Author: Andrea M. Ferrari, JD, MPH

WHAT DO THEY MEAN FOR PHYSICIAN COMPENSATION?

On November 20, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released its long-awaited new Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark Law) Final Rule, culminating its role in the Trump Administration’s Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care. This new Stark Law Final Rule, which was published in the Federal Register December 2, comprises approximately 627 pages and contains noteworthy changes to the “Big Three” Stark Law requirements for physician compensation: (1) commercially reasonable; (2) fair market value; and (3) not taking into account the volume or value of a physician’s referrals or other business generated by the physician (for short, the Volume or Value Standards). Specifically, the Final Rule contains a new definition for the term “commercially reasonable,” a revised definition for the term “fair market value,” and updated guidance regarding what conduct is prohibited by the Volume or Value Standards. It also contains many other significant changes that have the potential to transform the landscape for physician compensation, including, perhaps most notably, new Stark Law exceptions for certain types of value-based physician compensation arrangements. These new exceptions for value-based physician compensation arrangements are to advance the primary goal of the Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care, which was to reduce regulatory barriers and accelerate transformation to a healthcare system that pays for value over volume.

CMS’s release of the new Stark Law Final Rule was coordinated with simultaneous release by the Office of Inspector General (OIG) of new safe harbor regulations for the Federal Antikickback Statute. (AKS) OIG developed its new AKS Final Rule in coordination with CMS to ensure that the new OIG and CMS Final Rules are aligned. However, the new OIG Final Rule differs in some respects from CMS’s Final Rule. For example, OIG’s Final Rule does not contain corresponding new definitions or guidance for the Big Three, and OIG’s new AKS safe harbors for value based arrangements differ somewhat from the new Stark Law exception in the Stark Law Final Rule.

Most provisions of the new Final Rules are effective January 19, 2021. This FMVantage Point is the first in a series that HealthCare Appraisers plans to release between now and then to help our clients understand what the new Final Rules— which together comprise over 1,600 pages— mean for physician compensation. This FMVantage Point provides an overview of the elements of the Stark Law Final Rule that pertain to the Big Three requirements of commercially reasonable, fair market value and meeting the Volume or Value Standards. Future FMVantage Points with explore other aspects of the new Final Rules, including the new exceptions and safe harbors for value based arrangements.

![]() OVERVIEW OF CHANGES TO THE “BIG THREE” IN THE NEW STARK LAW FINAL RULE

OVERVIEW OF CHANGES TO THE “BIG THREE” IN THE NEW STARK LAW FINAL RULE

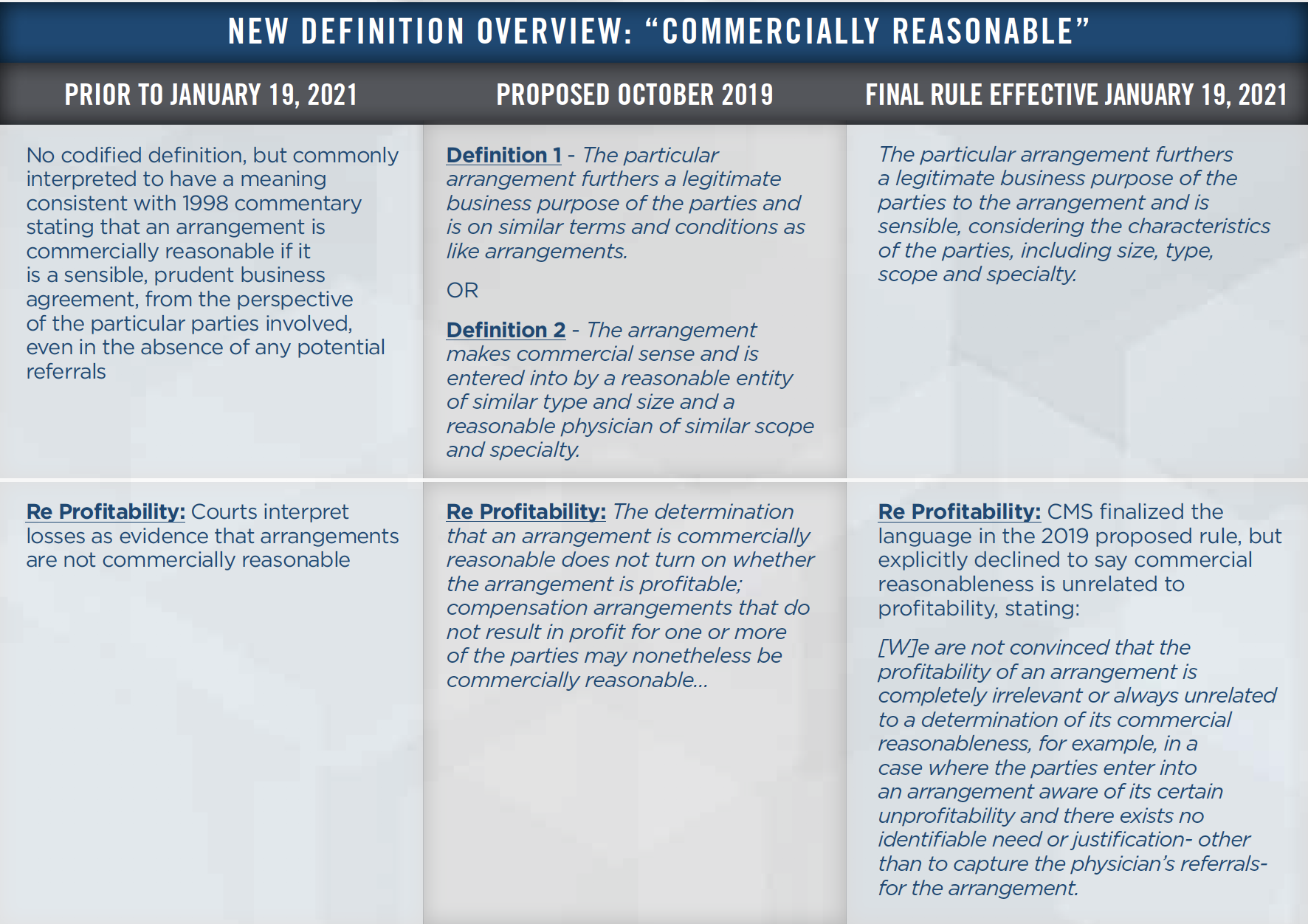

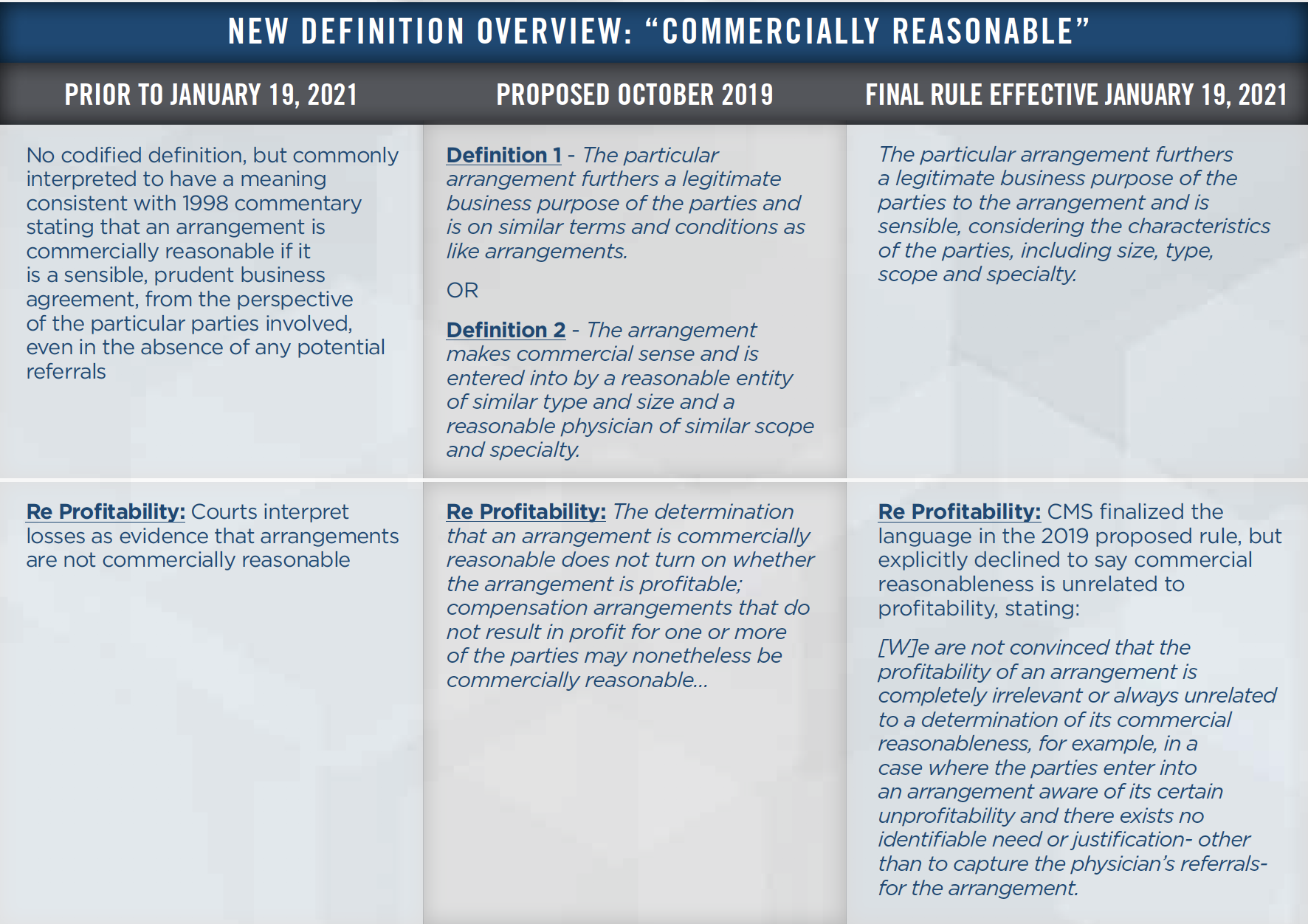

I. New Definition of Commercially Reasonable

Under the new Stark Law Final Rule, “commercially reasonable” means “the particular arrangement furthers a legitimate business purpose of the parties to the arrangement and is sensible, considering the characteristics of the parties, including size, type, scope and specialty.”

Previously, the term “commercially reasonable” was not defined, although it was commonly interpreted in a manner consistent with commentary in a 1998 proposed rule, which stated that an arrangement is commercially reasonable if it “appears to be a sensible, prudent business agreement, from the perspective of the particular parties involved, even in the absence of any potential referrals” (63 FR 1700).

In addition to providing a new definition for commercially reasonable, the new Stark Law Final Rule clarifies that an arrangement may be commercially reasonable even if it does not result in profit for one or more of the parties. The commentary in the Stark Final Rule states:

The determination that an arrangement is commercially reasonable does not turn on whether the arrangement is profitable; compensation arrangements that do not result in profit for one or more of the parties may nonetheless be commercially reasonable… We acknowledge that, even knowing in advance that an arrangement may result in losses to one or more parties, it may be reasonable, if not necessary, to nevertheless enter into the arrangement. Examples of reasons why parties would enter into such transactions include community need, timely access to health care services, fulfillment of licensure or regulatory obligations, including those under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), the provision of charity care, and the improvement of quality and health outcomes.

However, the commentary also indicates that arrangements that are not profitable are in some cases not commercially reasonable, stating:

Although we believe that compensation arrangements that do not result in profit for one or more of the parties may nonetheless be commercially reasonable, we are not convinced that the profitability of an arrangement is completely irrelevant or always unrelated to a determination of its commercial reasonableness, for instance, in a case where the parties enter into an arrangement aware of its certain unprofitability and there exists no identifiable need or justification- other than to capture the physician’s referrals- for the arrangement.

Below are some of CMS’s other comments regarding which arrangements may be “commercially reasonable” (and which might not be) under the new definition.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The introduction of a codified definition for commercially reasonable— one which requires consideration of specific elements of an arrangement and of the parties entering it, including size, type, scope and specialty— may result in nuanced changes in how courts interpret this term and, therefore, in how commercially reasonableness should be evaluated in anticipation of litigation or other challenges to compliance.

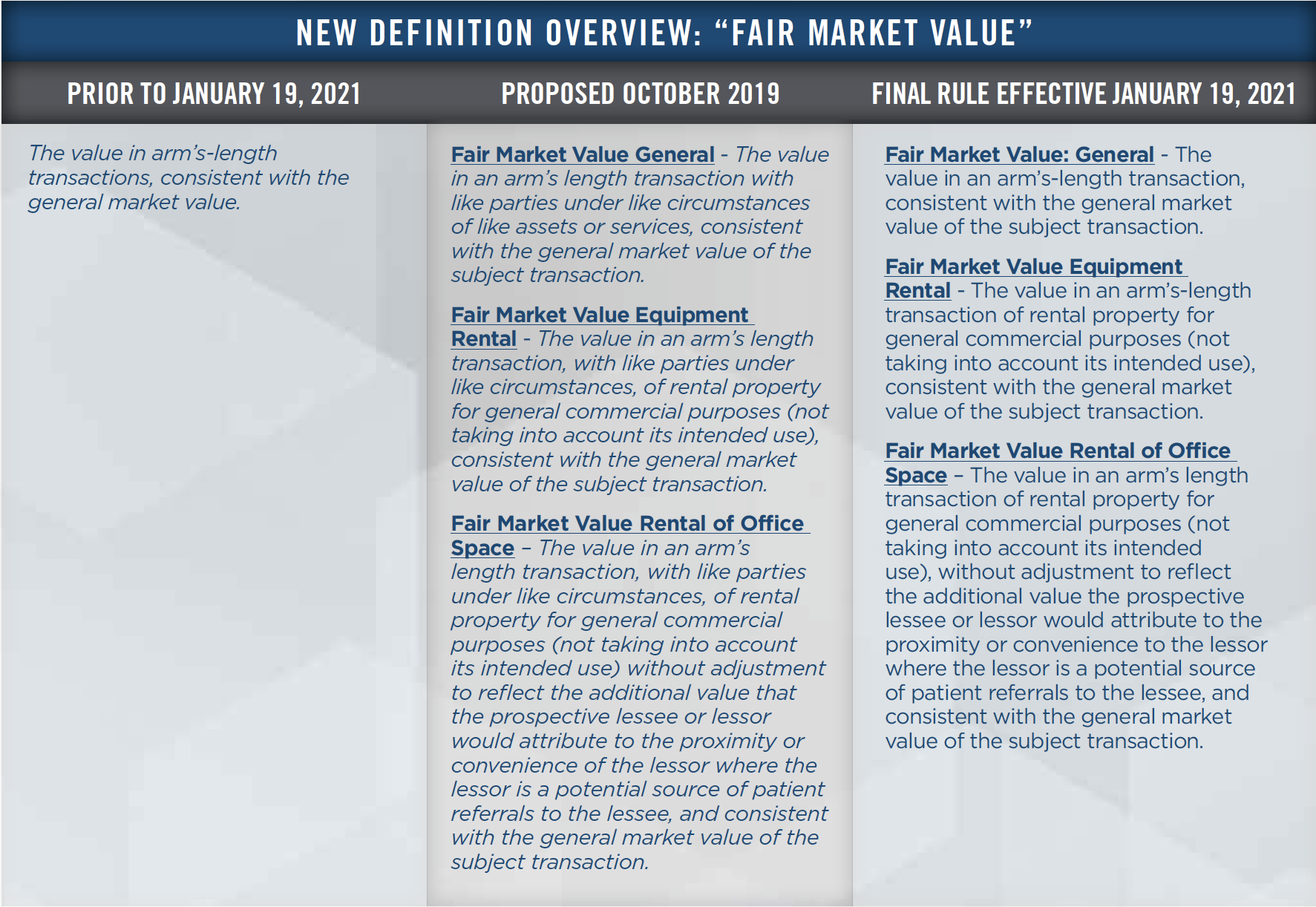

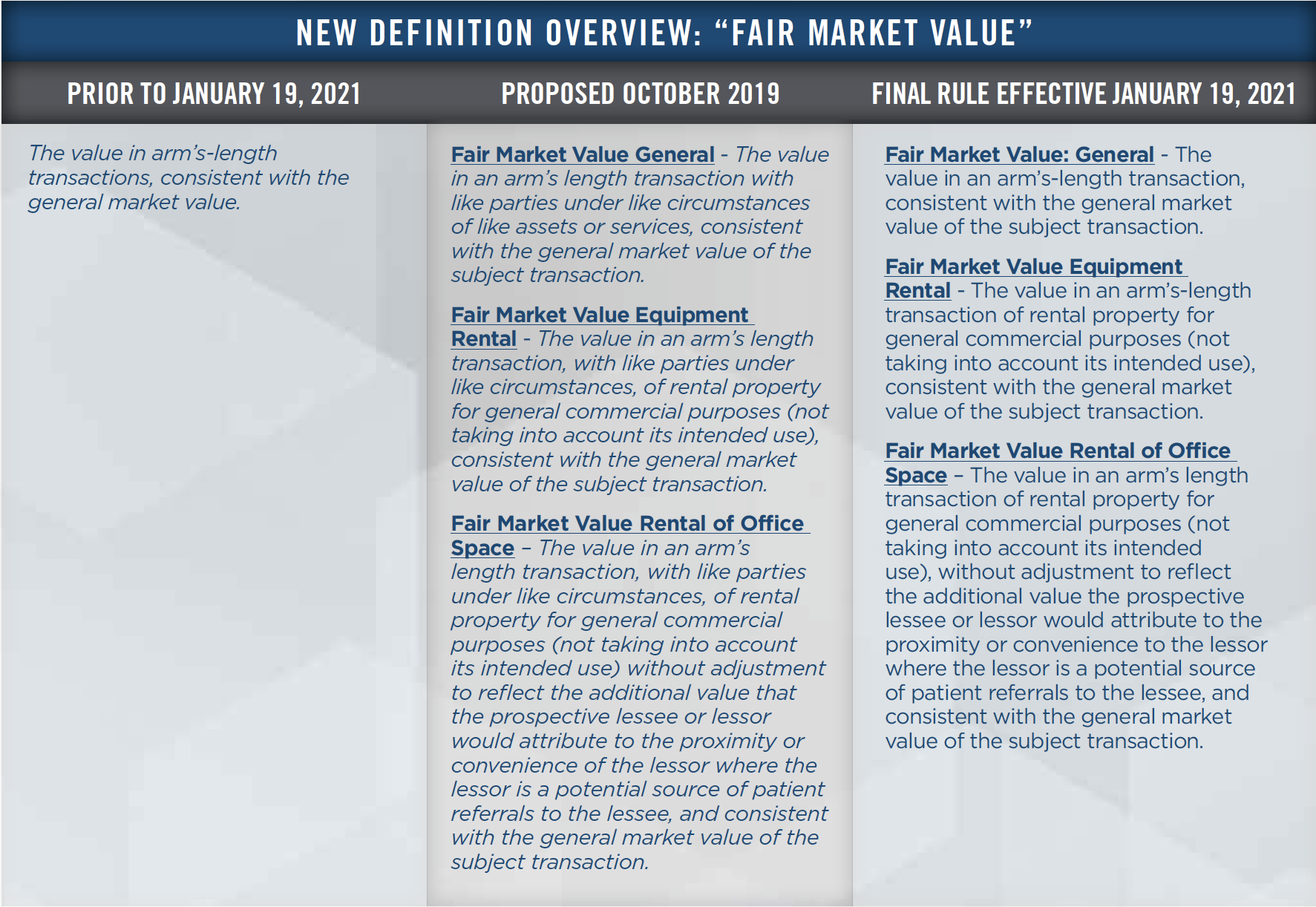

IIA. Revised Definition of Fair Market Value

There are three definitions of fair market value in the Stark Law Final Rule: one definition for general application, another specific to the rental of equipment, and a third specific to the rental of office space.

(1) Under the general application definition: Fair market value means the value in an arm’s-length transaction, consistent with the general market value of the subject transaction.

(2) With respect to rental of equipment: Fair market value means the value in an arm’s-length transaction of rental property for general commercial purposes (not taking into account its intended use), consistent with the general market value of the subject transaction.

(3) With respect to the rental of office space: Fair market value means the value in an arm’s length transaction of rental property for general commercial purposes (not taking into account its intended use), without adjustment to reflect the additional value the prospective lessee or lessor would attribute to the proximity or convenience to the lessor where the lessor is a potential source of patient referrals to the lessee, and consistent with the general market value of the subject transaction.

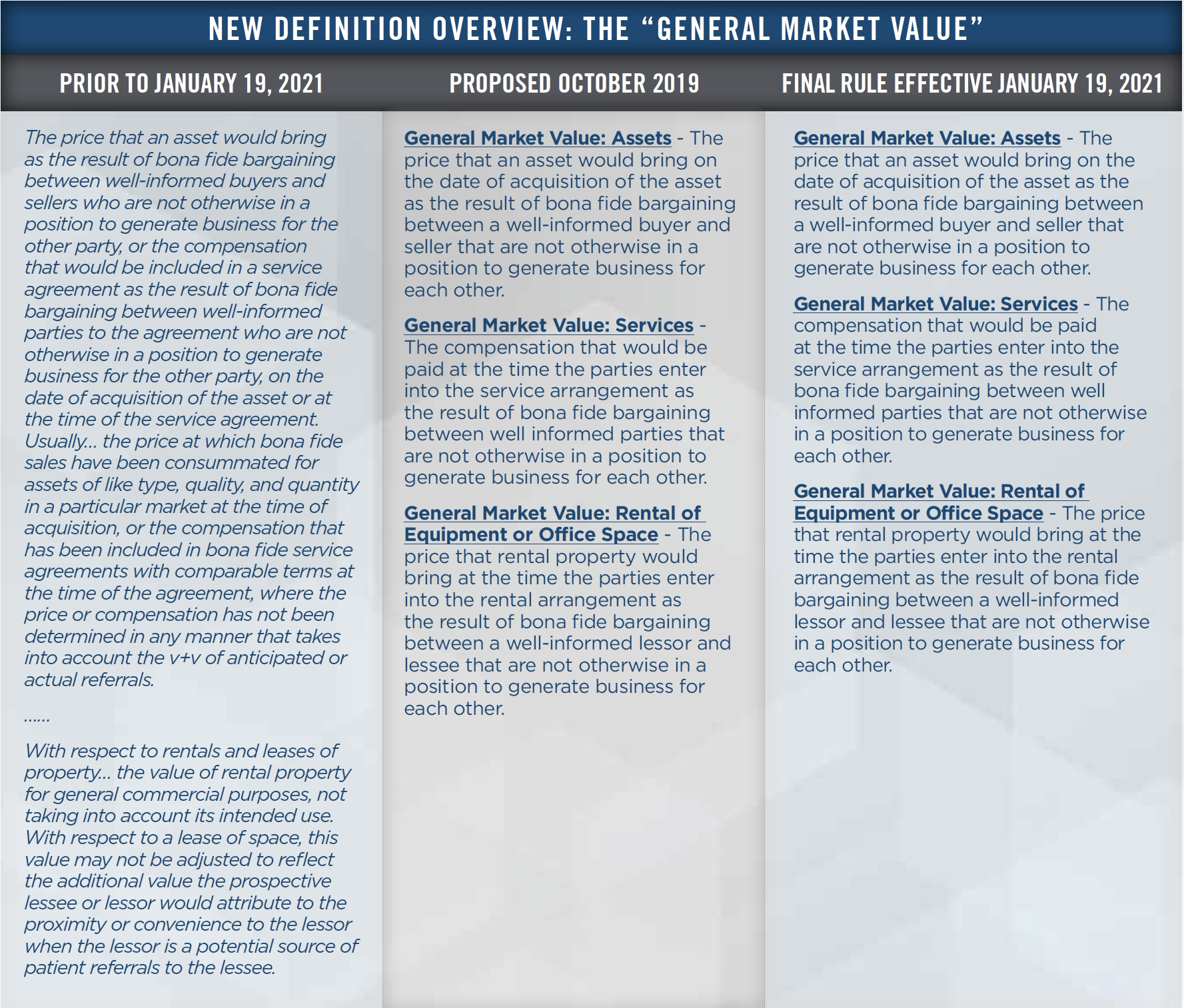

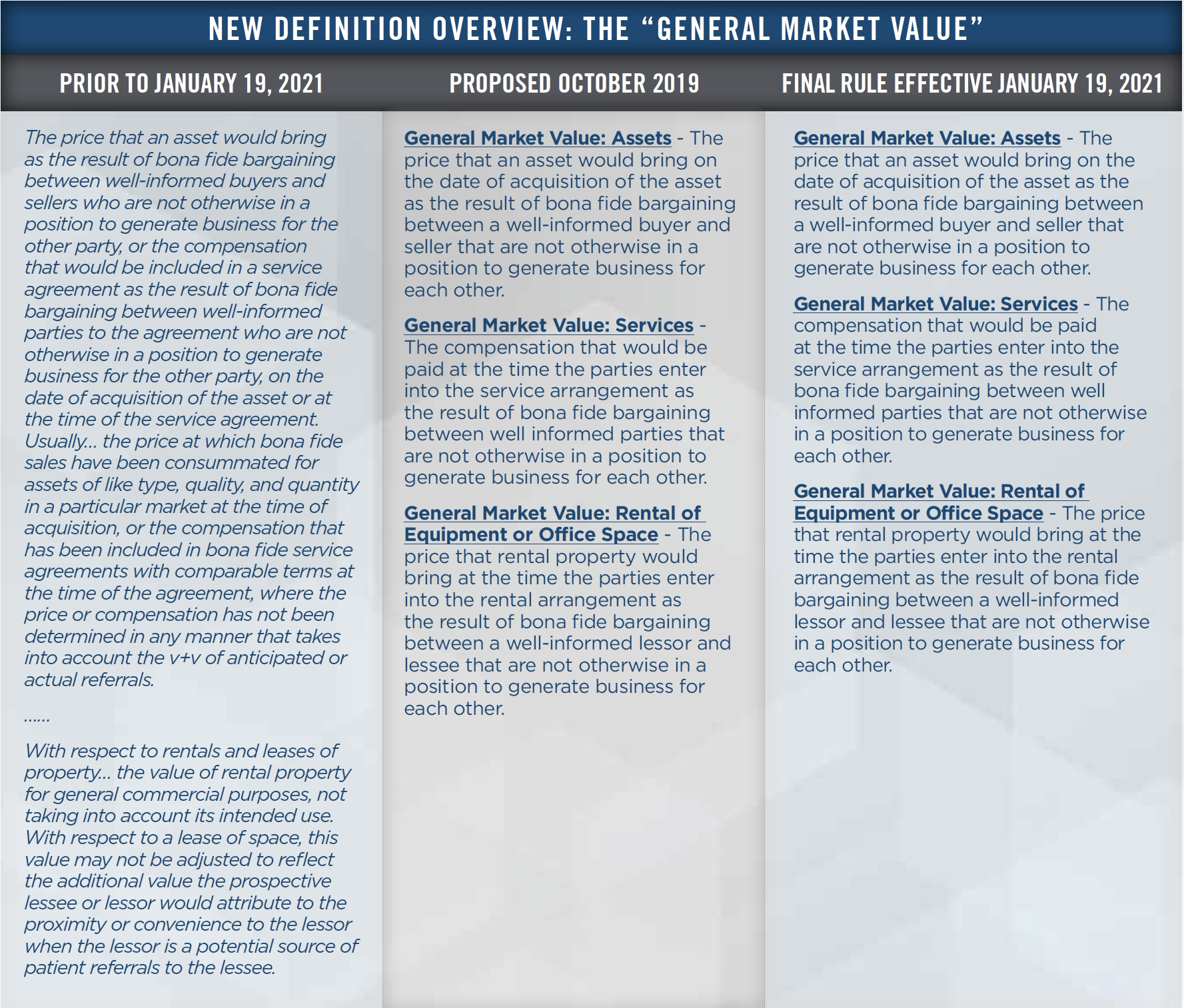

IIB. Revised Definition of the General Market Value

The “general market value” is an element of all three new definitions for fair market value. As defined in the Stark Law Final Rule, the “general market value” means:

(1) With respect to the purchase of an asset, the price that an asset would bring on the date of acquisition of the asset as the result of bona fide bargaining between a well-informed buyer and seller that are not otherwise in a position to generate business for each other.

(2) With respect to compensation for services, the compensation that would be paid at the time the parties enter into the service arrangement as the result of bona fide bargaining between well informed parties that are not otherwise in a position to generate business for each other.

(3) With respect to the rental of equipment or the rental of office space, the price that rental property would bring at the time the parties enter into the rental arrangement as the result of bona fide bargaining between a well-informed lessor and lessee that are not otherwise in a position to generate business for each other.

IIIC. Explanation of Changes from Existing Definitions of Fair Market Value and the General Market Value

The updated definitions of “fair market value” and the “general market value” will replace the definitions that are currently in the Stark Law regulations, which are the following:

Existing definition of fair market value: The value in arm’s-length transactions, consistent with the general market value.

Existing definition of the general market value:

(1) With respect to assets: The price that an asset would bring as the result of bona fide bargaining between well-informed buyers and sellers who are not otherwise in a position to generate business for the other party, on the date of acquisition of the asset.

(2) With respect to services: The compensation that would be included in a service agreement as the result of bona fide bargaining between well-informed parties to the agreement who are not otherwise in a position to generate business for the other party, at the time of the service agreement.[1]

(3) With respect to rentals and leases of property: The value of rental property for general commercial purposes (not taking into account its intended use). With respect to a lease of space, this value may not be adjusted to reflect the additional value the prospective lessee or lessor would attribute to the proximity or convenience to the lessor when the lessor is a potential source of patient referrals to the lessee.

CMS made several comments of note regarding the updated definitions of fair market value and the general market value, some of which are provided below:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Many of these comments are in recognition of the addition of the words “of the subject transaction” after “the general market value” in the definition of fair market value. This addition indicates that general reference to salary survey percentiles may not be indicative of fair market value when survey values don’t reflect the facts and circumstances of the subject transaction. This change may be particularly significant in the current market, which is defined by a variety of unusual and unique circumstances, needs and demands a that have resulted from the COVID public health emergency and new and experimental care delivery and payment models.

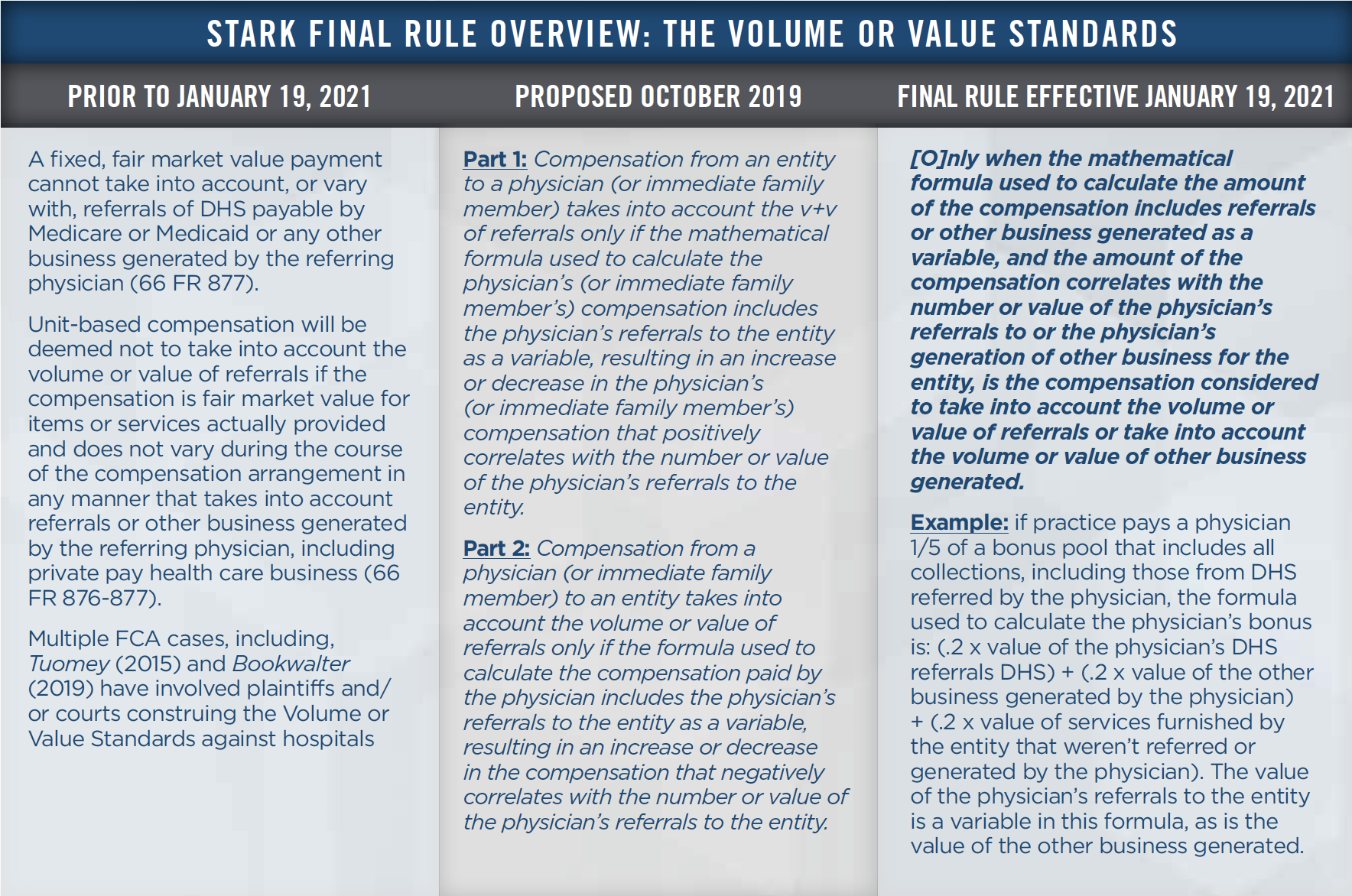

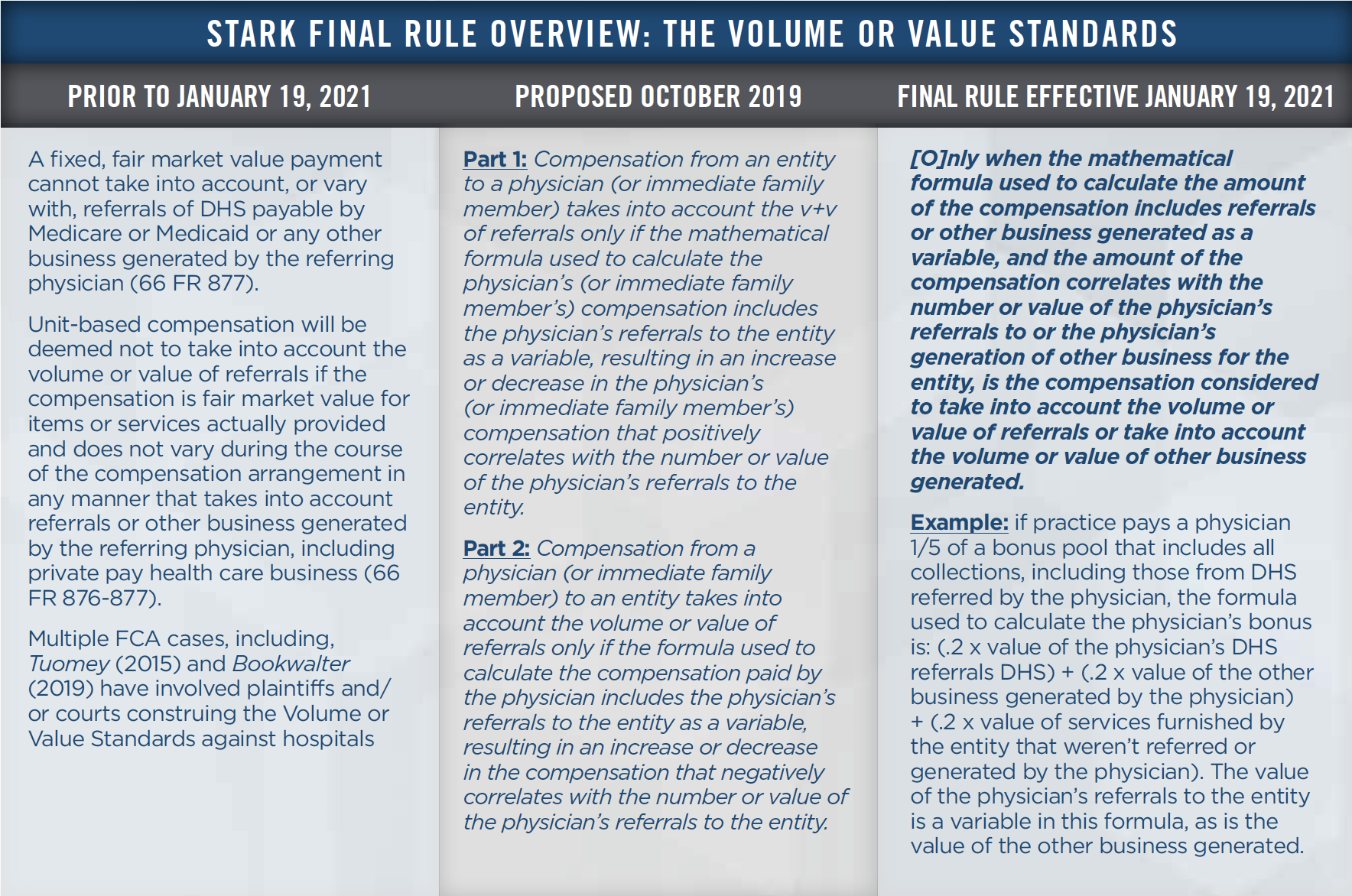

III. The Volume or Value Standard

CMS made clear in the new Stark Law Final Rule that compensation will not fail the Volume and Value Standards unless the mathematical formula used to calculate the amount of compensation includes referrals or other business generated as a variable, and the amount of compensation correlates with the number or value of the physician’s referrals to, or the physician’s generation of other business for, the entity. Importantly, CMS stated that a productivity bonus will not fail the Volume or Value Standards solely because corresponding hospital services (meaning, designated health services) are billed each time the employed physician personally performs a professional service, as may happen with a surgeon. However, CMS also cautioned in the new Stark Law Final Rule that an arrangement under which a hospital makes a payment to a physician in anticipation of future referrals may be suspect under the AKS (even if not the Stark Law), and that a revised definition of “referral” in the Final Rule clarifies that referrals are not items or services to be protected under the exceptions to the Stark Law. As noted below, CMS was clear that the guidance provided in the Stark Law Final rule regarding the Big Three (including regarding the Volume or Value Standards) is specific to compliance with the Stark Law and does not govern compliance with other laws for which these concepts are important, such as the AKS, the Civil Monetary Penalties Law (CMPL) or regulations for tax exempt entities.

Also of significant note in the new Stark Law Final Rule is a clear statement that the fair market value requirement of Stark Law exceptions is separate and distinct from the Volume or Value Standards. In order to satisfy the requirements of the Stark Law exceptions in which these two concepts (fair market value and not taking into account volume or value) both appear, compensation must both: (1) be fair market value for items or services provided; and (2) not take into account the volume or value of referrals (or the volume or value of other business generated by the physician, where such standard appears).

The implications of decoupling fair market value and the Volume or Value Standards will be explored in future publications and in our upcoming roundtable webinars.

IV. What the Stark Law Final Rule Does Not Change About the Big Three

CMS has acknowledged that, although the changes in the new Stark Law Final Rule have significant implications for transactions and compensation between DHS entities and physicians, they do not necessarily redefine how the Big Three will be determined in every case. Specifically, CMS noted that the concepts and guidance in the Stark Law Final Rule relate only to the application of the Stark Law and its regulations and that, although other laws and regulations, including the AKS, may utilize the same or similar terminology, the policies finalized in the Stark Law Final Rule “do not affect or in any way bind OIG’s (or any other governmental agency’s) interpretation or ability to interpret such terms for purposes of laws or regulations other than the [Stark Law].” CMS further specifically noted that:

[The] interpretation of these key terms [in the Stark Law Final Rule] does not relate to and in no way binds the Internal Revenue Service with respect to its rulings and interpretation of the Internal Revenue Code or State agencies with respect to any State law or regulation that may utilize the same or similar terminology. We note further that, to the extent terminology is the same as or similar to terminology used in the Quality Payment Program within the PFS, our final policies do not affect or apply to the Quality Payment Program.

With this in mind, understanding the nuances and extent of legal and regulatory implications of a physician compensation arrangement will continue to be of key importance, as an arrangement that does not, for example, run afoul of the Volume or Value Standards or the definition of commercially reasonable under the new Stark Law Final Rule may still fail to pass muster under the AKS or the rules against private benefit under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code or state law.

![]()

![]()

![]()

For compensation arrangements between physicians and DHS entities, including hospitals and other healthcare businesses, the new Stark Law and AKS Final Rules may have significant implications for the Big Three requirements of commercially reasonable, fair market value and the Volume or Value Standards. Starting January 19, 2021, evaluation of the Big Three will need to be undertaken with consideration for:

1. A new Stark Law regulatory definition for “commercially reasonable”;

2. Three new Stark Law regulatory definitions for “fair market value,” including three new definitions for the incorporated concept of the “general market value”;

3. A new “bright line” test for meeting the Stark Law’s Volume and Value Standards;

4. Decoupling of Big Three for purposes of the Stark Law- meaning commercially reasonable, fair market value and the Volume or Value Standards must be considered independently, and, where each is required for a Stark Law exception, the compensation arrangement must comply with the specific new rule pertaining to each one; and

5. The limited application of the Stark Law definitions to Stark Law requirements, with recognition that other laws and regulations may use the same or similar terminology but require a different approach to the Big Three.

We are hosting a series of roundtable webinars in the near future to address the new Stark Law and AKS Final Rules. You can submit any questions you may have in advance by using the form below. Please be on the lookout for upcoming webinar dates.

[1] With respect to assets and services, the regulatory text states: Usually, the fair market price is the price at which bona fide sales have been consummated for assets of like type, quality, and quantity in a particular market at the time of acquisition, or the compensation that has been included in bona fide service agreements with comparable terms at the time of the agreement, where the price or compensation has not been determined in any manner that takes into account the volume or value of anticipated or actual referrals.