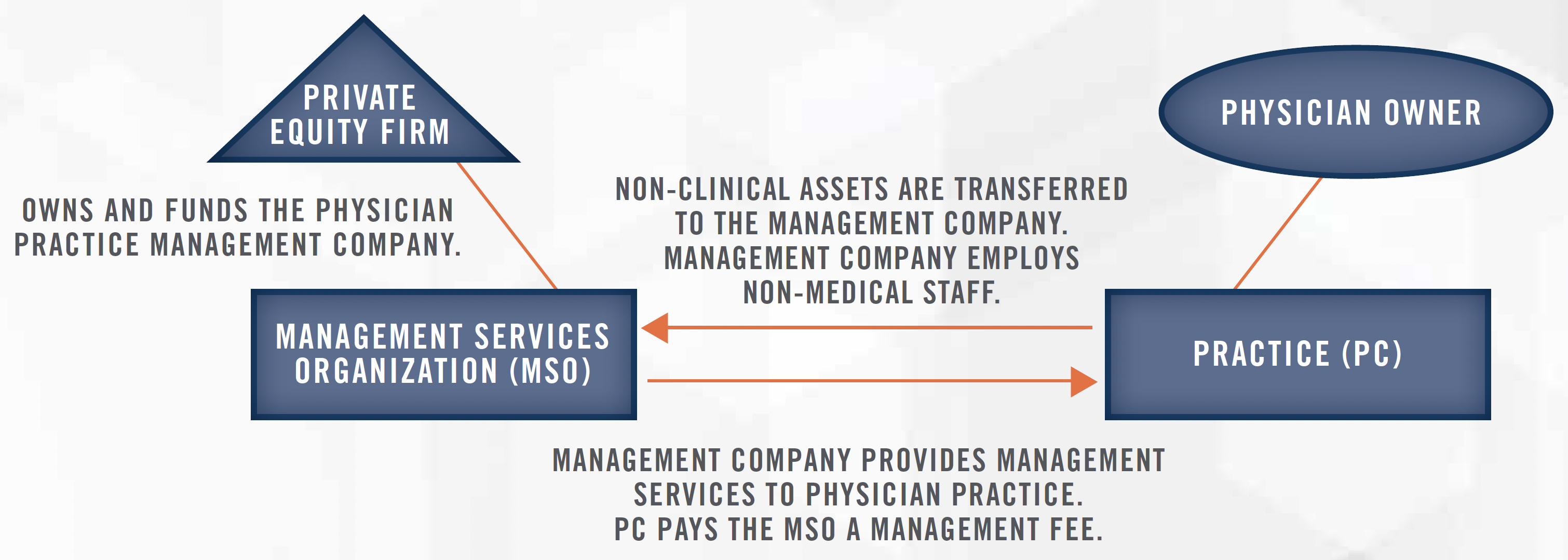

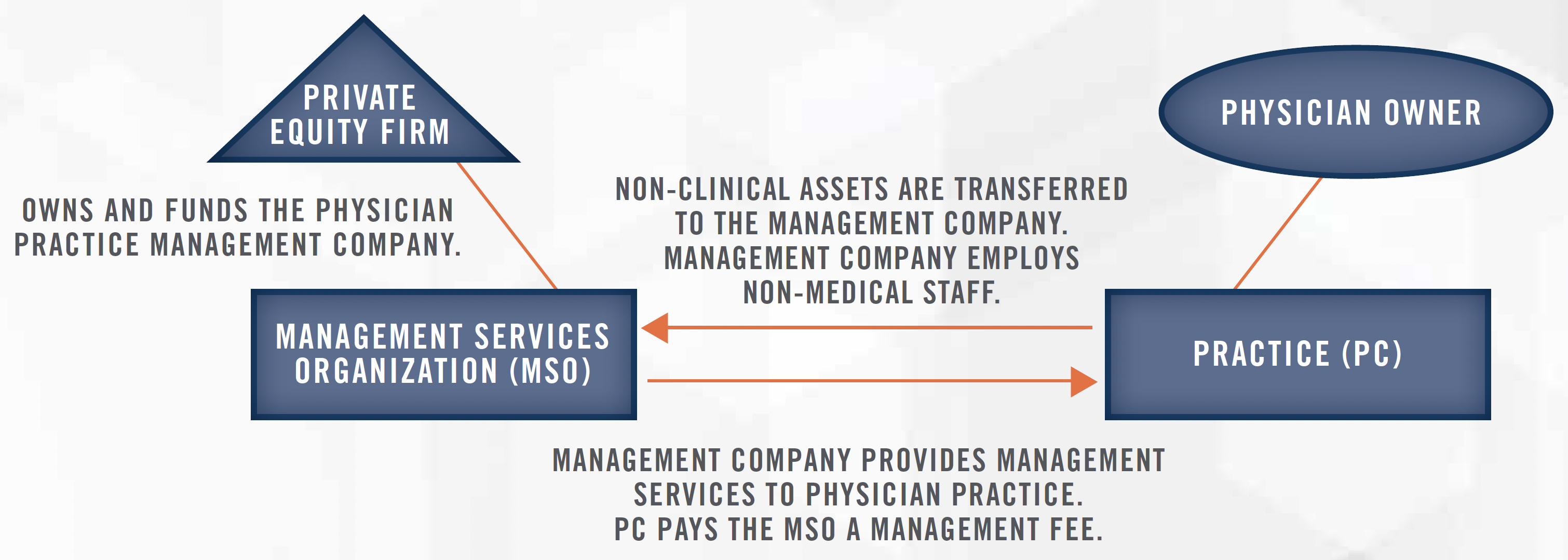

Private Equity

Private equity firms are prohibited from owning physician practices in many states due to corporate practice of medicine (“CPOM”) laws. Therefore, these transactions typically involve the private equity firm establishing a PPMC which acquires the non-clinical assets, business functions, and ancillary services of a medical group. These medical groups are often large “platform” practices that have a substantial market share and a strong reputation. Subsequently, the PPMC provides management services to the medical practice, owned by licensed physicians, in exchange for a fair market value management fee.

Shareholder physicians receive an upfront cash payment as well as rollover equity in the PPMC. This helps align the interest of the shareholder physicians as it allows for the prospect of a future payout when the private equity firm sells to another buyer (usually after five to ten years). The shareholder physicians generally pay for their equity interest by taking a 20 percent to 30 percent cut in their compensation. The private equity firm then grows the value of the medical group by acquiring additional small and solo practices or “add-on” practices to merge with the larger “platform” practice.

Private equity firms benefit in being less constrained by the legal and regulatory requirements compared to health systems, but still need to be cognizant of CPOM laws, fee splitting, as well as anti-kickback laws. An overview of these regulations is discussed in the following section.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

CPOM laws prohibit non-physicians from owning or controlling physician practices or employing physicians. While each state has its own laws, they can generally be categorized as either “strong” or “weak”. In “strong states” non-professional corporations cannot hire physicians without meeting a specific exception set forth in the CPOM laws. “Weak” states may allow non-professional corporations, such as hospitals, to employ physicians if the licensed physicians maintain actual control over clinical decision-making. While CPOM laws may dictate how a physician practice transaction is structured, investors must also be aware of various fraud and abuse laws that may impact the structure of certain compensation arrangements such as managements fees.

The prohibition on fee splitting is aimed at situations where a healthcare professional splits part of the professional fee from treating a referred patient with the source of the referral. This is relevant to PPMC arrangements as it may require that a management fee between the PPMC and the professional practice to be structured as a fixed fee instead of a percentage of revenue. Furthermore, it’s important that these management fees are consistent with fair market value. Unlike health systems who have to ensure acquisitions and compensation arrangements with physicians are consistent with fair market value, private equity firms are primarily concerned with making sure their management arrangements are structured to be compliant with state and federal anti-kickback laws.

Lastly, when evaluating a potential transaction, a buyer may require certain data to perform its due diligence and understand the financial impacts of the transaction. Buyers and sellers should be aware of federal antitrust laws that prevent the parties from freely sharing agreements with third party payors.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The physician practice industry has experienced significant changes over recent years and faces a growing list of challenges surrounding increasing administrative burden and continued reimbursement pressures. At the same time, there is a shortage of physicians while demand continues to increase. To be able to continue focusing on caring for their patients, physicians have realized the need to partner with other organizations, whether it be with other independent physicians or entities such as private equity investors. The authors of this article have significant experience in providing valuation and consulting services for physician practice transactions. Given the continually changing regulatory environment, it’s important to rely on an appraiser that understands the details of these types of transactions.

David Y. Lo, CFA, ASA is a Director in our Denver office. David can be reached at (303) 566-3195 or DLo@hcfmv.com. Nicholas J. Janiga, ASA is a Partner in our Denver office. Nick can be reached at (303) 688-0700 or NJaniga@hcfmv.com.

[1] The Physicians Foundation, “2020 Survey of America’s Physicians”, last accessed on March 29, 2021, from: https://physiciansfoundation.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/08/20-1278-Merritt-Hawkins-2020-Physicians-Foundation-Survey.6.pdf

[2] American Medical Association, “Recent Changes in Physician Practice Arrangements: Private Practice Dropped to Less than 50 Percent of Physicians in 2020”, from: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-05/2020-prp-physician-practice-arrangements.pdf

[3] Humana, “Humana Announces Agreement to Acquire a 40 Percent Minority Interest in Kindred’s Homecare Business for Approximately $800 million through a Joint Venture with an Entity Owned by TPG Capital and Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe,” last accessed on March 29, 2021, from: https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/49071/000119312517372901/d474448dex991.htm

[4] S&P Global, “2021 Global Private Equity Outlook,” last accessed on March 29, 2021 from: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/newsinsights/research/2021-global-private-equity-outlook

[5] McKinsey & Company, “Physician employment: The path forward in the COVID-19 era”, last accessed on March 30, 2021 from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/physician-employment-the-path-forward-in-the-covid-19-era

[6] Kaiser Family Foundation, “2020 Employer Health Benefits Survey”, last accessed on March 30, 2021, from: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2020-employer-health-benefits-survey/

[7] AMA, “Direct-to-employer contracting: What doctors should know” last accessed on March 30, 2021 from: https://www.ama-assn.org/practicemanagement/payment-delivery-models/direct-employer-contracting-what-doctors-should-know

[8] Fierce Healthcare, “Amazon, Crossover Health expand employee health clinics to 2 more states” last accessed on December 20, 2021 from: https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/tech/amazon-crossover-health-expand-employee-health-clinics-to-two-more-states

[9] Data from S&P Capital IQ.

[10] Data for CANO, AGL, OSH, and CMAX from respective Form 10-Qs for the period ended September 30, 2021. Data for PRVA, PIII, AMEH, and SLGH are from respective investor presentations.

[11] OIG Advisory Opinion No. 21-02