Authors: Andrea M. Ferrari, JD, MPH and Adria Warren, JD, partner, Foley & Lardner, LLP

Originally Published by Becker’s Hospital Review | May 2016

I. INTRODUCTION

For healthcare providers, and in particular for hospitals and physicians, 2015 was an interesting year that was full of surprising twists and zigzagging transactional trends. In the first half of the year, new legislation in the form of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (“MACRA”) promised radical transformation in the way physician services are reimbursed, and also some significant changes for hospitals, including what seems like encouragement for previously-proscribed gainsharing arrangements.

Later in the year, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 brought unexpected change to the rules governing Medicare payment for off-campus outpatient hospital services, with potentially significant implications for pending transactions and future hospital expansion. In between, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) issued several potential “game changing” regulatory releases, including new proposed (and then finalized) changes to the Stark law regulations, significant additional new guidance on activities related to gainsharing, and also newly proposed guidance regarding participation in the 340B drug pricing program.

As 2016 progresses, physicians and hospitals face a number of significant changes. Many of the changes are a result of the aforementioned developments of 2015. Some relate to the ongoing post-Affordable Care Act evolution of “value-based payments” for health care services. Others relate to changes in the regulatory enforcement environment. This whitepaper provides an overview of the changes facing hospitals and their physician medical staffs, and provides some tips for hospitals seeking to navigate the new landscape, particularly as they consider clinical integration with other providers and other aligning ventures.

REGULATORY LANDMARKS OF 2015

- DHH announces a goal of tying a substantial portion of Medicare payments to measures of quality and value in the next two to three years.

- MACRA/SGR legislation heralds a transformation in the ways providers are paid, and signals changes in the government’s enforcement priorities.

- The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (“BPCI”) project expands, with participation in the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model (“CJR”) to become mandatory for certain providers in 2016.

- The 2016 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule brings the first significant changes to the Stark Law regulations in several years. The changes include new Stark Law exceptions for physician timeshare arrangements and for hospital payments to a physician to recruit a non-physician provider.

- The Department of Justice (“DOJ”) releases the “Yates Memo,” indicating that, as matter of policy, it will seek to identify individual accountability and culpability when investigating claims of corporate violations.

- The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, signed into law on November 2, 2015, contains provisions that will exclude any off-campus hospital outpatient department (“HOPD”) formed after that date from reimbursement under Medicare’s outpatient hospital prospective payment system (“OPPS”) starting after December 31, 2016.

- The 2016 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule brings the first significant changes to the Stark Law regulations in several years. The changes include new Stark Law exceptions for physician timeshare arrangements and for hospital payments to a physician to recruit a non-physician provider.

- The Department of Justice (“DOJ”) releases the “Yates Memo,” indicating that, as matter of policy, it will seek to identify individual accountability and culpability when investigating claims of corporate violations.

- The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, signed into law on November 2, 2015, contains provisions that will exclude any off-campus hospital outpatient department (“HOPD”) formed after that date from reimbursement under Medicare’s outpatient hospital prospective payment system (“OPPS”) starting after December 31, 2016.

SELECTED SAMPLE OF 2015 GOVERNMENT SETTLEMENTS INVOLVING CLAIMS OF TRANSACTIONS THAT WERE NOT FAIR MARKET VALUE, NOT COMMERCIALLY REASONABLE AND/OR TOOK INTO ACCOUNT VOLUME OR VALUE OF REFERRALS

- Citizens Medical Center (Texas) – $21.8 million settlement; included claims made against hospital administrators

- Mercy Health Springfield Communities (Missouri) – $5 million settlement with health system

- Columbus Regional Health (Georgia) – Up to $35 million to be paid by health system (depending on contingencies), and an additional $425,000 to be paid personally by a physician defendant

- North Broward Hospital District (Florida) – $69.5 million settlement with health system

- Adventist Health System (Florida and Georgia) – $118 million settlement with health system, $115 million to go to the Federal government and the remainder to state governments

- Tuomey Healthcare System (South Carolina) – $72.4 million settlement with health system after an appeals court upheld a $237 million government verdict against the health system

- Memorial Health System of Savannah (Georgia) – $9.8 million settlement with health system

II. TRANSACTION TRENDS OF 2015

We’ve identified three broad categories of hospital transaction trends from 2015: (1) consolidation, (2) clinical integration and alignment, and (3) adoption of transformational compensation models. Each is discussed below.

1. CONSOLIDATION

2014 was defined by its high volume of hospital mergers and physician practice acquisitions. Arguably, the major trend of 2014 was consolidation. During 2015, the consolidation trend continued with gusto. However, a key takeaway from 2015 was that many consolidation transactions, including acquisitions, are becoming more complex, with more potential implications to consider. These transactions may implicate antitrust laws, fraud and abuse laws, state corporate practice of medicine restrictions, and a variety of other laws and regulations applicable to health care providers. Such transactions are also subject to a variety of new business considerations based on changes in the marketplace and the regulatory landscape. Regardless, they remain popular and important avenues for expanding services and achieving coordination and efficiencies in care delivery. The table below illustrates some of the threshold business considerations in embarking on a consolidation transaction.

KEY ISSUES IN CONSOLIDATION TRANSACTIONS AND POTENTIAL DEAL BREAKERS:

- Due diligence

- Electronic health records/IT platform and interfaces

- Operational integration

- Timing and respecting existing arrangements (i.e., space leases)

- Governance/decision making

- Restrictive covenants, exclusivity and right of first refusal

- Duration/Unwind

- Changing economics/payor policies

2. CLINICAL INTEGRATION AND ALIGNMENT

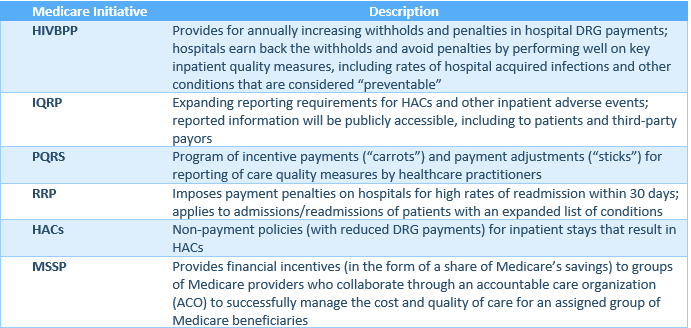

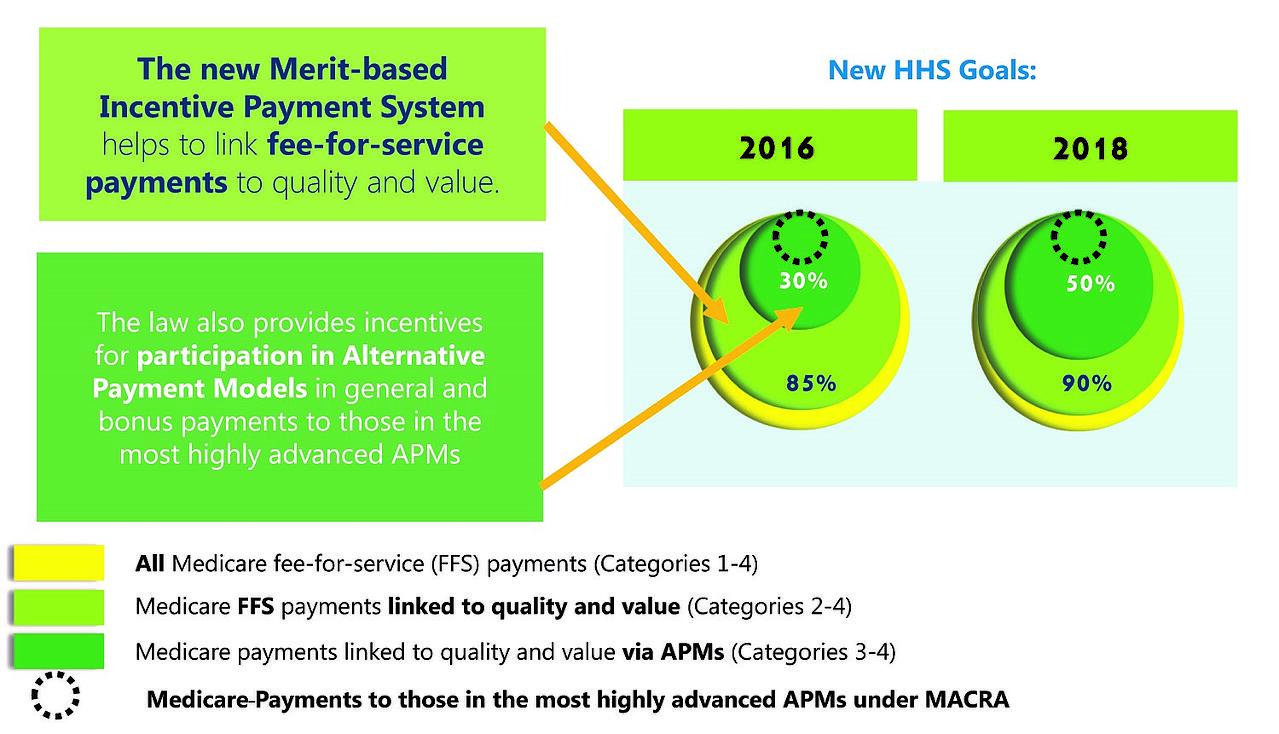

Most indications are that the Medicare program will continue to implement payment rule changes to incentivize quality and cost-effectiveness in healthcare services. In January 2015, HHS announced its goal of tying 30% of traditional, fee-for-service Medicare payments to quality or value through alternative payment models, such as Accountable Care Organizations (“ACOs”) or bundled payment arrangements, by the end of 2016, and tying 50% of payments to these models by the end of 2018. HHS also announced a goal of tying 85% of all Medicare payments to quality or value by the end of 2016, and 90% by 2018, through programs such as the Readmissions Reduction Program and Hospital Inpatient Value Based Purchasing Program. An HHS press release of January 2016[3] indicates that HHS continues to pursue these goals and believes that it is on track to achieve them.

With passage of MACRA in 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) was directed to develop and implement a Merit-Based Payment System (“MIPS”) and alternative payment models (“APMs”) for physicians, and to accelerate or at least maintain the “path to value” in Medicare payment rules for hospitals. Since history suggests that private payors and state Medicaid programs follow the lead of the Medicare program with respect to payment policies and programs, these developments in the Medicare program suggest that quality and “value” are likely to become increasingly important focal points as healthcare evolves from this point.

MEDICARE’S VALUE INITIATIVES

THE WORLD AFTER MAACRA (GRAPHIC BY CMS)

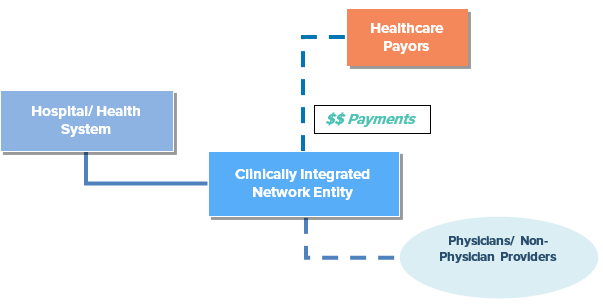

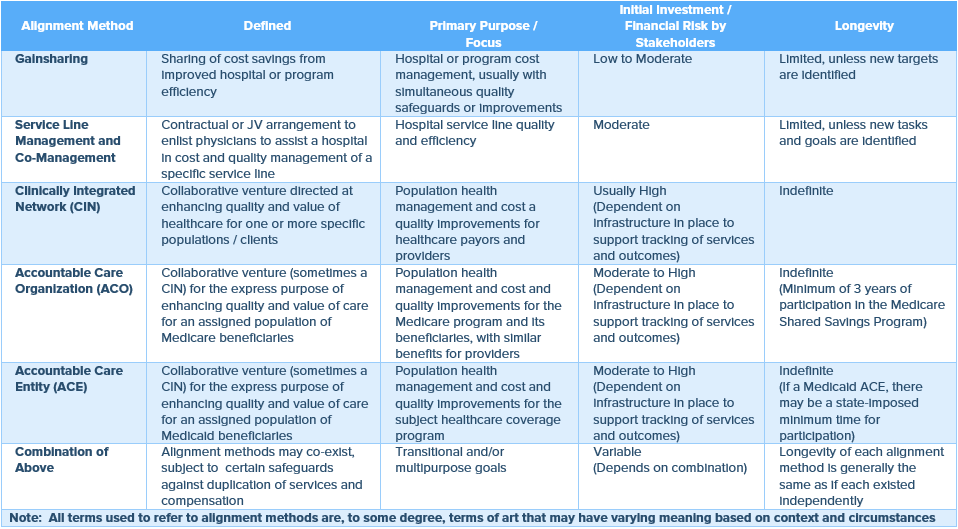

In 2015, there seemed to be growing interest and activity focused on joint ventures, affiliations, partnerships, and formation of clinically integrated networks (“CINs”) and other collaborative ventures that bring hospitals and other providers together in a legally-compliant way to pursue common objectives, but allow them to retain certain financial and operational independence. CINs, in particular, are being explored a number of hospitals as a means to foster coordination of care among independent providers and, thereby, help ensure healthier patients and better outcomes in hospital care.

Unlike other aligning ventures, such as the traditional service-line co-management arrangement, which generally involves a select group of physicians managing a single healthcare service line, a CIN may align providers across the spectrum of care, including the front-line primary care providers whose management of patient care processes can be instrumental in achieving the triple aim of improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of health care.

Participation in a successful CIN may foster substantial improvement in a hospital’s achievement on measures of quality and value, either indirectly by contributing to a healthier patient population that has lower rates of hospital-acquired conditions and readmissions, or directly through the CIN’s contributions to a formal “Hospital Quality and Efficiency Program” or other program that directly incentivizes independent providers to work to improve quality and efficiency in hospital care.

ALIGNING METHODS

Still, establishing and/or participating in a CIN may require substantial financial outlay, including for the information technology and other infrastructure that are essential for performance tracking, and for legal and other professional advice to help navigate antitrust considerations, tax exemption implications, privacy and security regulations, and other applicable laws and regulations. Various Federal and state laws may be implicated by the development and operation of the CIN and the distribution of incentive payments through the network. In short, there are myriad issues that make the establishment of and/or participation in a CIN a complex undertaking. However, the long-term benefits of being part of a successful network may be quite substantial, particularly if healthcare continues to evolve as expected and the market’s competitive forces change as expected.

The various factors that are encouraging hospitals to focus on quality and value are not only increasing interest in broad initiatives such as CINs, but also increasing interest in more service-specific provider alignments, such as service-line co-management arrangements, departmental gainsharing, and various types of provider partnership and affiliation agreements.

In 2015, several new trends emerged in the long-popular concept of co-management. Among them was a shift toward quality-focused incentives in these arrangements, and inclusion or layering of gainsharing with the “traditional” co-management structure, particularly after MACRA modified the prohibition on paying physicians for reducing services.

There also seemed to be an increase in the volume of “alternative” collaborative ventures. Some of these alternative ventures were co-branding or integrated care arrangements with specialized service providers, such as providers of home care or palliative care. Others were affiliation agreements, such as between small community hospitals and larger academic research centers that could offer access to cutting edge research and best-in-their-field physicians. Generally, these types of arrangements, appropriately implemented, may allow hospitals to cost effectively increase the scope and quality of their services by partnering with other service providers and efficiently positioning themselves for the new, value-based reimbursement landscape.

As 2016 unfolds, it seems that hospitals are continuing to carefully consider how their operations and arrangements can put or keep them on the “path to value.” Although none of us has a crystal ball, it seems likely that the trends of 2015 will continue, and that there will be more collaboration and creativity in service offerings in attempts to provide better care at lower cost. This may mean new and different streams of compensation for providers, particularly if “pay-for-performance” models continue to become more pervasive and “incentive” payments replace or are layered with traditional forms of services compensation… which brings us to the third trend of 2015.

4. CHANGES IN EXISTING COMPENSATION PLANS TO INCENTIVIZE VALUE

Increased emphasis on measures of quality and value by healthcare payors has been affecting even commonplace and longstanding hospital agreements, including employment agreements, medical director agreements, and exclusive and non-exclusive professional services agreements. Hospitals are increasingly incorporating quality and value incentives into their service agreements, sometimes putting a certain amount of compensation at risk based on achievement of specific quality and value targets.

Throughout the marketplace, the structuring and criteria for incentive compensation varies based on a variety of factors. This is perhaps expected, given the varying cultures, economics and business practices of organizations. However, the dynamic nature of the regulatory environment, coupled with the recent intensity of regulatory scrutiny (and magnitude of financial exposure for subjects of that scrutiny), suggests that innovative, unique or unusual compensation arrangements should be approached and reviewed carefully.

“Innovative” performance measures or overlapping incentive arrangements may be reasonable and desirable for a variety of reasons, and in an appropriate context and compensation model, they may be important to advancing achievement of the goals that government regulation exists to promote. However, if not carefully considered and structured, they can also be pitfalls for ensuring fair market value and commercially reasonable compensation. Compensation that is not fair market value and/or not commercially reasonable is a potential regulatory red flag and may give rise to significant liability for both corporate and individual actors.

5. THE REGULATORY ENFORCEMENT MINEFIELD

Hospitals face a paradox: on the one hand, government policies are encouraging new activities to promote quality and cost-effectiveness in healthcare delivery, including new provider compensation and incentive models that may incent quality and cost-effectiveness. On the other hand, there is unprecedented and often harsh scrutiny of arrangements between and among healthcare providers, in particular, those that involve compensation or incentives that are out of the ordinary and seem untested.

There was a great deal of attention-getting regulatory enforcement activity in 2015, including a “Fraud Alert” in which the Office of Inspector General of HHS warned that it will take adverse action against physicians when their compensation arrangements are not legally-compliant. There were also a substantial number of lawsuits filed against and/or settled with hospitals and their affiliated physicians and employees under the Federal False Claims Act. Both the volume and settlement amounts of False Claims Act cases involving healthcare providers has been increasing. Where, just a few years ago, Bradford Regional Medical Center made news with a settlement of $2.75 million, in 2015, a hospital settlement exceeded $115 million. Late in 2015, the government released the “Yates Memo,” indicating that, as matter of policy, DOJ will seek to identify individual accountability and culpability when investigating claims of wrongdoing within a corporate organization. The Yates Memo could merely be a restatement of existing policy, and may not actually signal a change in government policy. However, in the current regulatory environment, in which transactional structure and compensation are focal points for scrutiny, the timing of the Yates Memo raises questions about the stakes for individual corporate managers, officers and stakeholders who are involved in complicated transactions.

This being the case, it seems useful to have an understanding of the recent trends in allegations and resolution of enforcement actions against hospitals.

THESE INCLUDE:

- Focus on physician compensation, particularly stacking of compensation that leads to high aggregate compensation amounts;

- Focus on fair market value, including the selection of fair market value benchmarks and the quality of fair market value reports;

- Focus on the accuracy, reliability and completeness of information provided to valuation analysts and other advisors (for example, the number of physicians’ personally performed wRVUs)

- Questioning of commercial reasonableness of compensation arrangements when reasons for the arrangement are not well documented;

- Hospital losses or failure to make a profit construed as evidence of non-fair market value, non-commercially reasonable compensation;

- Tracking of hospital referrals and contribution margins construed as evidence of illegal behavior;

- “Unlikely” whistleblowers, such as physicians and hospital employees who were once stakeholders in a deal; and

- Settlements and liabilities, including legal fees, in staggering amounts.

[1] The authors thank Kelly Anderson, Esq. (Associate General Counsel, Baptist Health, Louisville, KY), Jamie McIntyre, JD. (Manager, HealthCare Appraisers, Inc., Delray Beach, FL), and Robyn Revelson, Esq. (In-House Counsel, Kettering Health Network, Miamisburg, Ohio) for their contributions to this whitepaper.

[2] This whitepaper does not provide and should not be relied on as legal, valuation, business or other professional advice. All opinions and recommendations in this paper are general in nature and not specific to any particular circumstance. Such opinions are personal opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors’ current or former employers or clients.

[3] HHS press release, January 26, 2015