Authors: Landon Forsythe and Jamie McIntyre, JD

A growing interest in hospital-provider alignment, coupled with the desire to establish meaningful mechanisms for provider accountability related to hospital quality, efficiency, and patient outcomes, were the original – and remain – the impetus behind service line co-management arrangements. Service line co-management arrangements are generally considered higher risk in comparison to certain other alignment structures such as medical directorships, foundation models, or direct physician employment because they may implicate (among other regulatory schemes) each of the “big three” legal considerations in healthcare; the federal Stark Law, the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS), and the Civil Monetary Penalties (CMP) Law. Structured properly, service line co-management arrangements can serve not only as effective drivers of hospital-physician alignment, but also lay the foundations for participation and success in cost savings endeavors, alternative payment models (APMs), broader clinical integration, and the delivery of value-based care.

Necessarily, service line co-management involves physicians that are part of a hospital or health system’s medical staff and in a unique position of possessing the institutional knowledge and administrative acumen and experience regarding the subject population to drive outcomes and effectively stand in the shoes of an operator. To that end, compliance with the Stark Law is a precursory gauge of comanagement as a viable alignment option. The widespread application and reaffirmation of the ‘one purpose test’ – in particular, after clarifications made by Congress in connection with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) in 2010[1] – can likewise pose a precarious circumstance for proposed co-management arrangements, many of which do not qualify for an existing AKS Safe Harbor. The incorporation of efficiency metrics and propensity for service line co-management incentives to focus, either directly or indirectly, on curbing overutilization, limiting unnecessary services, streamlining processes of care, and avoiding costly outcomes, can implicate CMP on the grounds that these initiatives may induce physicians to alter their practice patterns or shift behaviors in such a way that may reduce or limit services in comparison to historical practices.

Indeed, the OIG detailed potential CMP concerns in the context of service line co-management in its Advisory Opinion 12-22[2]. The arrangement that was the subject of AO 12-22 incorporated cost containment incentives; given the inherent perceived risks of service line co-management, the overlay of incentives focused on cost was something rarely seen at that point in time. Noting a combination of thoughtful safeties and active monitoring mechanisms to audit clinical appropriateness, preserve physician access to a full range of supplies and devices, track related adverse outcomes, and ensure against undue limitations on providers’ clinical judgment or decision making, the OIG opined that the cost-related performance features of the arrangement were structured in such a way that adequately safeguarded against sanctionable violations of the CMP. Separately, in April 2015, the passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) afforded a broader runway for certain gainsharing arrangements[3] with the addition of “medically necessary” to the provisions of the Gainsharing CMP pertinent to stinting on care. Although the narrowing of the Gainsharing CMP may not have specifically contemplated cost containment in the context of service line co-management, direct and indirect cost-focused co-management incentives have continued to grow in popularity since the passage of MACRA.

Amid increasing financial pressures and the evolution of iterative alternative payment models, hospitals and health systems around the country leveraged service line co-management to drive the success of internal initiatives and facilitate participation in novel payor programs and specific innovation endeavors, such as the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative and Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. Even where service line co-management was not intentionally deployed as a precursor to, or in explicit preparation for, future value-based or APM-centered initiatives, the features and characteristics inherent to successful co-management arrangements have been noted as distinguishing factors among high and low performers in value-based programs.

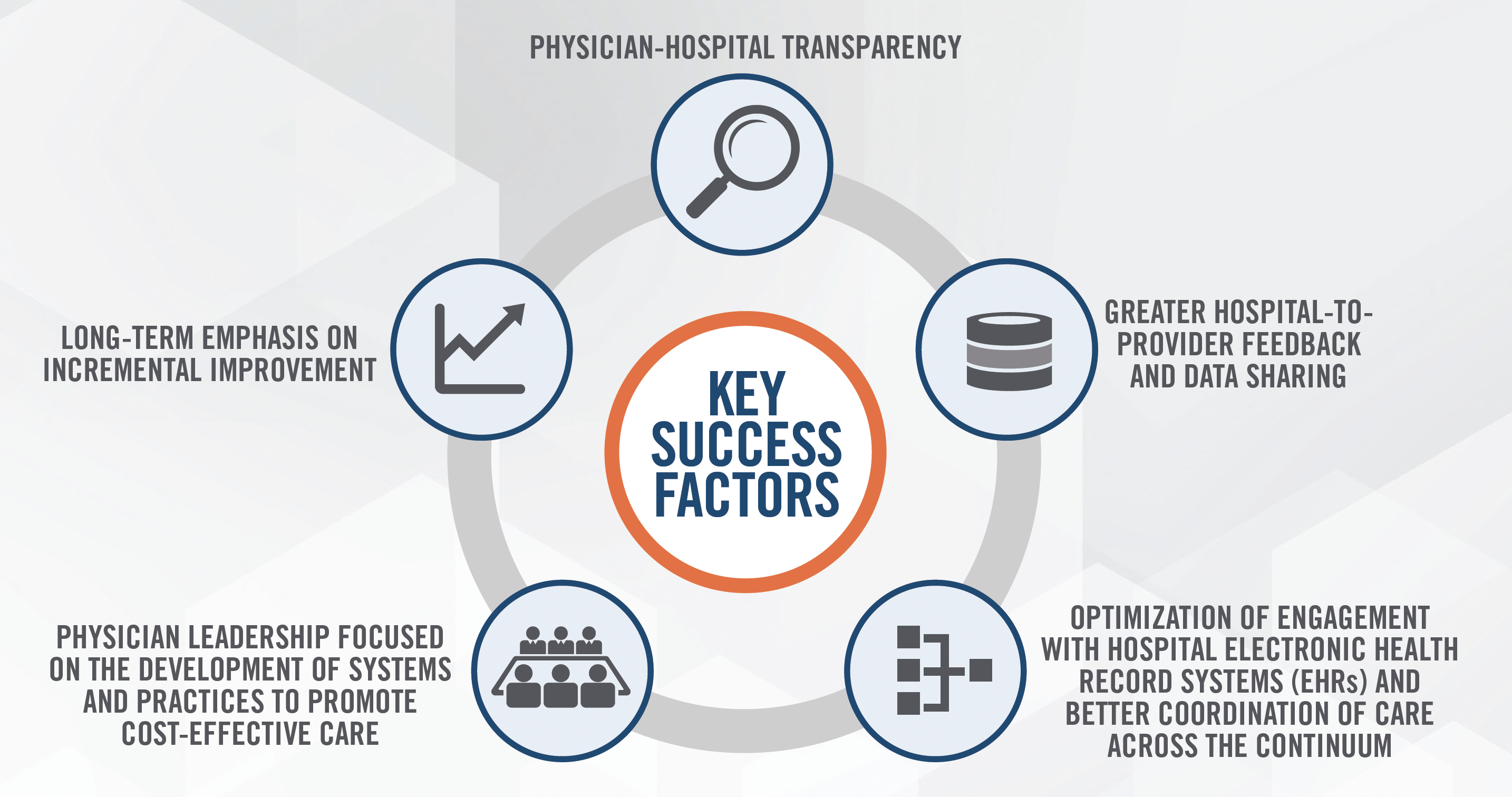

One example is that of high- versus low-performing ACOs. In a 2018 study of participant ACOs in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), the factors of a long-term emphasis on incremental improvement, higher rates of physician-hospital transparency, greater hospital-to-provider feedback and data sharing, strong and well-established physician leadership focused on the development of systems and practices to promote cost-effective care, and optimization of engagement with hospital electronic health record systems (EHRs) were among the most notable factors distinguishing high-performing ACOs, and were more reliably predictive of ACO success than severity of illness.[4] In CMS’s Year 3 Evaluation Report for its Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) Model, hospital interviewee data demonstrated that patient education, better discharge planning, data sharing, collaboration among providers and greater emphasis on data sharing, patient tracking, and follow up were the key care coordination activities common among CJR hospitals that maintained or improved overall patient care and episode cost.[5] Markedly, these activities are all frequent cornerstones of service line co-management, whether by way of the ‘base’ day-to-day duties or via benchmarks and work efforts emphasized through financial incentives.

The quintuple-aim objectives of CMS’s value-based strategy underscore the importance of accountability, quality, patient-centeredness, hospital-provider alignment, and transformative interdisciplinary collaboration as markers of success. Notwithstanding some of the regulatory concerns that have long surrounded service line co-management, well-structured co-management arrangements have been repeatedly tested and proven as an effective strategy to weave these goals into the operational fabric of hospitals and health systems. The establishment of the Value Based Safe Harbors and Exceptions in the 2020 Final Rule may offer additional protections for service line co-management. With nearly two decades of experience providing advisory and valuation services in value-based strategy and the establishment of commercially reasonable care coordination activities and quality metrics, HealthCare Appraisers is the market leader in supporting the development and re-design of successful service line co-management arrangements. Contact us today to learn how we can help position your service line for success.

[1] Defining ‘Referral’ in the Anti-Kickback Statute (americanbar.org)

[2] OIG Advisory Opinion No. 12-22 (hhs.gov)

[3] Revisions to the CMP Law Open the Door for Gainsharing Arrangements with Physicians | News and Publications | Kutak Rock LLP

[4] Factors That Distinguish High-Performing Accountable Care Organizations in the Medicare Shared Savings Program – PMC (nih.gov)

[5] CMS_Comprehensive_Care_for_Joint_Replacement_Model:_Performance_Year_3_Evaluation_Report