Authors: Luis A. Argueso, Jim D. Carr, ASA, MBA and Andrew L. Worthington

![]() INTRODUCTION TO HOSPITAL-BASED CLINICAL COVERAGE ARRANGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION TO HOSPITAL-BASED CLINICAL COVERAGE ARRANGEMENTS

The Affordable Care Act has significantly altered the alignment between hospitals and clinical providers. Hospitals now have many incentives to integrate with clinicians. For example, according to a recent study by the American Medical Association, from 2012 to 2018, the number of practices with at least partial ownership by hospitals increased year over year.[1] However, enforcement of the strict rules and regulations regarding hospital compensation of clinical providers has only increased.[2] The Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statute continue to pose a myriad of pitfalls for hospitals and health systems that seek to compensate providers for their services.

Oftentimes, a healthcare facility may not wish to incur the costs involved in directly employing the clinical resources needed to staff their primarily hospital-based service lines (e.g., anesthesiology, emergency medicine, hospitalist medicine, and intensive care). In lieu of direct employment, hospitals have increasingly opted to enter into Hospital-Based Clinical Coverage Arrangements (“HBCCAs”). Because it is common for hospital-based providers to generate insufficient collections from their professional services, these arrangements usually involve a form of financial support: typically, a “collections guarantee” or a fixed “subsidy.” Under a collections guarantee payment model, a hospital will “guarantee” that a provider generates sufficient revenue to cover costs by performing regular reconciliations to pay the shortfall between the guaranteed amount and actual collections (or to have the provider refund the hospital for prior advances if revenues exceed costs). Alternatively, a subsidy payment model involves a fixed payment intended to cover the estimated shortfall between costs and estimated revenues.

While independent and local physician practices (referred to as “unaffiliated practices,” herein) are often engaged to provide the hospital-based clinical coverage, we have observed growth in the number of arrangements involving the affiliates of large, national medical groups (referred to as “affiliated practices,” herein). In recent years, companies such as TeamHealth, Envision, Vituity, SCP Health, and Sound Physicians have grown and purchased smaller physician-owned practices. They continue to enter into arrangements with hospitals to provide coverage of hospital-based service lines.

In this ever-changing landscape, there are innumerable missteps that can lead to the potential for overcompensation to physicians and medical groups for clinical services. When engaging affiliated practices of national providers as part of a HBCCA, it is common for these providers to include a portion of their corporate general and administrative expenses in the cost to provide the services, typically in the form of a management fee. Others national providers may require their affiliated practices to generate a “profit” to cover the indirect costs incurred by the corporation and to return value to their owners. This article describes how to treat such line items (e.g., management fees and profit allocations) from a Fair Market Value (“FMV”) perspective, and how to avoid the potential pitfalls that may arise from HBCCAs.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

To value HBCCAs, an asset- (a.k.a., cost-) based approach is used, whereby the valuator determines the FMV hypothetical cost for a hospital to replicate the professional service line. The collections guarantee amount is represented by this FMV cost range, while the subsidy range is calculated by offsetting the hypothetical cost level by estimated revenue from professional services. The primary costs associated with HBCCAs include: (i) physician salaries and benefits, (ii) advanced practice professional (“APP”) provider salaries and benefits, (iii) malpractice insurance premiums, and (iv) other operating expenses. Other operating expenses include consideration for administrative practice support staff, billing / collection, and/or technological infrastructure expenses. Ultimately, to remain compliant with the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statute, the collections guarantee / support payment amounts must not exceed the cost / shortfall, which a hospital would incur in providing the clinical coverage directly.

When applying a cost approach to a HBCCA the goal is to calculate a range of costs which matches the level of services required under the arrangement. This requires diligence when analyzing and selecting benchmarks for salaries, benefits, malpractice insurance, and other operating expenses.[3] For provider compensation, one should compare national data and regional data to the compensation levels common in the hospital’s marketplace, as well the productivity and time expectations an individual provider will have to deliver according to the HBCCA. Additionally, one needs to consider the appropriate cost of malpractice insurance and other operating expenses, in relation to the hospital-based service line being valued. Typically, hospital-based practices will incur lower operating expenses relative to independent office-based physicians, since they do not have to pay for occupancy, equipment, supplies, and clinical support staff (e.g., medical assistants and nurses), given that hospitals bear the cost of these items pursuant to most HBCCAs.

Practices unaffiliated with large medical groups and specializing in hospital-based services are typically structured as professional corporations. Accordingly, any “profit” generated from their services are distributed to the physician-owners. Conversely, the affiliated practices of a large national provider typically pass through any “excess” revenue to the corporate parent entity. The parent then distributes the remaining share, after removing corporate-level expenses, as profit to shareholders/ owners. This difference in how “profit” is accounted for by practice type has a significant impact on the valuation of HBCCAs.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In establishing the FMV compensation associated with HBCCAs, a valuator considers the “hypothetical provider” standard. This requires that the valuator determine the FMV compensation associated with an asset (or service arrangement) between a hypothetical willing buyer and seller.[4] In the context of HBCCAs, a hypothetical “seller” of hospital-based clinical coverage could be an employee of the hospital, or an independent contractor practice. Regardless, of the type of “seller,” the FMV compensation must match the level of service delivered by the provider. If there is no material difference in the services provided, the compensation for such services must not vary by provider type.

For HBCCAs, the largest component of “cost” to provide the services is the professional staffing compensation earned by the physicians and APPs. Accordingly, a valuator must be diligent in selecting compensation benchmarks that correspond to the level of services required of a practice under an HBCCA. When selecting compensation benchmarks for physician providers, a valuator must be aware of what is included in these “compensation” benchmarks. “Total” compensation benchmarks often include more than just a physician’s base salary For example, the Medical Group Management Association’s (“MGMA”) reported total compensation figures include: base salary, incentive payments, research stipends, honoraria and distribution of practice profits.[5] Unlike affiliated practices, unaffiliated practices typically do not generate a profit (i.e., all “excess” income above costs is typically distributed to the physician owners). More specifically, MGMA defines their benchmarks for total compensation, “as the direct compensation amount individually reported on a W2, 1099 or K1 tax form,” emphasis added. The Schedule K-1 tax form reports the share of earnings of a partner in a business partnership (such as a physician practice). Therefore, when matching compensation benchmarks, it is important to note that the compensation amounts at higher percentiles may include income that is attributable to a physician partner’s ownership in a medical practice.

This “ownership income” hypothetically represents the payment to a physician-partner for the business risk inherit in operating a medical practice. All else being equal, one may argue that a physician-partner is entitled to higher compensation than an employed physician for the same level of clinical coverage, since the physician-partner is subject to the risk that his or her income may be reduced if the practice generates a loss. Conversely, affiliated practices often “outsource” the management of the business to the corporate owner, which employs the staff and resources needed to effectively run the practice. For such affiliated practices, it is common for the corporate parent to allocate a “management fee” or “required profit margin” to the income statement of the practice, in order to represent the value of the owner’s risk in the practice. As a result, a valuator must be wary that the sum of the management fee, profit margin and physician compensation does not result in a scenario where the income from ownership is double-counted.

When reviewing the allocated “management fees” and “profit margins,” we have observed that these values can represent various items, depending on the party involved. For example, a management fee or profit margin may include both: (i) an allocation of the pro-rata share of a corporate entity’s staff and resources involved in operating the affiliated practice, and (ii) profit from the business risk of operating the practice. Alternatively, an affiliated practice may have both management fee and profit margin line items on their income statements.

In contrast, unaffiliated practices will bear all costs and their partners “earn” the “profit” associated with the services provided by the medical group. As mentioned above, profits are typically distributed to the physician-partners. For these unaffiliated practices, management costs typically allocated by a corporate parent to affiliated practices instead appear on the income statement of unaffiliated practices as an operating expense (e.g., practice administrator salaries and professional services payments to billing and collecting agencies). In summary, if the level of services provided are the same, the ultimate revenue earned by affiliated and unaffiliated practices must be similar, though the distribution of the revenue between the affiliated practice and corporate parent may vary.

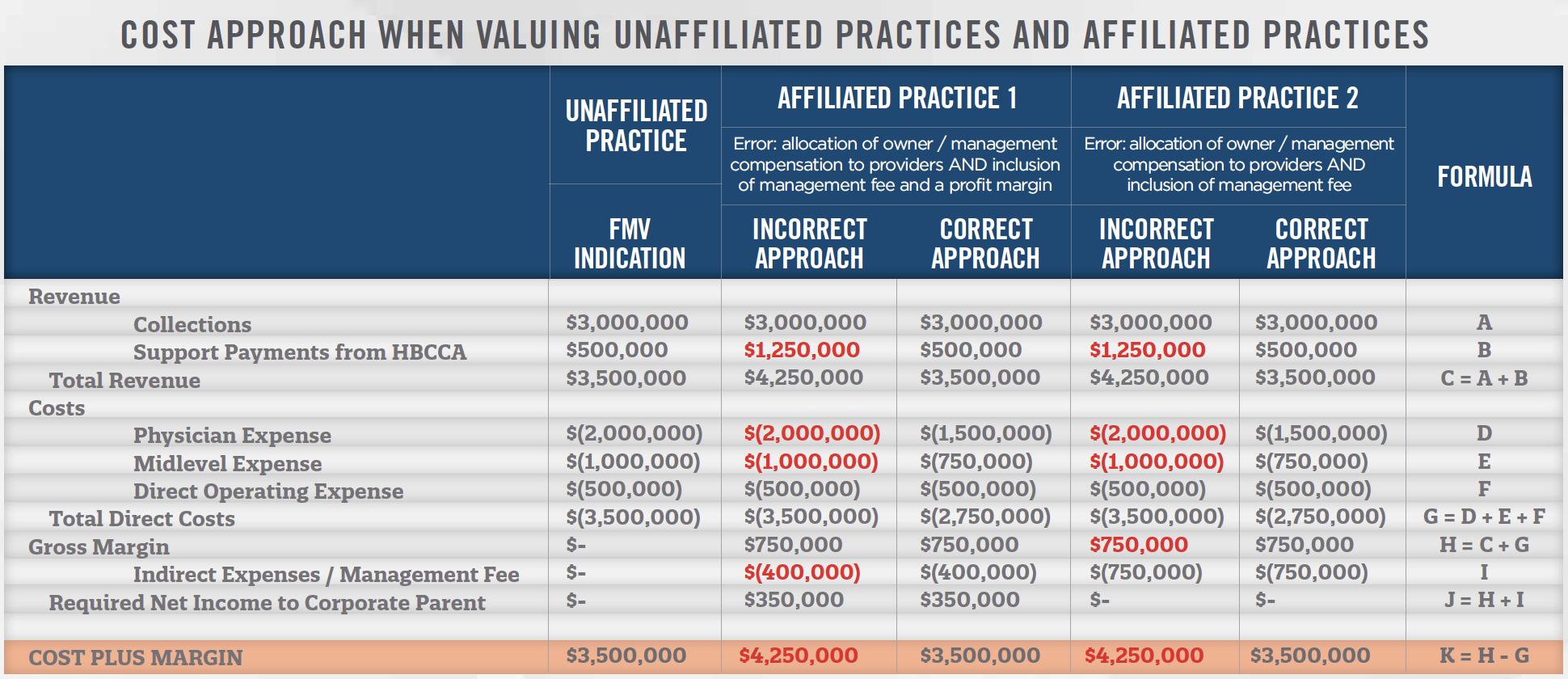

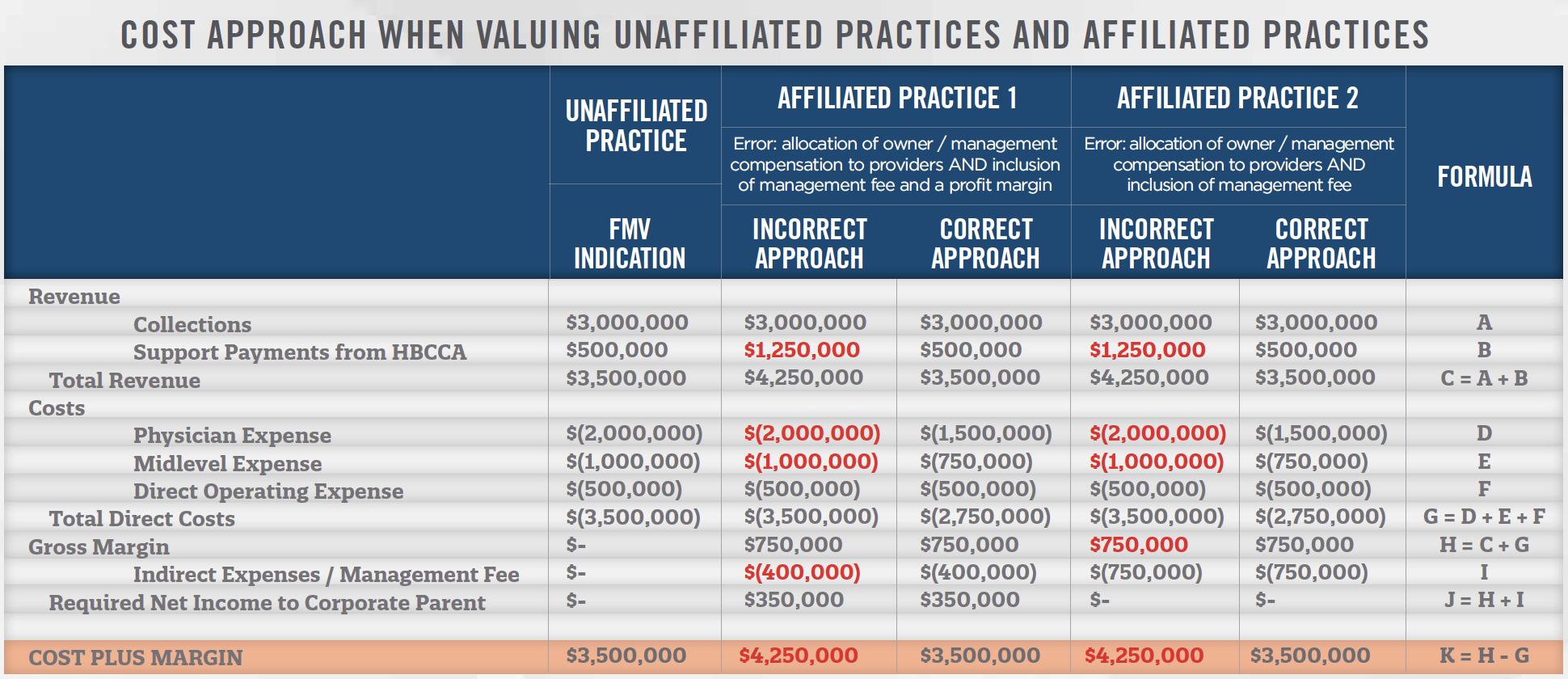

To provide a clear illustration of the principles discussed above, we have prepared three summary income statements for: (i) an unaffiliated practice (“Unaffiliated Practice”), (ii) an affiliated practice whose corporate parent allocated a profit margin and management fee (“Affiliated Practice 1”), and (iii) an affiliated practice whose parent only allocated a management fee intended to cover both costs and profit (“Affiliated Practice 2”). The summary statements are shown below.

As illustrated above, the Unaffiliated Practice attributes all excess revenues above cost to its physician owners in the form of distributions (i.e., physician compensation). When the correct cost approach is applied to the affiliated practices (i.e., when management fees and profit margins are components of an income statement), provider compensation is reduced (reflecting the shifting of costs and/or risks to the corporate parent), thus resulting in a “cost plus margin” amount that is the same as with the Unaffiliated Practice.

In the table above, the physicians and APPs of the Unaffiliated Practice participate in the management of the group by overseeing quality and performing administrative functions, and are at risk for their total compensation. These activities entitle them to “owner compensation.” In the incorrect approach used to establish costs for Affiliated Practices 1 and 2, these management tasks are performed by the corporate parent, while the physicians and advanced practice providers are guaranteed their salaries. Management fees are paid to the corporate parent for both practices and a profit margin is allocated to the shareholders for Affiliated Practice 1. However, because these providers neither bear the risk of financial loss, nor participate in the management of the practice, the incorrect approach errs in ascribing compensation equal to that of the Unaffiliated Practice providers. As a result, the support payments pursuant to the HBCCAs for Affiliated Practices 1 and 2 exceed the FMV level of financial support. The incorrect income statement line-items are presented in red text.

The primary pitfall that can put hospitals and health systems in legal danger is utilizing high physician compensation benchmarks (which may include physician-owner profit distributions), and including additional consideration for practice profit (or management fees which include a profit margin). In such an instance, the total revenue to the practice may exceed the FMV cost to provide the services, inclusive of a profit margin which is reflected in the physician compensation benchmark used.

The value proposition of engaging with large national practices, is that they are able to achieve cost savings and improved quality through economies of scale. For example, Mednax, Inc. claims a competitive advantage over other providers because: (i) it has access to its clinical research and data from all of its affiliated practices; (ii) its ability to acquire other physician practices; and (iii) its ability to acquire complementary services lines, such as telemedicine and teleradiology services.[6] While this is only one example, it is apparent that large national practices have the ability to lower their operating costs due to their size. Accordingly, due to their ability to lower costs and achieve improved outcomes, these national practices often allocate management fees and profit margins to their affiliated practices.

However, by adding in these additional fees and profit margins, there is a risk of creating a scenario whereby the cost to the hospital of engaging a national corporate provider in a HBCCA exceeds that of a local independent practice delivering the same level of service.

As shown in the table above, the incorrect approaches for Affiliated Practices 1 and 2 did not adjust the provider compensation downwards to account for the fact that the corporate parent is bearing the risk of financial outcomes and incurring the costs to manage and operate the practice. As a result, a hospital must be cautious that the sum of direct practice expenses (i.e., including physician compensation), indirect expenses, and profit margins do not inadvertently double count any of the aforementioned components of cost. Affiliated Practices 1 and 2 exceeded the FMV revenue for the services by $750,000 since they did not correctly adjust the provider compensation levels.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

HBCCAs will continue to serve as an essential tool in securing coverage of key service lines at hospitals. The growth of affiliated practices affords hospitals the opportunity to consider alternatives to local practices or employment to secure this clinical coverage. Nevertheless, a hospital must be diligent when compensating affiliated practices to ensure all financial support is consistent with FMV. Due to differing methods of accounting for costs and profit, this process requires considering the appropriate compensation benchmarks relative to the level of service being delivered.

You may also be interested in reading our 2021 Review & Benchmarking Guide: Trends and Data Insights for Hospital-Based Clinical Coverage Arrangements.

[1] According to the AMA, 23.4% of physician practices had at least some hospital ownership in 2012, while the corresponding percentage in 2018 was 26.7%. Source: Kane, Carol K. “Updated Data on Physician Practice Arrangements: Physician Ownership Drops Below 50 Percent.” Policy Research Perspectives. American Medical Association. Accessed on December 20, 2020 from: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-07/prp-fewer-owners-benchmarksurvey- 2018.pdf

[2] From federal fiscal year 2010 to 2019, the number of investigations started undertaken by the Office of the Inspector General increased from 1,997 to 2,314, or roughly 16% over the ten-year period. Source: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees for Fiscal Years 2021 and 2012.

[3] For reference, MGMA’s Cost and Revenue Report, defines operating costs as: information technology, drug, medical, and surgical supplies, building and occupancy and their depreciation, furniture and equipment and their depreciation, administrative supplies, legal and consulting fees, promotion and marketing, ancillary services, billing and collecting expenses, and management fees.

[4] This observation is drawn from the definition of “FMV.” For more information regarding the components of the definition of FMV, refer to the International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms, jointly developed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, American Society of Appraisers, the Canadian Institute of Chartered Business Valuators, the National Association of Certified Valuation Analysts, and the Institute of Business Appraisers.

[5] See the following webpage for more details. https://www.mgma.com/MGMA/media/files/data/1910-D03338D-State-Salary-Participation_Guide-MA_v9.pdf [See pages 9 and 10 of 51]

[6] Mednax, INC. (2020). 2019 Form 10-K for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2019. Retrieved from www.sec.gov