Authors: William B. Eck, Seyfarth Shaw LLP, Washington, D.C.; Andrea M. Ferrari, HealthCare Appraisers Inc., Boca Raton, Florida; Tizgel K.S. High, LifePoint Health, Brentwood, Tennessee; and David S. Szabo, Locke Lord LLP, Boston

On November 4, 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published its “final rule with comment period” implementing the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).1 This highly-anticipated final rule set forth new details, conditions, and timelines for the physician payment changes that will follow from MACRA, which repealed and replaced the unpopular sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula for calculating annual Medicare payment changes for physicians.

MACRA replaced the SGR formula with the Medicare Quality Payment Program or “QPP.” The QPP provides two options for future clinician payments from Medicare: (1) participation in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System or “MIPS”; or (2) participation in one or more Alternative Payment Models or “APMs.”2 Both options will transition clinicians away from traditional “volume based” payment criteria to newer “value based” payment criteria. The likely result is that MACRA will transform the norms for provider compensation throughout the marketplace, given that Medicare payment practices typically set the standard for general market practices.

More often than not, the ability to demonstrate that health care provider compensation is fair market value (FMV) and commercially reasonable is the lynchpin for a regulatory-compliant transaction or arrangement. As recent court cases such as Tuomey3 have illustrated, compensation that does not meet the “FMV” and “commercially reasonable” standards may put providers at risk for financially ruinous consequences. With this in mind, and with recognition that FMV and commercial reasonableness are difficult to appropriately evaluate without an understanding of the market forces that may influence them, this article will discuss how MACRA may transform market forces and economics in the coming years, and how that transformation may affect the questions and answers about FMV and commercial reasonableness of physician compensation.

OVERVIEW OF MIPS

MIPS requires that clinicians participating in Medicare be subject to payment adjustments (positive or negative) based on performance in four categories of measures: (1) quality, (2) advancing care information, (3) clinical practice improvement activities, and (4) cost. Clinicians subject to MIPs include physicians and other care providers such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, and certified registered nurse anesthetists.4 MIPS is designed to incentivize quality and value improvements in health care delivery while maintaining Medicare budget neutrality and thus there will be both “winners” and “losers” under MIPS.5 A certain number of eligible clinicians will be subject to reimbursement reductions in order for others to achieve reimbursement enhancements. Since even those clinicians who are subject to reimbursement reductions may have made investments in new technology or infrastructure in order to have a hope of achieving the reimbursement enhancements, there is some risk inherent in participating in MIPS.

There is a two-year lag between the period during which MIPS performance data is collected (measurement period) and the period during which corresponding payment adjustments are made (payment period).6 A physician who fails to report data or whose reports suggest “below average performance” during a measurement period will suffer the consequences two years later. The final rule relaxed the reporting requirements and performance standards for the 2017 measurement period, but for 2018 and beyond, the standards will be more stringent, which suggests that payment reductions will be looming for more physicians in 2020 and later years.

OVERVIEW OF APMS

Eligible clinicians may avoid participation in MIPS by participating in qualifying APMs. Qualifying APMs must meet specific criteria related to: (1) use of certified electronic health record technology (CEHRT),7 (2) payments conditioned on achievement of quality criteria that are comparable to the quality criteria in the quality performance category of MIPS, and (3) entity risk-bearing for poor performance and monetary losses.8 Providers who participate in qualifying APMs (Advanced APMs) may receive a 5% annual incentive bonus beginning in 2019, with potentially higher incentive payments later.9 However, achievement of these bonuses may require some upfront expenditure – for example, expenditure for new IT, analytics software and/or for enhanced care management processes. One might reasonably speculate that the inevitable need for upfront investment may blunt the net economic benefit of the available incentive payments, at least initially. Moreover, participation in Advanced APMs inherently comes with downside risk: payments must be subject to reduction for failure to achieve benchmark standards, and more than a nominal portion of the risk of loss must be borne by participating clinicians in order for the clinicians to qualify for APM participation as an alternative to MIPS.10

Significantly, a physician could be affiliated with an entity that is set up to be an Advanced APM, but not experience sufficient volume in the alternative payment plan to gain exemption from MIPS. Thus, physicians who seek to participate in Advanced APMs will ignore MIPS performance at their own peril.11

APMS UNDER THE FINAL RULE:

MEDICARE ADVANCED APMS AND OTHER PAYER ADVANCED APMS MUST, IN GENERAL:

- Use electronic health records;

- Pay for professional services based on quality measures similar to MIPS; and

- Require that APM participants, including physicians, bear risk of more than a nominal amount, or be a Medicare or

- Medicaid medical home.

CMS ANNOUNCED ADVANCED APMS SPECIFICALLY INCLUDE:

- Comprehensive Primary Care Plus, a national model under the Affordable Care Act;

- Next generation ACOs;

- Medicare Shared Savings Programs, Tracks 2 and 3;

- Certain Oncology Care Models with two-sided risk; and

- Certain large scale comprehensive ESRD care models.

IMPACT ON PRACTICE COSTS

Initially, physician practice expenses may increase under MACRA due to the need to invest in the infrastructure necessary to achieve the upside benefits of MIPS and APMs. Larger practices may have the most substantial expenditures, but may also have the benefit of being able to spread their costs over a greater number of revenue generators. Smaller practices with more limited purchasing power, including sole providers and small physician-owned groups, may find themselves without access to adequate infrastructure, particularly with respect to IT, and some fear that they may be at a disadvantage in responding to the reimbursement changes. Experts indicate that some of the most expensive but also important investments to prepare for MACRA may be: (1) electronic health records and other tools to permit tracking, aggregation, and analysis of data; and (2) support systems to identify and plan necessary changes in practice patterns. The need for these investments may have substantial impact on the economics of provider service delivery, and consequently, may force changes to the prevailing models of care delivery, as we discuss further below.

IMPACT ON SOURCES AND AMOUNT OF PHYSICIAN COMPENSATION

Medicare is currently a major source of payment for certain types of physician services, including services related to end stage renal disease (nephrology), joint replacement (orthopedics), ophthalmology, and heart disease (cardiology), to name a few. The implementation of MACRA may significantly affect compensation trends for physicians who perform these services. Also, if other payers in the marketplace follow the lead of the Medicare program to model their own payment policies (as often happens), then the effects of MACRA may be quite dramatic and affect providers of nearly all specialties.

The potential for dramatic changes in reimbursement poses some risk for hospitals and health systems that employ physicians. Recent False Claims Act litigation has focused attention on hospital losses as an indicator of inappropriate physician compensation. Some qui tam plaintiffs have successfully argued that such losses are evidence of non-FMV, unreasonable compensation that fails the requirements of the Stark Law, and/or implies violation of the Anti-kickback Statute.12 If current litigation and enforcement trends continue, hospital-affiliated employers may face substantial financial risk if their employed physicians fail to meet the required benchmarks for full reimbursement under MACRA but their employment compensation does not adjust accordingly. Fixed rates of compensation per work relative value unit (wRVU), which were once considered a fairly safe bet for regulatory-compliant physician employment models, have the potential in the future to become fraught with risk.

IMPACT ON PRACTICE MODELS AND CLINICAL INTEGRATION

Physician practice models have evolved and transformed several times in recent decades. In the last five to six years, there has been a wave of provider consolidation, with large numbers of mergers and acquisitions and increasing physician employment by hospitals and health systems and their affiliated organizations. The implementation of MACRA may affect both the pace and direction of the consolidation trend. On the one hand, a desire for economies of scale related to the need for access to IT and other efficiency building infrastructure may increase the interest in consolidation among independent physicians, especially in markets with less favorable payer mix and high dependence on government payers such as Medicare.

On the other hand, the combined effects of increasing practice costs and difficulty projecting future revenue may have a chilling effect for would-be purchasers and managers of many physician practices, particularly in the current enforcement environment, in which the financial impact of transactions with poor economics might easily go from bad to disastrous. Our reference to “disastrous” financial impact is, in part, a reference to the risk of liability under the Stark Law, Anti-kickback Statute, and/or False Claims Act. If the FMV or commercial reasonableness of physician compensation comes into question, as may happen in the wake of a physician practice transaction or physician employment relationship that yields substantial and seemingly unjustified losses for the purchaser and employer, the consequences could be enormous. The difficulty in projecting future revenue arises from both (1) uncertainty about the state of the market given, for example, uncertainty about the potential for repeal and replacement of the Affordable Care Act; and (2) uncertainty about the performance of individual eligible providers under MIPs or their chosen APM. There are also antitrust enforcement concerns about some types of transactions.

The competing desires for economies of scale and mitigation of consolidation risk may increase interest and participation in clinically integrated networks (CINs) and accountable care organizations (ACOs). Participation in a CIN or ACO may allow providers to share and spread the cost of IT, analytics, and care management resources without transferring ownership or accountability for practice performance. However, participation in a CIN or ACO comes with its own set of financial questions, particularly for the hospitals, health systems, and affiliates that already employ physicians and may be the primary owner and funding source for a CIN’s or ACO’s operations. A CIN or ACO can be costly to establish and operate. As such, there is significant financial risk related to poor performance. Does this financial risk become a regulatory compliance risk if losses are not appropriately spread or accounted for in the CIN’s or ACO’s relationships with participating providers and/or in its revenue allocation and distribution plans? Is the risk allocation appropriate to allow the participating providers to qualify as APM participants under the MACRA final rule? Answers to such questions are intertwined with the answers to questions about what constitutes a commercially reasonable and FMV financial arrangement for a provider in the post-MACRA world.

WHAT MACRA MIGHT MEAN FOR FMV AND COMMERCIAL REASONABLENESS DETERMINATIONS

THE IMPORTANCE OF FMV AND COMMERCIALLY REASONABLE COMPENSATION

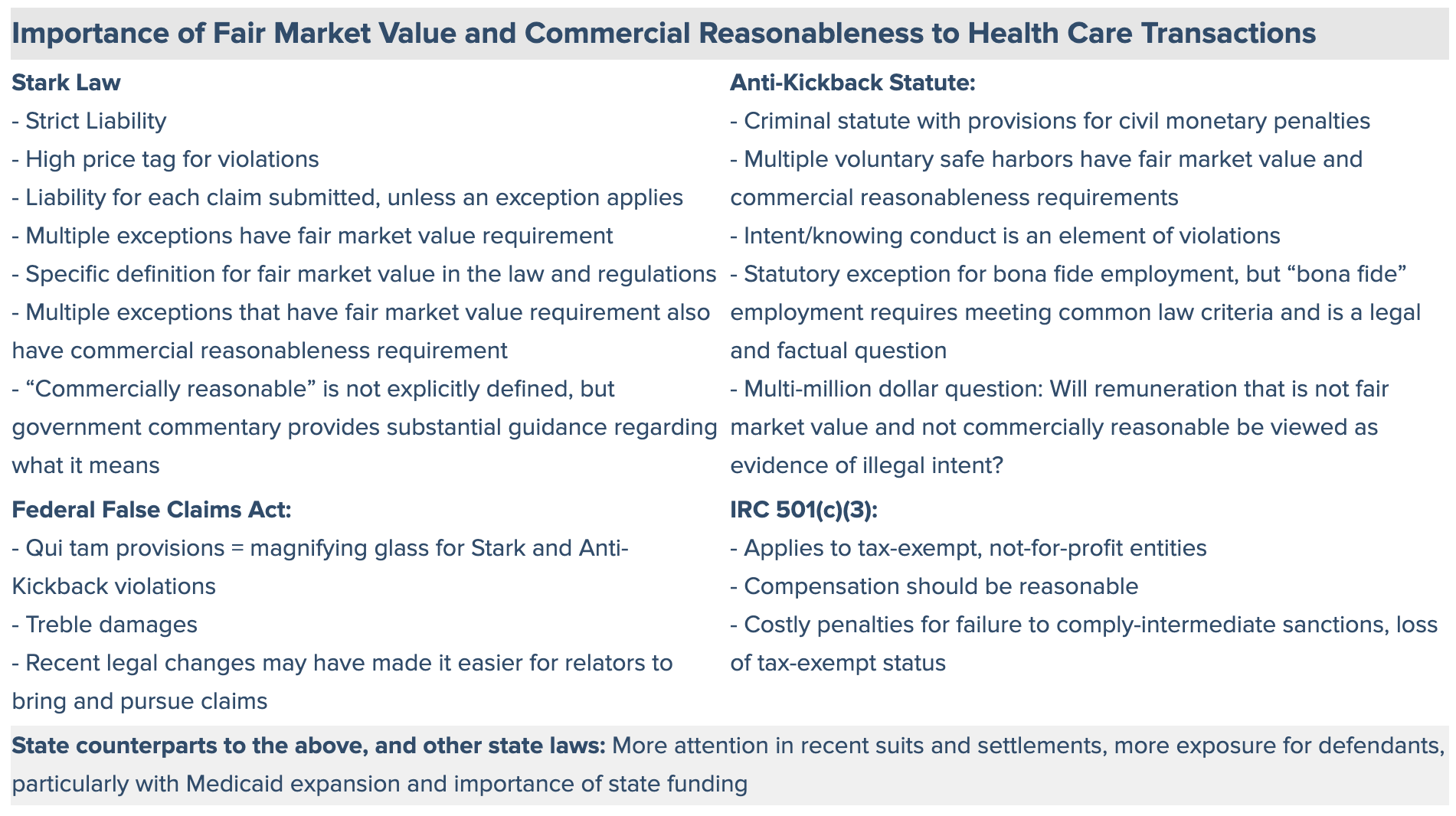

Various laws make “fair market value” and “commercial reasonableness” a legal focus of health care transactions and contracts.13 The law that typically receives the most attention is the federal Physician Self-Referral or Stark Law, a strict liability statute that, absent an exception, is violated when a physician or an immediate family member has a “financial relationship” with an entity (which may be an ownership, investment, or compensation relationship) and the physician makes a “referral” to the entity for the furnishing of any of a specified list of “designated health services” 14 that are payable by Medicare. To avoid liability under the Stark Law, the financial relationship must meet all the requirements for one of an enumerated list of Stark Law exceptions. Many of the exceptions have a requirement that compensation be consistent with or not exceed FMV, and several have a requirement that the compensation arrangement be “commercially reasonable.” Some of the enumerated exceptions do not contain the words “commercially reasonable” but nonetheless contain elements that suggest a need for reasonableness in the financial relationship. For example, the Stark Law exception for personal services arrangements has a requirement that “aggregate services contracted for do not exceed those that are reasonable and necessary for the legitimate business purposes of the arrangement(s).”15

Violations of the Stark Law give rise to liability for each claim submitted pursuant to a prohibited referral. Liability for violations can add up quickly and to astronomical amounts. Repeated or egregious violations may lead to debarment from Medicare and other health care payment programs. Also, the Stark Law is not the only reason to be concerned about whether compensation is FMV and commercially reasonable. There are several other anti-fraud and abuse laws that make FMV and commercially reasonable compensation an implicit imperative, even if not an explicit requirement. The potential liability for violations of these laws may be equally or more troublesome than liability under the Stark Law, particularly if the violations co-exist with violations of the Stark Law.

DEFINITIONS FOR “FAIR MARKET VALUE” AND “COMMERCIALLY REASONABLE”

FMV has a specific definition in the Stark Law. This definition is:

the value in arm’s length transactions, consistent with the general market value, and, with respect to rentals or leases, the value of rental property for general commercial purposes (not taking into account its intended use) and, in the case of a lease of space, not adjusted to reflect the additional value the prospective lessee or lessor would attribute to the proximity or convenience to the lessor where the lessor is a potential source of referrals to the lessee.16

The term “general market value,” which is part of the Stark Law’s definition of FMV, is defined in the Stark Law’s promulgating regulations, as follows:

the price that an asset would bring as the result of bona fide bargaining between well‐informed buyers and sellers who are not otherwise in a position to generate business for the other party, or the compensation that would be included in a service agreement as a result of bona fide bargaining between well‐informed parties to the agreement who are not otherwise in a position to generate business for the other party, on the date of acquisition of the asset or at the time of the service agreement.17

The expanded definition of FMV in the Stark Law regulations sets forth guidance as to how the definition should be applied, stating:

[u]sually, the fair market price is the price at which bona fide sales have been consummated for assets of like type, quality, and quantity in a particular market at the time of acquisition, or the compensation that has been included in bona fide service agreements with comparable terms at the time of the agreement, where the price or compensation has not been determined in any manner that takes into account the volume or value of anticipated or actual referrals. (emphasis added)18

The Stark Law regulations also provide specific guidance for applying the definition of FMV to rentals and leases, stating that in this context, FMV is:

the value of rental property for general commercial purposes (not taking into account its intended use). In the case of a lease of space, this value may not be adjusted to reflect the additional value the prospective lessee or lessor would attribute to the proximity or convenience to the lessor when the lessor is a potential source of patient referrals to the lessee. For purposes of this definition, a rental payment does not take into account intended use if it takes into account costs incurred by the lessor in developing or upgrading the property or maintaining the property or its improvements.19

Although several Stark Law exceptions require that compensation arrangements be commercially reasonable, the Stark Law does not contain a definition for “commercially reasonable.” Nonetheless, various government publications provide guidance regarding tests for a commercially reasonable arrangement.

In 1998, in the introduction to a proposed Stark Law rule, the Health Care Financing Administration (predecessor to CMS) stated, “We are interpreting commercially reasonable to mean that an arrangement appears to be a sensible, prudent business agreement, from the perspective of the particular parties involved, even in the absence of any potential referrals.”20 In 2004, in the Preamble to the Stark Law Interim Phase II final rule, CMS stated, “An arrangement will be considered ‘‘commercially reasonable’’ in the absence of referrals if the arrangement would make commercial sense if entered into by a reasonable entity of similar type and size and a reasonable physician (or family member or group practice) of similar scope and specialty, even if there were no potential DHS referrals.”21

With limited authoritative guidance on what “commercially reasonable” means, these statements from the agency charged with enforcing and issuing guidance for the Stark Law may represent the best guideposts for determining compliance with the Stark Law exceptions requiring a commercially reasonable arrangement. The statements suggest that the term commercially reasonable describes a financial arrangement that would make business sense even if there were no possibility for referrals between the parties entering into it. Clearly, referrals cannot play any role in the justification of a financial transaction between a DHS entity and a referring physician.

THE IMPACT OF MACRA

Based on these definitions for FMV and commercially reasonable, MACRA-driven changes to health care delivery and economics may significantly affect whether and which arrangements meet the FMV and commercially reasonable standards. As payer rules change, market forces also change, and such changes are likely to affect how much and under what circumstances parties may be willing to compensate each other for items or services. As a result, long standing assumptions about which arrangements make commercial sense and which don’t, and about what compensation is fair market value and what is not, may need to be reconsidered.

With changing payment rules, new trouble spots may include: multi-year agreements with non-adjusting salary guarantees or fixed compensation per hour or per wRVU; bonuses or penalties that are inconsistent or incompatible with known payer quality initiatives; and financial metrics that suggest inappropriate risk (or lack of risk) for one party versus another. Depending on the details, such arrangements may put one party in a position to experience substantial and uncontrolled losses due to poor performance of the other party or adverse changes in reimbursement rules; and in some cases may be inconsistent with reasonable or prevailing business practices.

Some types of previously uncommon compensation arrangements have become and may in the future become more prevalent after MACRA, including arrangements based on gainsharing or “pay for performance” principles. Determining whether these newer arrangements provide for compensation that is FMV and commercially reasonable requires an understanding of the influence and effect of new market forces, and how available data may be affected by those forces. The most commonly-utilized sources of provider compensation data are annually published surveys. The survey data, although highly useful, provide a retrospective rather than current snapshot of market practices, and, in an evolving marketplace with changing rules and rapidly shifting payment trends, the data from such surveys may need to be considered carefully, with understanding for context. Compensation that was negotiated in 2014, was paid in 2015, and is reported in 2016 or 2017 publications may reflect the economics of the pre-MACRA world. To the extent that MACRA will change how much and under what conditions providers will be paid, currently-available survey data might not be the best basis to determine reasonable or FMV compensation for the post-MACRA era. Just as a driver cannot navigate by looking only in the rear view mirror, health care organizations may no longer be able to rely solely on retrospective compensation analyses for fair market value and commercial reasonableness.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR COMPLIANT PHYSICIAN TRANSACTIONS DURING THE MACRA TRANSITION

Many of the newest and most challenging compensation questions will need to be answered with consideration for not only how and how much parties have been paid in the past, but also how and how much similarly situated parties might be paid as health care rules and economics change. To some degree, the latter may be reasonably surmised based on survey data trends and current observations of market behavior. However, even the most reasonable supposition may turn out to be wrong. This being the case, ensuring regulatory compliance may demand periodic and frequent reevaluation of compensation- perhaps once per year- until the MACRA payment transition is complete.

Focus areas for periodic reevaluation may include but not be limited to:

- Modification to salary guarantees;

- Modification to compensation rates or compensation caps;

- Modification to minimum performance standards;

- Downside risk for poor performance or revenue reductions;

- Allocation of increased practice expenses for IT and care management costs; and

- Shifting market trends and value indications, particularly those related to quality of care.

Compensation terms for periodic reevaluation during the MACRA payment transition:

- Salary guarantees

- Compensation rates (per hour, per wRVU, etc.)

- Bonuses and penalties for quality achievements

- Incentive payments based on measures other than quality

- Aggregate annual compensation caps

Potential areas for attention as part of reevaluation:

- Modifications to salary guarantees

- Modifications to compensation rates

- Allocation of risk for poor performance on key indicators and associated revenue losses

- Allocation of new expenses and/or compensation related to use of IT, care management processes

- Allocation and “stacking: of value-based payments and incentives, including ACO/CIN distributions, gainsharing and shared savings payments, and other revenue that is not directly tied to traditional measures of productivity

CONCLUSION

Post-MACRA payment rules have the potential to transform the nature and economics of arrangements and transactions among providers. There are uncertainties regarding the timeline for that transformation and what the market will look like afterward, but it is clear that providers should be prepared for changes and should plan transactions and contracts accordingly. Preparing may include being aware of and considering the potential impact of shifting market forces on how and how much providers are being paid, and implementing stoplights in contracting and payment processes to prompt appropriate pauses and reconsiderations when needed to ensure that compensation is and continues to be consistent with the key standards of FMV and commercial reasonableness.

1 Medicare Access and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), P.L. No. 114-10 (Apr. 16, 2015). The final rule was posted to the CMS website on October 14, 2016 and was published in the Federal Register on November 4, 2016. See 81 Fed. Reg. 77008 (Nov. 4, 2016).

2 Id. at 77009.

3 See U.S. ex rel. Drakeford v. Tuomey Health System, Inc., No. 3:05-2858- MBS (D.S.C.), which was a qui tam relator’s lawsuit brought under the federal False Claims Act. After nearly a decade of litigation, including two jury trials, Tuomey Health System was ordered to pay $237.5 million for violations of the Stark Law and federal False Claims Act. The verdict was upheld on appeal to the Fourth Circuit, and then settled for $72.4 million. At issue in Tuomey was the compensation paid in part-time physician employment arrangements that the government and relator (with an opinion of their expert) contended was not fair market value, not commercially reasonable, and took into account the volume and value of referrals from the physicians.

4 81 Fed. Reg. at 77039; see also, www.qualitypaymentprogram.CMS.gov.

5 81 Fed. Reg. at 77016 (“The final score will be used to determine whether a MIPS eligible clinician receives an upward MIPS payment adjustment, no MIPS payment adjustment, or a downward MIPS payment adjustment as appropriate. Upward MIPS payment adjustments may be scaled for budget neutrality, as required by MACRA.”).

6 Id. at 77083; www.qualitypaymentprogram.CMS.gov.

7 Id. at 77019, 77408-9.

8 Id. at77406, 77408.

9 Id. at 77480.

10 Id. at 77422-3.

11 See CMS, The Quality Payment Program, https://www.cms.gov/ Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-10-25.html (viewed Dec. 27, 2016).

12 See, e.g., U.S. ex rel. Drakeford v. Tuomey Health System, supra note 3.

13 The federal Physician Self-Referral (Stark) Law (42 U.S.C. § 1395nn), the federal Anti-Kickback Statute (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7(b)) and federal False Claims Act (31 U.S.C. § 3729) are generally regarded as the primary reasons for giving careful attention to the fair market value and commercial reasonableness of compensation paid in health care transactions. In addition to these potentially applicable laws, for entities that are not-for-profit and tax-exempt under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, there is a need to avoid engaging in transactions that produce private inurement or excess private benefit, which is generally accomplished by ensuring that compensation paid in transactions is “reasonable.” In a state in which local laws and regulations include counterparts to any the above-referenced federal law and regulations, state laws and regulations may be an additional reason to give consideration to compensation terms – including FMV and reasonableness.

14 DHS is defined in the Stark Law to include: (i) clinical laboratory services; (ii) physical therapy services; (iii) occupational therapy services; (iv) radiology services, including magnetic resonance imaging, computerized axial tomography scans and ultrasound services; (v) radiation therapy and supplies; (vi) durable medical equipment and supplies; (vii) parenteral and enteral nutrients, equipment and supplies; (viii) prosthetics, orthotics and prosthetic devices and supplies; (ix) home health services; (x) outpatient prescription drugs; (xi) inpatient and outpatient hospital services; and (xii) outpatient speech and language pathology services.

15 42 C.F.R. § 411.357(d).

16 42 U.S.C. § 1395nn(h)(3).

17 42 C.F.R. § 411.351.

18 Id.

19 Id.

20 63 Fed. Reg. 1659, 1700 (Jan. 9, 1998).

21 69 Fed. Reg. at 16093 (Mar. 24, 2004).